[/caption]

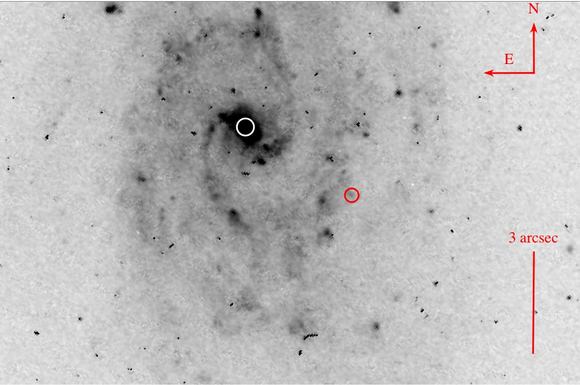

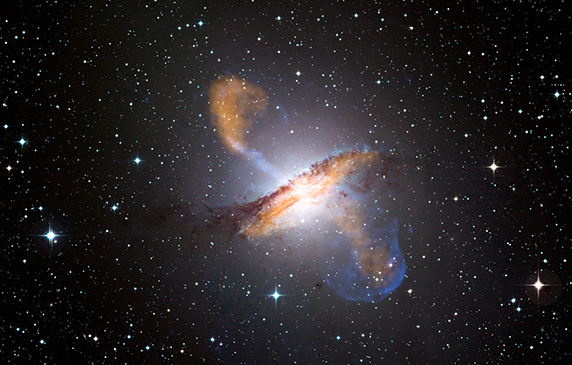

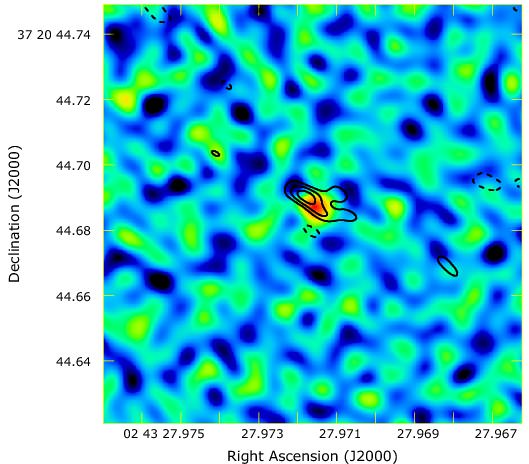

Hanny’s Voorwerp is a popular topic of conversation due to its novel discovery by Hanny Van Arkel perusing images from the Galaxy Zoo project. The tale has become so well known, it was made into a comic book (view here as .pdf, 35MB). But another aspect of the story is how enigmatic the object is. Objects that are so green are rare and it lacked a direct power source to energize it. It was eventually realized a quasar in the neighboring galaxy, IC 2497 could supply the necessary energy. Yet images of the galaxy couldn’t confirm a sufficiently energetic quasar. A new paper discusses what may have happened to the source.

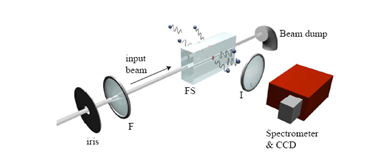

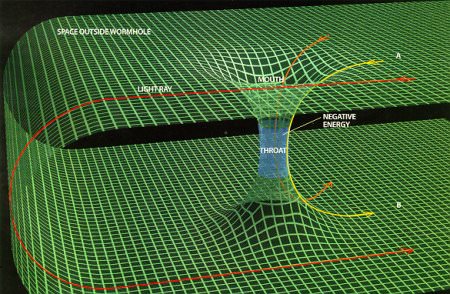

The evidence that a quasar must be involved comes from the green color of the voorwerp itself. Spectra of the object has shown that this coloration is due to a strong level of ionized oxygen, specifically the λ5007 line of O III. While other scenarios could account for this feature alone, the spectra also contained He II emission as well as Ne V and the lines were especially narrow. Should star formation or shockwaves energize the gas, the motions would cause Doppler broadening. An quasar powered Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN) was the best fit.

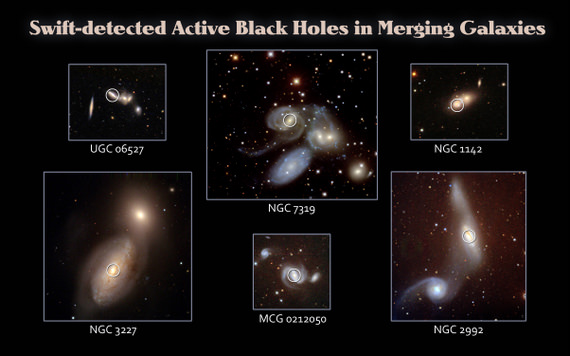

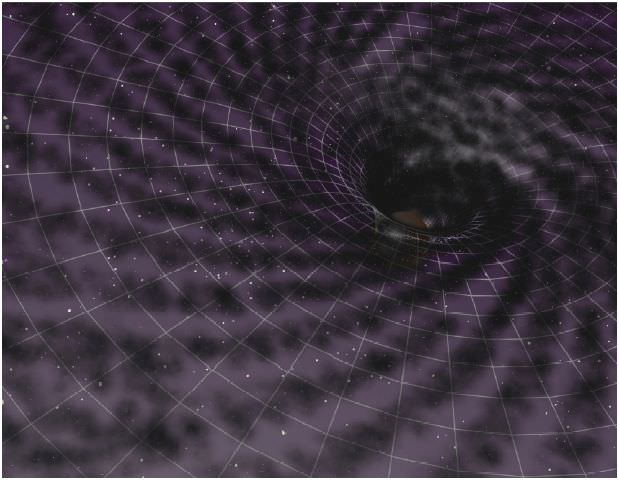

But when telescopes searched for this quasar in the galaxy, it proved elusive. Optical images from WIYN Observatory were unable to resolve the expected point source. Radio observations discovered an object emitting in this range, but far below the amount of energy necessary to power the luminous Voorwerp. Two solutions have been proposed:

“1) the quasar in IC 2497 features a novel geometry of obscuring material and is obscured at an unprecedented level only along our line of sight, while being virtually unobscured towards the Voorwerp; or 2) the quasar in IC 2497 has shut down within the last 70,000 years, while the Voorwerp remains lit up due to the light travel time from the nucleus.”

