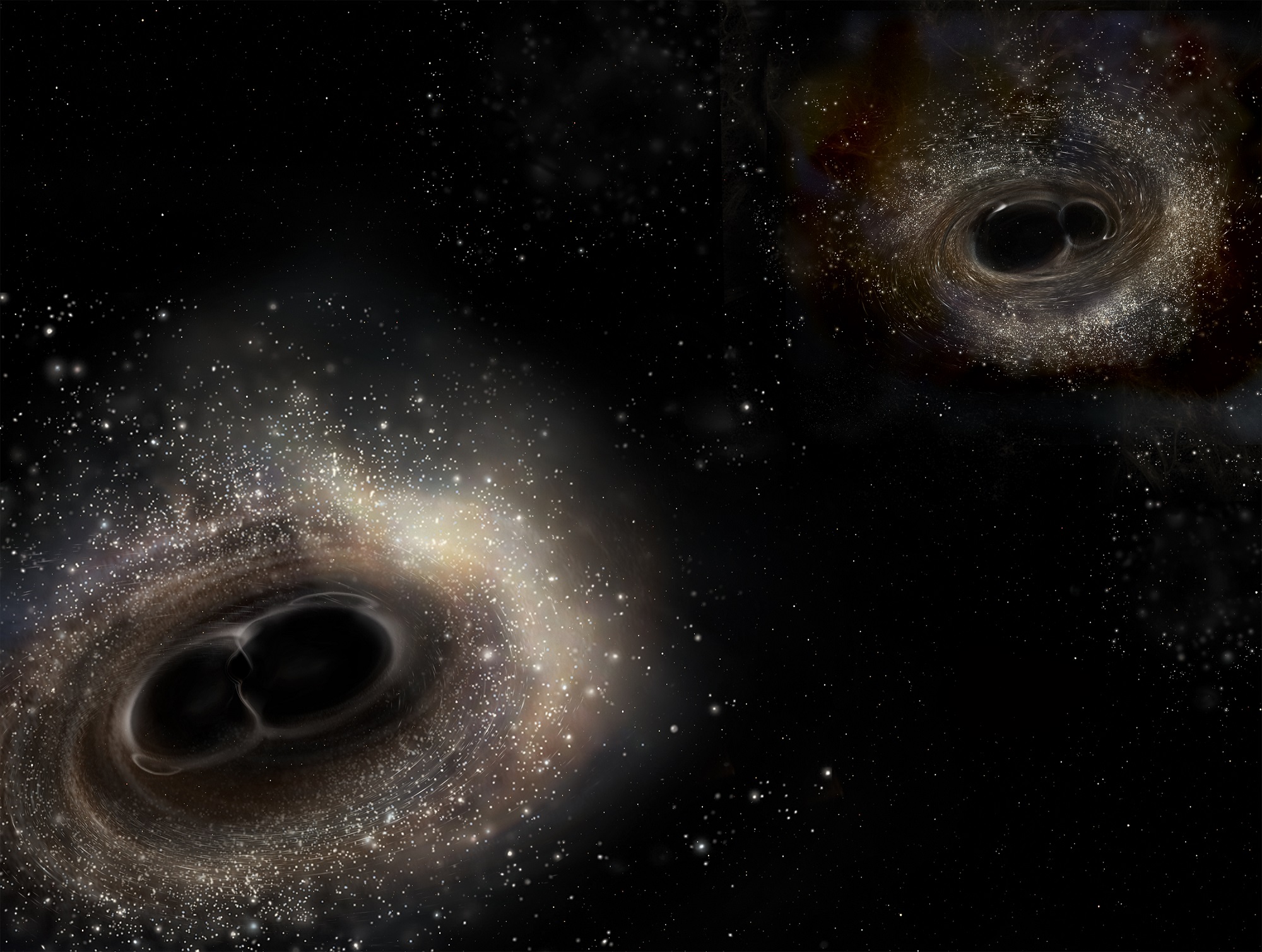

In January of 2016, researchers at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) made history when they announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves. Supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and operated by Caltech and MIT, LIGO is dedicated to studying the waves predicted by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity and caused by black hole mergers.

