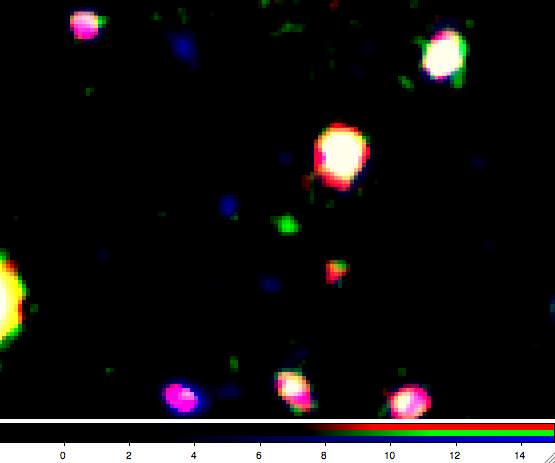

Hubble mosaic of massive galaxy cluster MACS J0717.5+3745, thought to be connected by a filament of dark matter. Credit: NASA, ESA, Harald Ebeling (University of Hawaii at Manoa) & Jean-Paul Kneib (LAM)

Even though teams of scientists around the world are at this very moment hot on the trail of dark matter — the “other stuff” that the Universe is made of and supposedly accounts for nearly 80% of the mass that we can’t directly observe (yet) — and trying to quantify exactly how so-called “dark energy” drives its ever-accelerating expansion, perhaps one answer to these ongoing mysteries is maybe they don’t exist at all.

This is precisely what one astronomer is suggesting in a recent paper, submitted Dec. 3 to Astrophysical Journal Letters.

In a paper titled “An expanding universe without dark matter and dark energy” (arXiv:1212.1110) Pierre Magain, a professor at Belgium’s Institut d’Astrophysique et de Géophysique, proposes that the expansion of the Universe could be explained without the need for enigmatic material and energy that, to date, has yet to be directly measured.