Recent observations from Suzaku have ruled out the first of these possibilities due to the lack of potassium absorption that would be expected if light from the galaxy were being absorbed in a significant amount. Thus, the conclusion is that the AGN has dropped in total output by at least two orders of magnitude, but more likely by four. In many ways, this is not entirely unexpected since quasars are plentiful in the distant universe where raw material on which to feed was more plentiful. In the present universe, quasars rarely have such material available and can’t maintain it indefinitely.

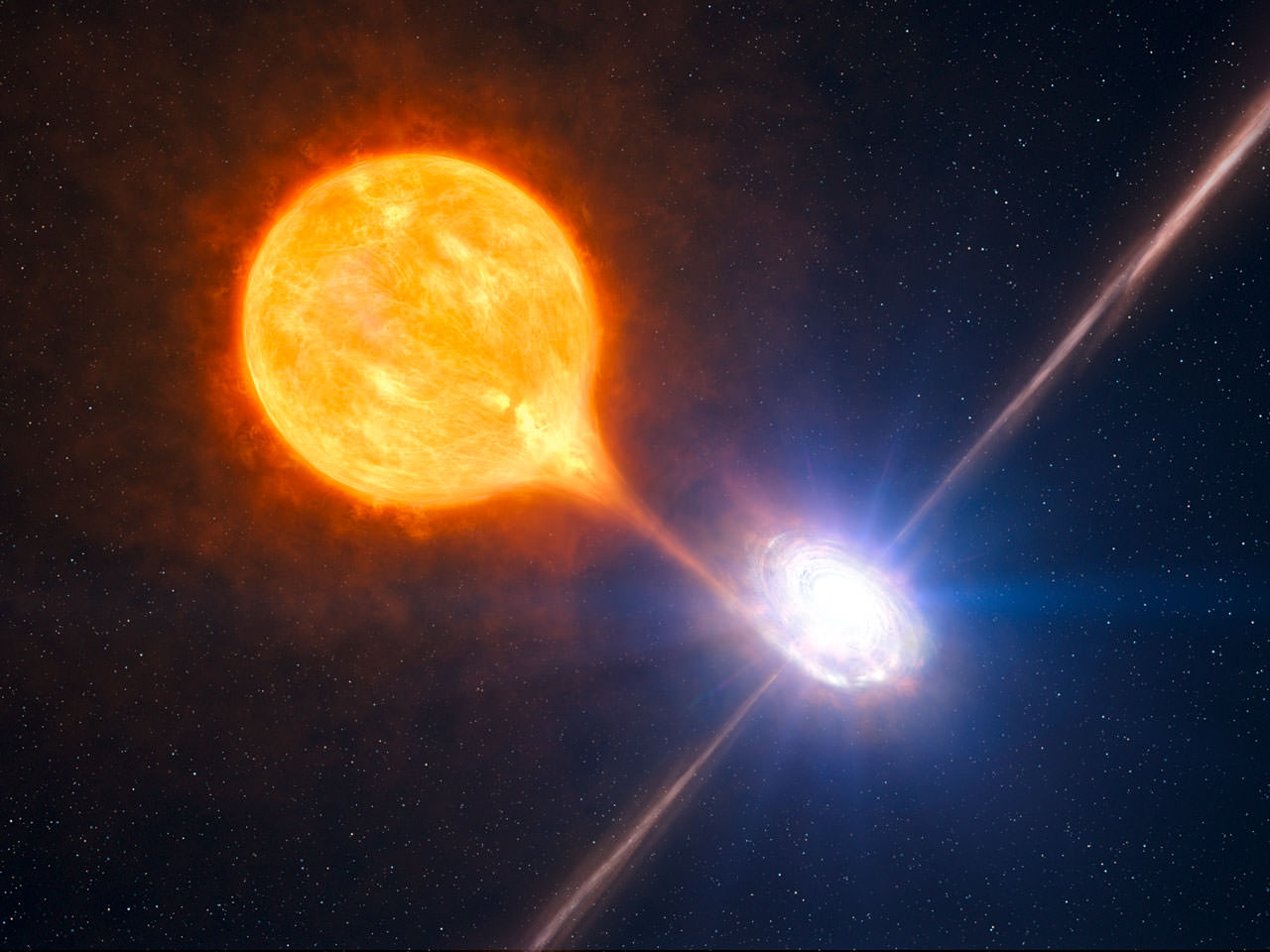

Analogs exist within our own galaxy. X-Ray Binaries (XRBs) are stellar mass black holes which form similar accretion disks and can shut down and excite on short timescales (~1 year). The authors of the new paper attempted to scale up a model XRB system to determine if the timescales would fit with the ~70,000 year upper limit imposed by the travel time. While they found a good agreement with the output from direct accretion itself (10,000–100,000 years) the team found a discrepancy in the disk. In XRBs, the material around the black hole is heated as well, and takes some time to cool down. In this case, the core of the galaxy should still retain a hot disc of material which isn’t present.

This oddity demonstrates that there is still a large amount of knowledge to be gained on the physics surrounding these objects. Fortunately, the relatively close proximity of IC 2497 allows for the potential for detailed followup studies.