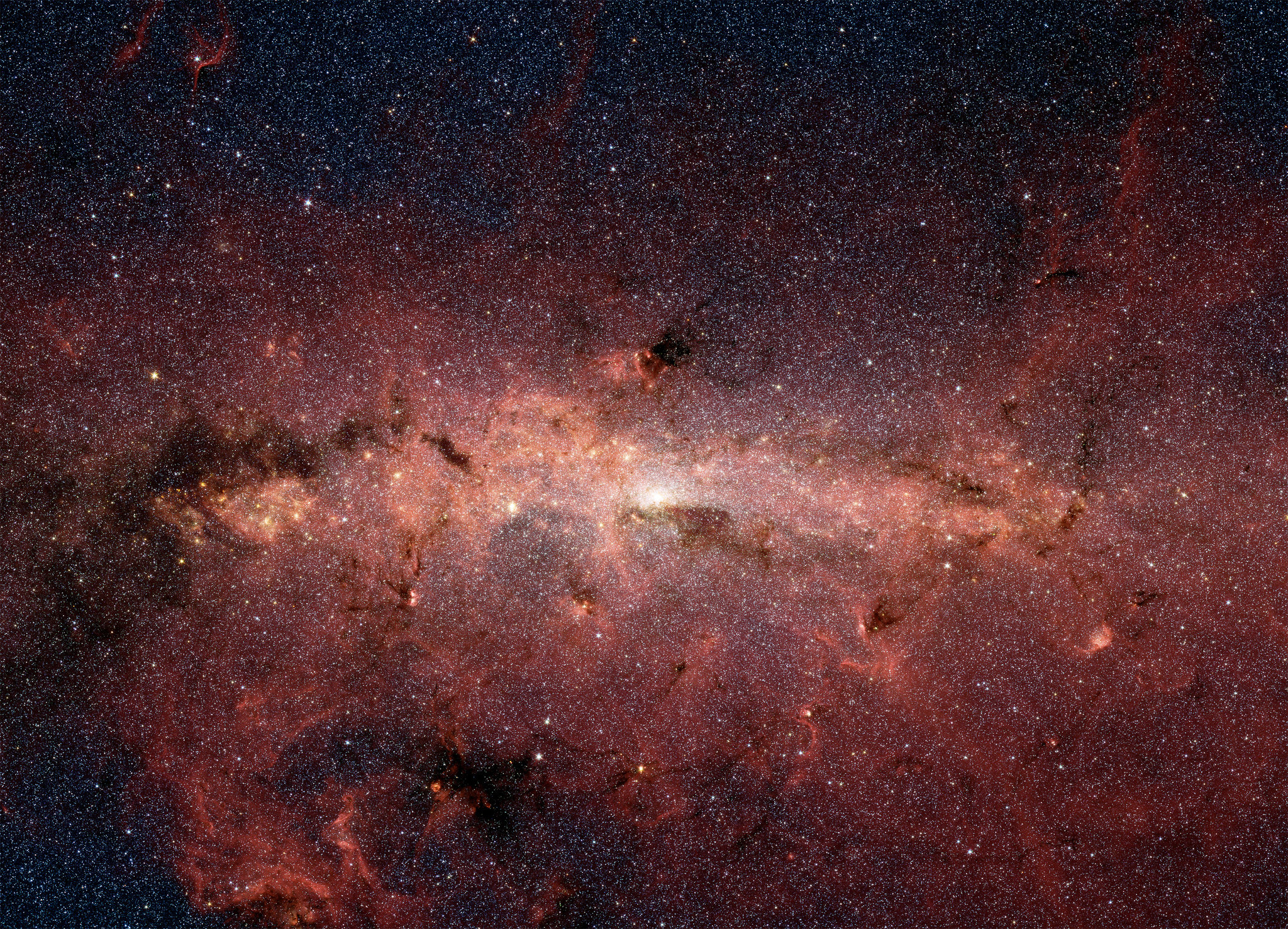

According to a new study by a team of astronomers from the Center of Cosmology at the University of California Irvine, such mergers are far more common than we thought. After conducting a survey of the cosmos intended to calculate and categorize black holes, the UCI team determined that there could be as many as 100 million black holes in the galaxy, a finding which has significant implications for the study of gravitational waves.

The study which details their findings, titled “Counting Black Holes: The Cosmic Stellar Remnant Population and Implications for LIGO“, recently appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Led by Oliver D. Elbert, a postdoc student with the department of Physics and Astronomy at UC Irvine, the team conducted an analysis of gravitational wave signals that have been detected by LIGO.

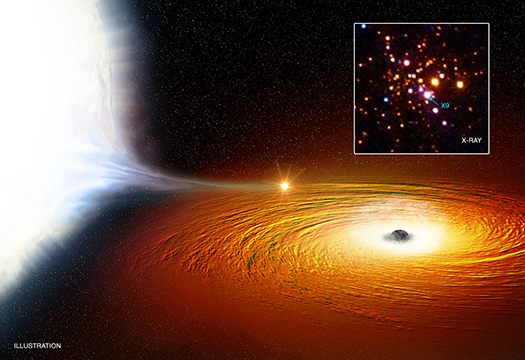

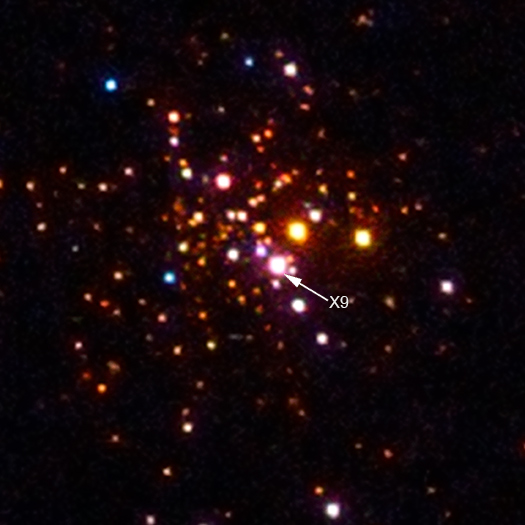

Their study began roughly a year and a half ago, shortly after LIGO announced the first detection of gravitational waves. These waves were created by the merger of two distant black holes, each of which was equivalent in mass to about 30 Suns. As James Bullock, a professor of physics and astronomy at UC Irvine and a co-author on the paper, explained in a UCI press release:

“Fundamentally, the detection of gravitational waves was a huge deal, as it was a confirmation of a key prediction of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. But then we looked closer at the astrophysics of the actual result, a merger of two 30-solar-mass black holes. That was simply astounding and had us asking, ‘How common are black holes of this size, and how often do they merge?’”

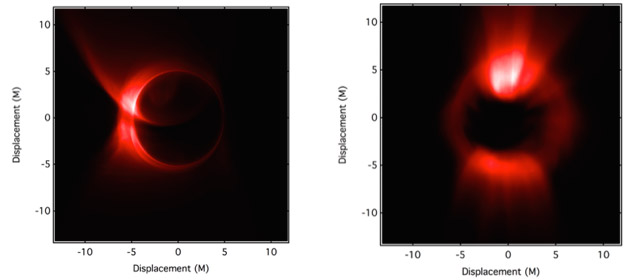

Traditionally, astronomers have been of the opinion that black holes would typically be about the same mass as our Sun. As such, they sought to interpret the multiple gravitational wave detections made by LIGO in terms of what is known about galaxy formation. Beyond this, they also sought to create a framework for predicting future black hole mergers.

From this, they concluded that the Milky Way Galaxy would be home to up to 100 million black holes, 10 millions of which would have an estimated mass of about 30 Solar masses – i.e. similar to those that merged and created the first gravitational waves detected by LIGO in 2016. Meanwhile, dwarf galaxies – like the Draco Dwarf, which orbits at a distance of about 250,000 ly from the center of our galaxy – would host about 100 black holes.

They further determined that today, most low-mass black holes (~10 Solar masses) reside within galaxies of 1 trillion Solar masses (massive galaxies) while massive black holes (~50 Solar masses) reside within galaxies that have about 10 billion Solar masses (i.e. dwarf galaxies). After considering the relationship between galaxy mass and stellar metallicity, they interpreted a galaxy’s black hole count as a function of its stellar mass.

In addition, they also sought to determine how often black holes occur in pairs, how often they merge and how long this would take. Their analysis indicated that only a tiny fraction of black holes would need to be involved in mergers to accommodate what LIGO observed. It also offered predictions that showed how even larger black holes could be merging within the next decade.

As Manoj Kaplinghat, also a UCI professor of physics and astronomy and the second co-author on the study, explained:

“We show that only 0.1 to 1 percent of the black holes formed have to merge to explain what LIGO saw. Of course, the black holes have to get close enough to merge in a reasonable time, which is an open problem… If the current ideas about stellar evolution are right, then our calculations indicate that mergers of even 50-solar-mass black holes will be detected in a few years.”

In other words, our galaxy could be teeming with black holes, and mergers could be happening in a regular basis (relative to cosmological timescales). As such, we can expect that many more gravity wave detections will be possible in the coming years. This should come as no surprise, seeing as how LIGO has made two additional detections since the winter of 2016.

With many more expected to come, astronomers will have many opportunities to study black holes mergers, not to mention the physics that drive them!