[/caption]

Welcome back to the third, and last, installment of Cosmology 101. So far, we’ve covered the history of the universe up to the present moment. But what happens next? How will our universe end? And how can we be so sure that this is how the story unfolded?

Robert Frost once wrote, “Some say the world will end in fire; some say in ice.” Likewise, some scientists have postulated that the universe could die either a dramatic, cataclysmic death – either a “Big Rip” or a “Big Crunch” – or a slower, more gradual “Big Freeze.” The ultimate fate of our cosmos has a lot to do with its shape. If the universe were open, like a saddle, and the energy density of dark energy increased without bound, the expansion rate of the cosmos would eventually become so great that even atoms would be torn apart – a Big Rip. Conversely, if the universe were closed, like a sphere, and gravity’s strength trumped the influence of dark energy, the outward expansion of the cosmos would eventually come to a halt and reverse, collapsing on itself in a Big Crunch.

Despite the poetic beauty of fire, however, current observations favor an icy end to our universe – a Big Freeze. Scientists believe that we live in a spatially flat universe whose expansion is accelerating due to the presence of dark energy; however, the total energy density of the cosmos is most likely less than or equal to the so-called “critical density,” so there will be no Big Rip. Instead, the contents of the universe will eventually drift prohibitively far away from each other and heat and energy exchange will cease. The cosmos will have reached a state of maximum entropy, and no life will be able to survive. Depressing and a bit anti-climactic? Perhaps. But it probably won’t be perceptible until the universe is at least twice its current age.

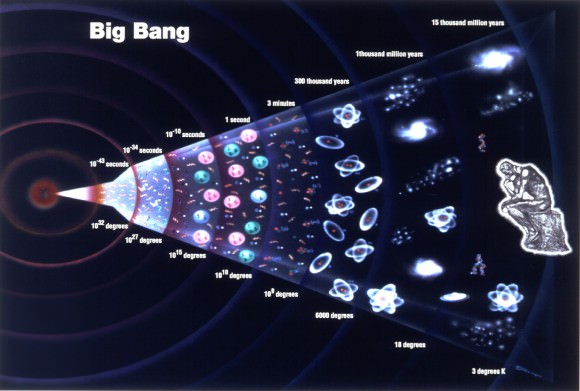

At this point you might be screaming, “How do we know all this? Isn’t it all just rampant speculation?” Well, first of all, we know without a doubt that the universe is expanding. Astronomical observations consistently demonstrate that light from distant stars is always redshifted relative to us; that is, its wavelength has been stretched due to the expansion of the cosmos. This leads to two possibilities when you wind back the clock: either the expanding universe has always existed and is infinite in age, or it began expanding from a smaller version of itself at a specific time in the past and thus has a fixed age. For a long time, proponents of the Steady State Theory endorsed the former explanation. It wasn’t until Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered the cosmic microwave background in 1965 that the big bang theory became the most accepted explanation for the origin of the universe.

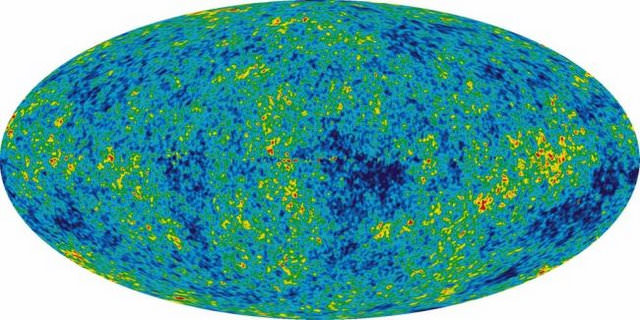

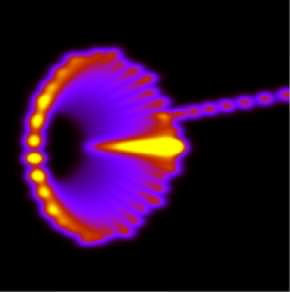

Why? Something as large as our cosmos takes quite a while to cool completely. If the universe did, in fact, began with the kind of blistering energies that the big bang theory predicts, astronomers should still see some leftover heat today. And they do: a uniform 3K glow evenly dispersed at every point in the sky. Not only that – but WMAP and other satellites have observed tiny inhomogeneities in the CMB that precisely match the initial spectrum of quantum fluctuations predicted by the big bang theory.

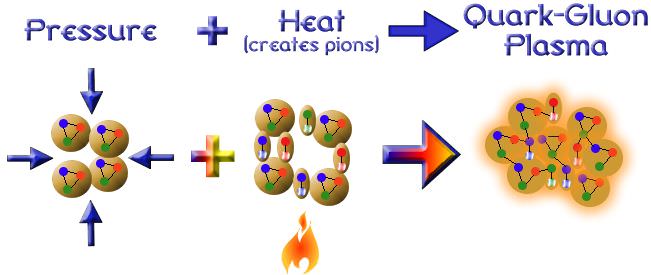

What else? Take a look at the relative abundances of light elements in the universe. Remember that during the first few minutes of the cosmos’ young life, the ambient temperature was high enough for nuclear fusion to occur. The laws of thermodynamics and the relative density of baryons (i.e. protons and neutrons) together determine exactly how much deuterium (heavy hydrogen), helium and lithium could be formed at this time. As it turns out, there is far more helium (25%!) in our current universe than could be created by nucleosynthesis in the center of stars. Meanwhile, a hot early universe – like the one postulated by the big bang theory – gives rise to the exact proportions of light elements that scientists observe in the universe today.

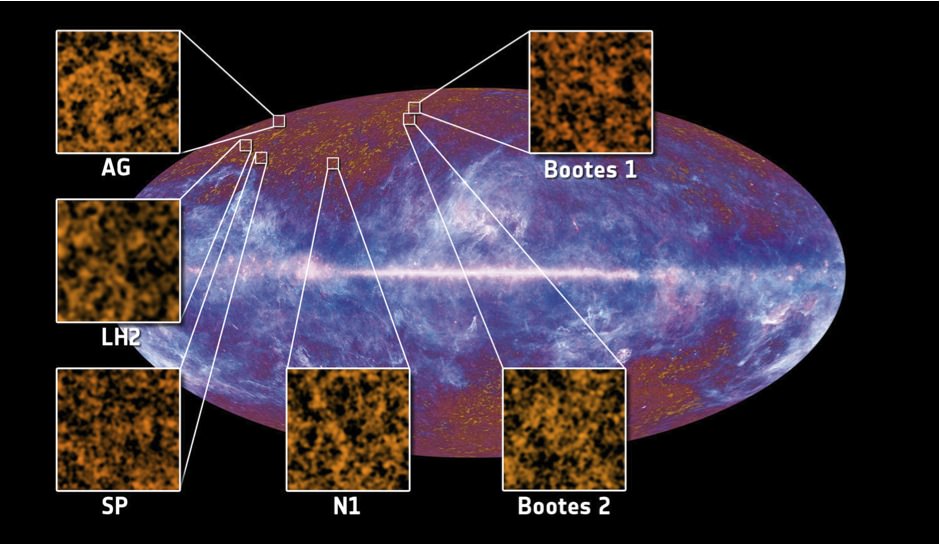

But wait, there’s more. The distribution of large-scale structure in the universe can be mapped extremely well based solely on observed anisotropies in the CMB. Moreover, today’s large-scale structure looks very different from that at high redshift, implying a dynamic and evolving universe. Additionally, the age of the oldest stars appears to be consistent with the age of the cosmos given by the big bang theory. Like any theory, it has its weaknesses – for instance, the horizon problem or the flatness problem or the problems of dark energy and dark matter; but overall, astronomical observations match the predictions of the big bang theory far more closely than any rival idea. Until that changes, it seems as though the big bang theory is here to stay.