Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! It’s another lunatic weekend as we start off with Regulus and Selene making a close pairing in the Friday evening sky. Why not take a break from difficult galaxy studies and try your hand at some very cool variable stars and multiple systems? It’s time to get out your telescopes and binoculars, pick off a few lunar challenge craters and just kick back and enjoy because… Here’s what’s up!

Friday, June 26, 2009 – Happy Birthday, Charles Messier! Born in 1730 on this date, almost everyone recognizes the name of this French astronomer who discovered 15 comets. He was the first to compile a systematic catalog—the ‘‘M objects.’’ The Messier Catalogue (1784) contains 103 star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies. But did you know Lyman Spitzer, Jr, shared this birthday? Born in 1914, Spitzer advanced our knowledge of physical processes in interstellar space and pioneered efforts to harness nuclear fusion as a clean energy source. He studied star-forming regions and suggested that the brightest stars in spiral galaxies formed recently. Not only that, but Spitzer was the first person to propose placing a large telescope in space, and so launched the development of the Hubble Space Telescope!

Friday, June 26, 2009 – Happy Birthday, Charles Messier! Born in 1730 on this date, almost everyone recognizes the name of this French astronomer who discovered 15 comets. He was the first to compile a systematic catalog—the ‘‘M objects.’’ The Messier Catalogue (1784) contains 103 star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies. But did you know Lyman Spitzer, Jr, shared this birthday? Born in 1914, Spitzer advanced our knowledge of physical processes in interstellar space and pioneered efforts to harness nuclear fusion as a clean energy source. He studied star-forming regions and suggested that the brightest stars in spiral galaxies formed recently. Not only that, but Spitzer was the first person to propose placing a large telescope in space, and so launched the development of the Hubble Space Telescope!

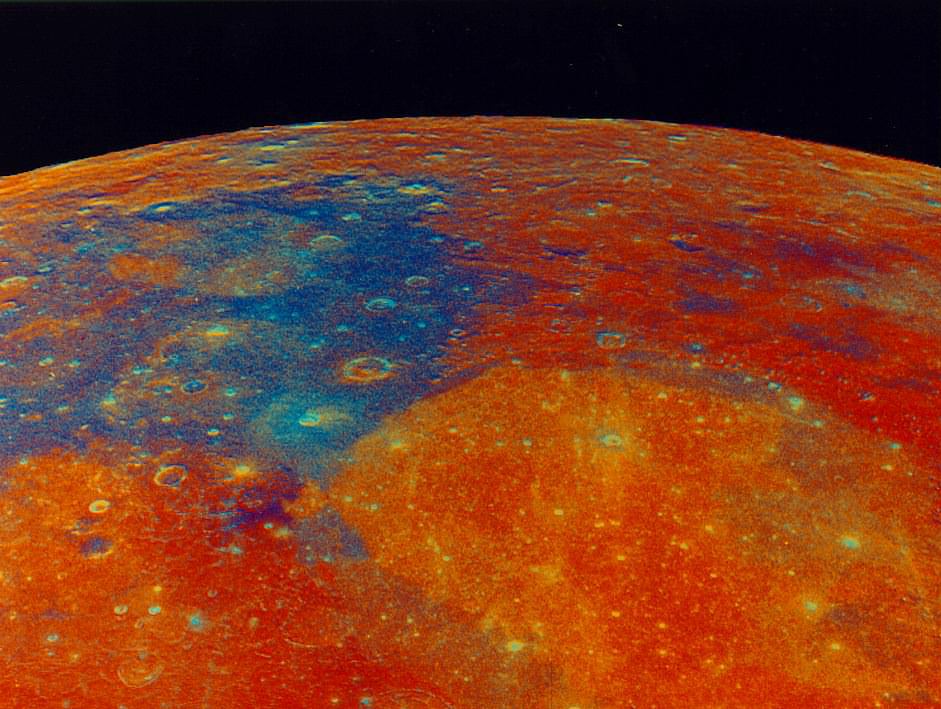

Tonight the mighty Regulus will be very close to the Moon, providing a wonderful opportunity for stargazers. Why not grab a telescope and view the lunar surface for a couple of telescopic challenges that are easy to catch? All you have to know is Mare Crisium!

On the southeastern shoreline is a peninsula that reaches into Crisium’s dark basin. This is Promontorium Agarum. On the western shore, bright Proclus lights the banks, but look into the interior for the two dark pockmarks of Pierce to the north and Picard to the south. Be sure to mark them on your notes!

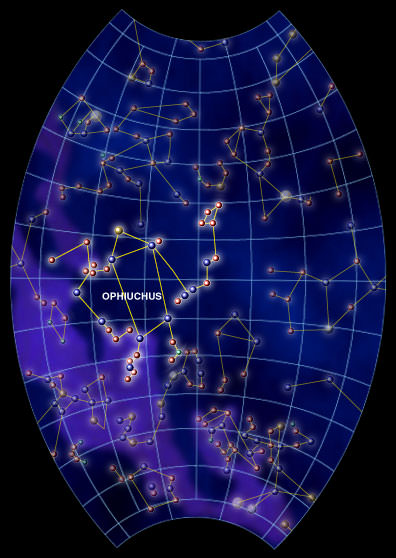

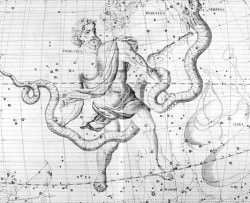

When you’re finished, point your binoculars or telescopes back toward Corona Borealis and about three finger-widths northwest of Alpha for variable star R (RA 15 48 35 Dec +28 09 24). This star is a total enigma. Discovered in 1795, most of the time R carries a magnitude near 6 but can drop to magnitude 14 in a matter of weeks—only to unexpectedly brighten again! It is believed that R emits a carbon cloud, which blocks its light. Oddly enough, scientists can’t even accurately determine the distance to this star! When studied at minimum, the light curve resembles a ‘‘reverse nova’’ and has a peculiar spectrum. It is very possible that this ancient Population II star has used all of its hydrogen fuel and is now fusing helium to form carbon.

Saturday, June 27, 2009 – Tonight we’ll again honor the June 26 birth of Charles Messier by heading toward the lunar surface first, in order to pick off another study object on our list—the twin crater pair Messier and Messier A.

Located in Mare Fecunditatis about a third of its width from west to east, these two craters will be difficult to find in binoculars, but not hard for even a small telescope and intermediate power. Indeed named for the famed French astronomer, the easternmost crater is somewhat oval in shape, with dimensions of 9 by 11 kilometers. At high power, Messier A to the west appears to have overlapped a smaller crater during its formation; and it is slightly larger at 11 by 13 kilometers. