Comets are the big “question marks” of observational astronomy. Some, such as Comet Hyakutake and the Great Daylight Comet of 1910 present themselves seemingly without warning and put on memorable displays. Others, such as the infamous Comet Kohoutek or Comet Elenin, fizzle and fail to perform up to expectations after a much anticipated round of media hype.

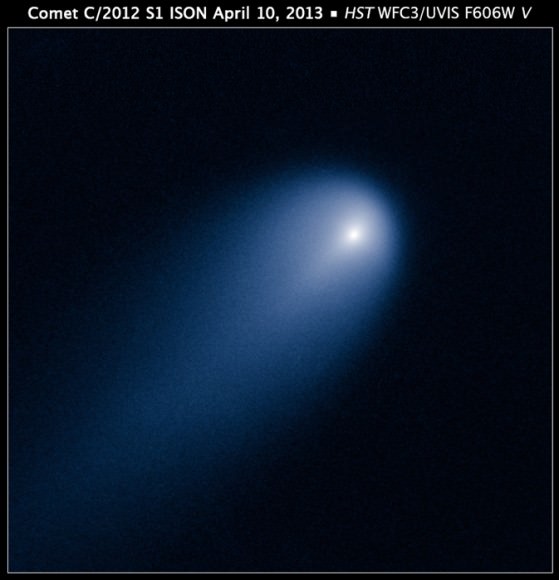

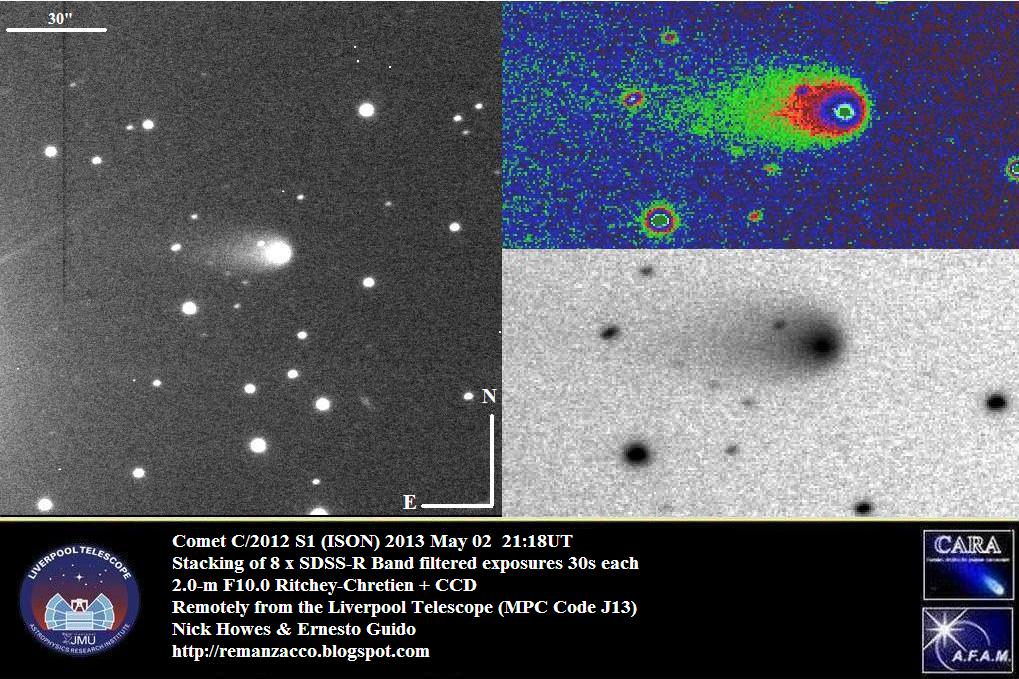

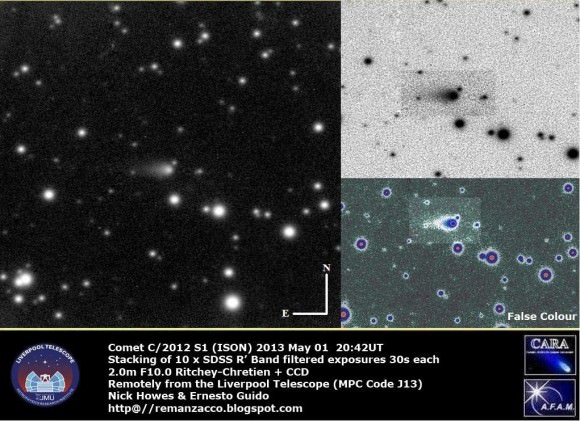

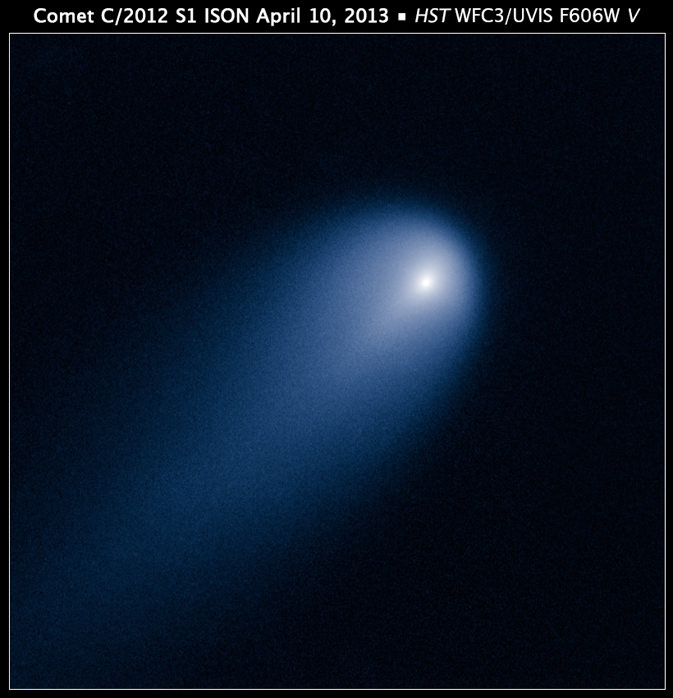

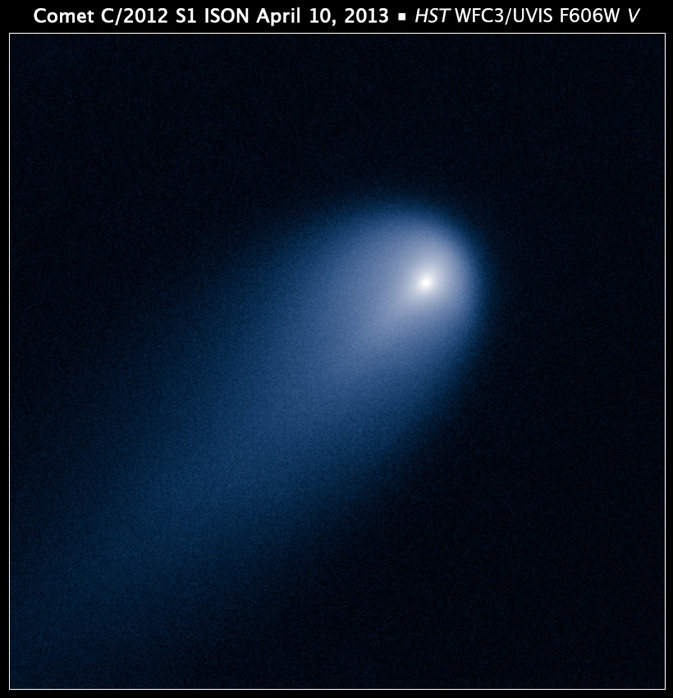

And then there’s the case of Comet C/2012 S1 ISON. Discovered on September 21st, 2012 by Artyom Novichonok and Vitali Nevski while conducting the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) survey, Comet ISON has captivated public interest. The media loves a good comet, or at least the promise of one.

But will Comet ISON perform up to expectations? Recently, veteran comet hunter and observer John Bortle weighed in on a Sky & Telescope post and an email interview with Universe Today on what we might expect to see this fall.