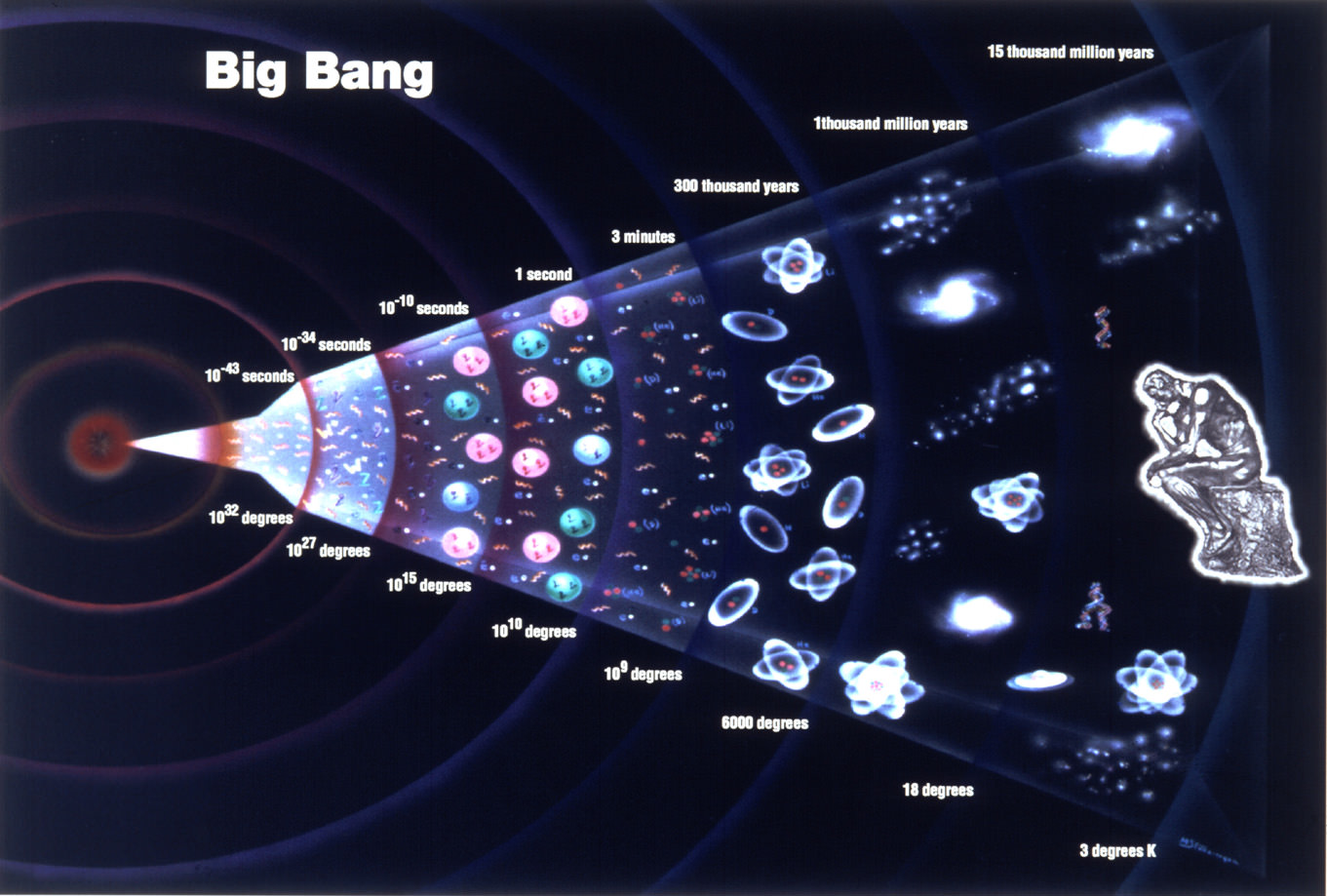

In addition, Magain’s proposal puts a higher age to the Universe than what’s currently accepted. With a model that shows a slower expansion rate during the early Universe than today, Magain’s calculations estimate its age to be closer to 15.4 – 16.5 billion years old, adding a couple billion more candles to the cosmic birthday cake.

In addition, Magain’s proposal puts a higher age to the Universe than what’s currently accepted. With a model that shows a slower expansion rate during the early Universe than today, Magain’s calculations estimate its age to be closer to 15.4 – 16.5 billion years old, adding a couple billion more candles to the cosmic birthday cake.

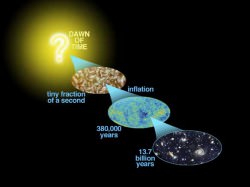

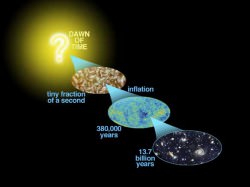

The benefit to a slightly older Universe, Magain posits, is that it’s not so uncannily close to the apparent age of the most distant galaxies recently found — such as MACS0647-JD, which is 13.3 billion light-years away and thus (based on current estimates, see graphic at right) must have formed when the Universe was a mere 420 million years old.

Read more: Now Even Further: Ancient Galaxy is Latest Candidate for Most Distant

Using accepted physics of how time behaves based on Einstein’s theory of general relativity — namely, how the passage of time is relative to the position and velocity of the viewer (as well as the intensity of the gravitational field the viewer is within) — Magain’s model allows for an observer located within the Universe to potentially be experiencing a different rate of time than a hypothetical viewer located outside the Universe. Not to be so metaphysical as to presume that there are external observers of our Universe but merely to say that an external point would be a fixed one against which one could benchmark a varying passage of time inside the Universe, Magain calls this universal relativity.

A viewer experiencing universal relativity would, Magain claims, always measure the curvature of the Universe to be equal to zero. This is what’s currently observed, a “flatness problem” that Magain insinuates is strangely coincidental.

By attributing an expanding Universe to dark energy and the high velocities of stars along the edges of galaxies (as well as the motions of galaxy clusters themselves) to dark matter, we may be introducing ad hoc elements to the Universe, says Magain. Instead, he proposes his “more economical” model — which uses universal relativity — explains these apparently accelerating, increasingly expanding behaviors… and gives a bigger margin of time between the Big Bang and the formation of the first galactic structures.

Read more: First Images in a New Hunt for Dark Energy

There’s quite a bit of math involved, and since I never claimed to understand physics equations you can check out the original paper here.

While intriguing, the bottom line is that dark energy and dark matter have still managed to elude science, existing just outside the borders of what can be observed (although the gravitational lensing effects of what’s thought to be dark matter filaments have been observed by Hubble) and Magain’s paper is merely putting another idea onto the table — one that, while he recognizes needs further testing and relies upon very specific singular parameters, doesn’t depend upon invisible, unobservable and mysteriously dark “stuff”. Whether it belongs on the table or not will be up to other astrophysicists to decide.