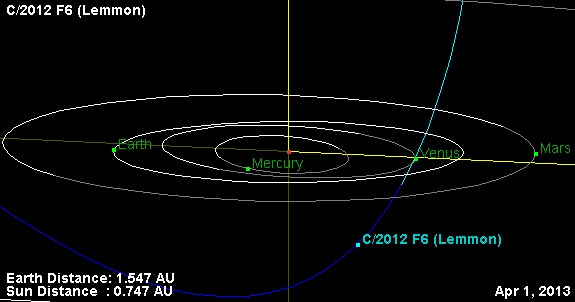

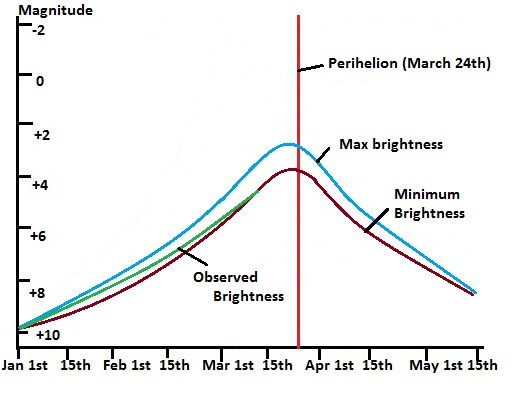

Dozens of comets are discovered every year. Most amount to nothing – a handful, like this year’s comet 2011 L4 PanSTARRS or 2012 F6 Lemmon, may become interesting binocular objects.

Part of what alerted astronomers that Comet ISON may become something special was its extreme discovery distance of 6.7 astronomical units (A.U.s) meaning it should be an intrinsically bright object, coupled with its close approach of 0.012 A.U.s (1.1 million kilometres, accounting for the solar radius) from the surface of the Sun at perihelion.

Universe Today recently caught up with Mr. Bortle, who had the following to say above tentative prospects for Comet ISON in late 2013:

“Comets coming into the near-solar neighborhood from the Oort Cloud for the very first time tend to behave rather differently from most of their other icy brethren. They often will show considerable early activity while still far from the Sun, giving a false sense of their significance. Only when they have ventured to within about 1.5-2.0 astronomical units of the Sun do they begin to reveal their true intrinsic nature in the way of brightness and development. When discovered far from the Sun, this situation has misled astronomers time and again into announcing that a grandiose display is in the offing, only to have the comet ultimately turn out to be a general disappointment. There have been exception to this, but they are rare indeed.”

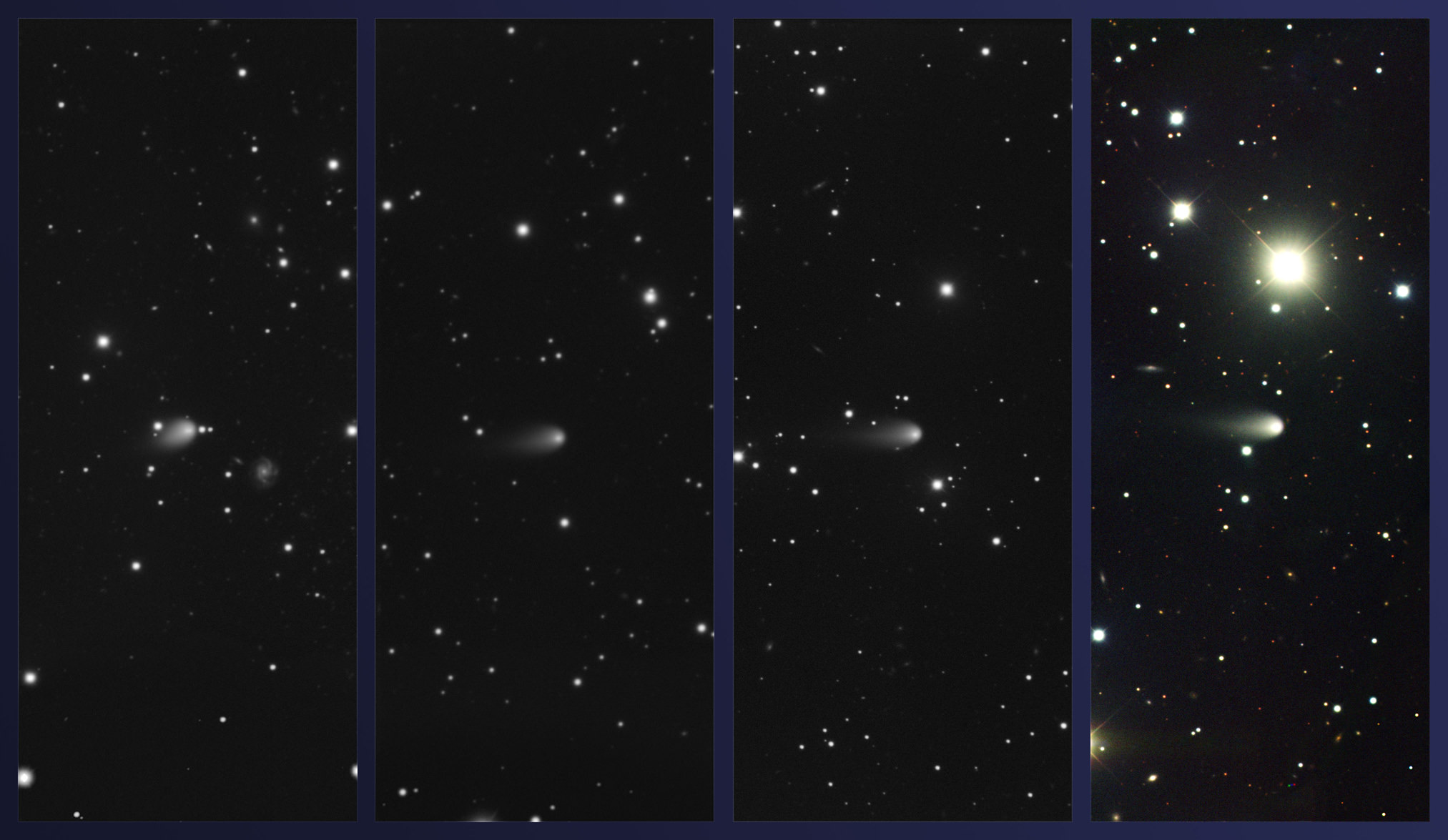

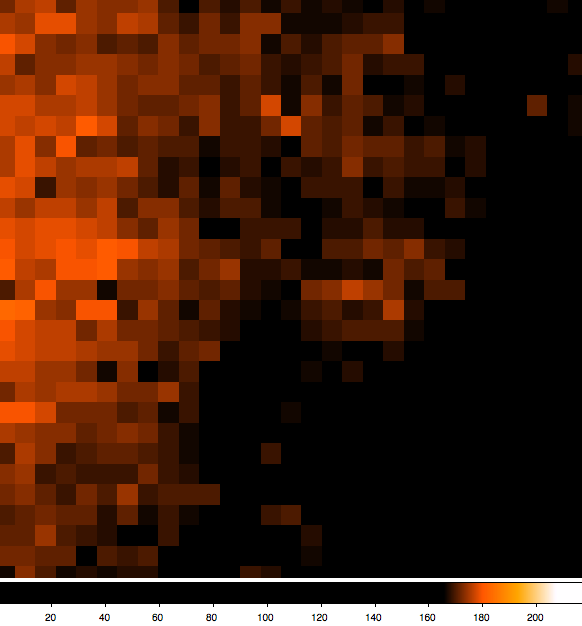

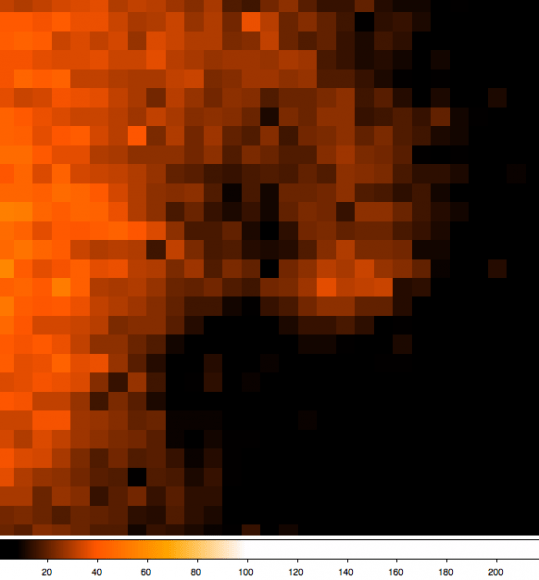

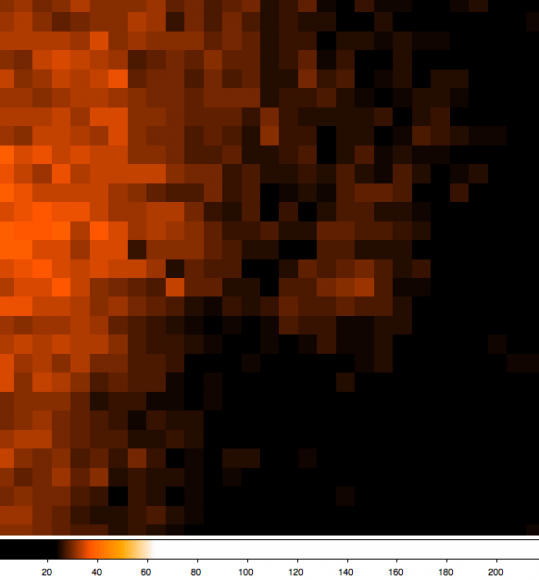

Comet ISON bears similar characteristics to many of the great sungrazing comets of the past. In the last few months, word has made rounds that Comet ISON may be underperforming, stagnating around magnitude +16 (10,000 times fainter than naked eye visibility) as it crosses the expanse of the asteroid belt between Jupiter and Mars.

Bortle, however, cautioned against writing off ISON just yet in a recent message board post. “With this comet’s exceedingly small perihelion distance, the ultimate situation is less clear.” He also continues to note that the prospects for ISON are “really difficult to predict at the moment,” but estimates that Comet ISON “will not actually attain naked eye brightness until just a week or two before perihelion passage.”

Regarding naked eye visibility of Comet ISON, Mr. Bortle also told Universe Today:

“In all probability this will not occur until around early to mid-November. It will not become any sort of impressive sight before disappearing into the morning twilight only a couple of weeks thereafter.”

And that’s the big question that may make the difference between a fine binocular comet and the touted “Comet of the Century…” Will this comet survive its perihelion passage on November 28th?

Concerning the comet’s perihelion passage, Mr. Bortle told Universe Today:

“This is currently a matter of some concern to me. Basing my answer on ISON’s apparent brightness when it was last seen before disappearing into the evening twilight recently suggests that it might be close in intrinsic brightness to the survival/non-survival level for such an extremely close encounter with the Sun. We will know much better once we can view ISON again in September.”

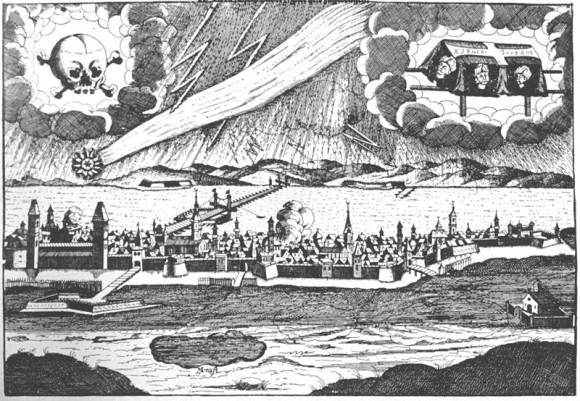

Comet Ikeya-Seki was another sungrazing comet that went on to become a splendid naked eye comet in 1965. The late 1880’s hosted a slew of memorable comets, including two long-tailed sungrazers, one each in 1880 and 1887.

In more recent times, Comet C/2011 W3 Lovejoy survived its December 16th, 2011 perihelion passage 140,000 kilometres from the surface of the Sun to become the surprise hit for southern hemisphere observers.

“IF” comet ISON breaks a negative magnitude, it’ll join the ranks on the top brightest comets since 1935. If it tops -10th magnitude, it’ll best Comet Ikeya-Seki at its maximum in 1965. The magic “brighter than a Full Moon” threshold sits right about at magnitude -12.5, but Bortle cautions that this peak brightness will only persist during the hours surrounding perihelion, when the comet will be very close to the Sun and difficult to see.

Mr. Bortle also voiced a concern to Universe Today that “the initial announcements by professional astronomers concerning ISON’s potential future brightness (“Brighter than the Full Moon”, etc.) were wildly excessive, as was the idea that the comet would be obvious to the general public in the daytime sky as it rounded the Sun in late November. This claim was totally unjustified from the word go.” Mr Bortle also warns that this may be “headed us down the exact same road as the Kohoutek fisaco of 1973/74.”

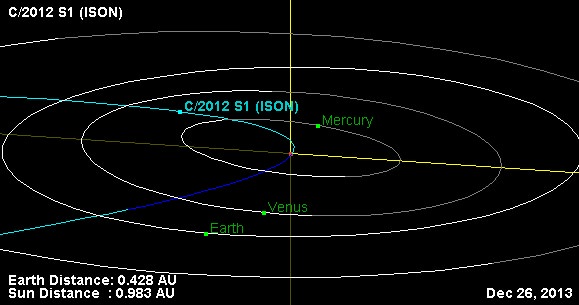

We’re currently losing Comet ISON behind the Sun as it crosses through the constellation Gemini, not return to morning skies until late August. The comet will cross the orbit of Mars in early October and should also cross the +10th magnitude threshold and become visible in binoculars and small telescopes around this date.

From October on in, things should get really interesting. Mr. Bortle predicts that the comet will “develop more slowly in the autumn sky than initially thought,” and won’t become a naked eye object until around November 10th or so. What this sort of lag might do to the internet pundits and prognosticators might be equally interesting to watch.

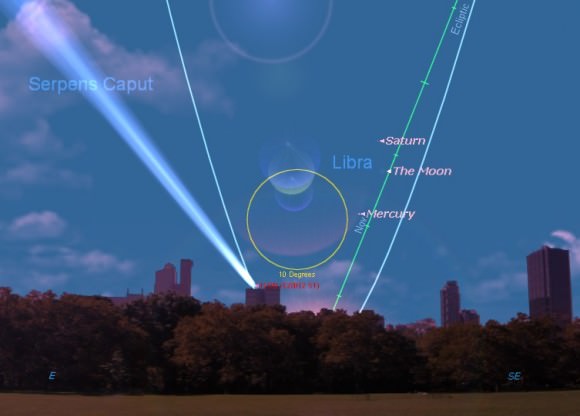

ISON will also track near some interesting morning objects as seen from Earth, including Mars (October 18th), Spica (November 18th), and Mercury & Saturn low in the dawn on November 26th. It will also have another famous comet nearby on November 25th (photo op!) short period Comet 2P Encke.

If Comet ISON survives perihelion, the true show could begin in early December. Comet ISON will re-emerge in the dawn skies, passing a pairing of Mercury and the very old crescent Moon on December 1st. Comet tails are even less predictable than comet magnitudes, but if Comet ISON is to unfurl a long photogenic tail, the weeks leading up to Christmas may be when it does it.

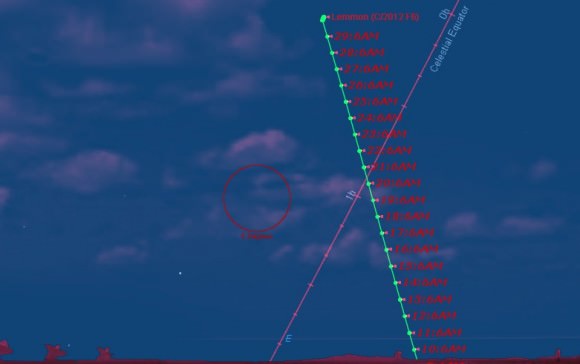

Mr. Bortle predicts a 10 to 15 degree long tail for a post-perihelion ISON as it passes through the constellation Ophiuchus into morning skies. It may become a “headless wonder” similar to the fan-shaped display put on by Comet 2011 L4 PanSTARRS earlier this spring. We’ve even seen models projecting a great fan-shaped dust tail seeming to “loop” around the Sun as seen from our Earthly vantage point!

All interesting conjecture to watch unfold as Comet ISON approaches perihelion this November. Hopefully, the hysteria that follows great cometary apparitions won’t reach a fevered pitch, though we’ve already had to put some early conspiracies to bed surrounding comet ISON.

Will ISON be the “Comet of the Century?” Watch this space… we’ll have more on the play-by-play action as it approaches!

-Read John Bortle’s predictions for Comet ISON in his recent Sky & Telescope post.