While intriguing, the bottom line is that dark energy and dark matter have still managed to elude science, existing just outside the borders of what can be observed (although the gravitational lensing effects of what’s thought to be dark matter filaments have been observed by Hubble) and Magain’s paper is merely putting another idea onto the table — one that, while he recognizes needs further testing and relies upon very specific singular parameters, doesn’t depend upon invisible, unobservable and mysteriously dark “stuff”. Whether it belongs on the table or not will be up to other astrophysicists to decide.

Prof. Magain’s research was supported by ESA and the Belgian Science Policy Office.

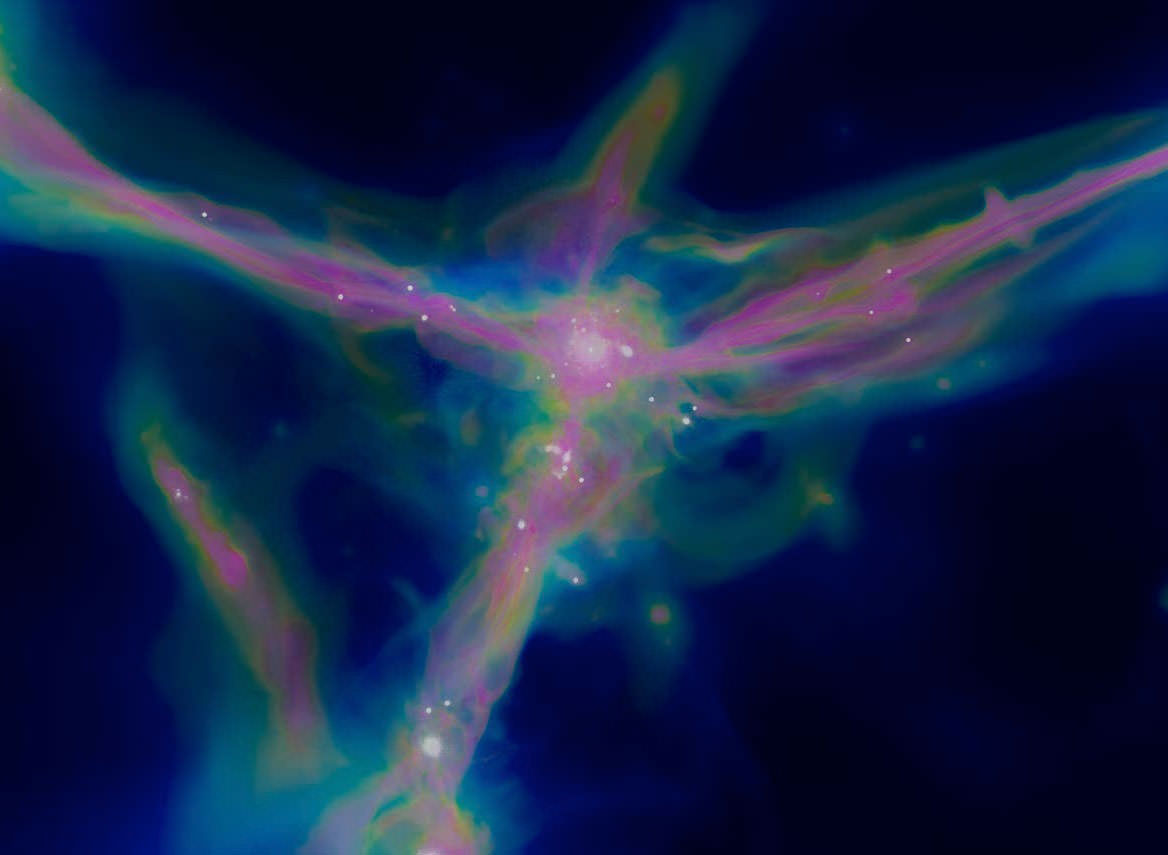

At right: Artist’s impression of dark matter (h/t to Steve Nerlich)

Note: this is “just” a submitted paper and has not been selected for publication yet. Any hypotheses proposed are those of the author and are not endorsed by this site. (Personally I like dark matter. It’s fascinating stuff… even if we can’t see it. Want an astrophysicist’s viewpoint on the existence of dark matter? Check out Ethan Siegel’s blog response here.)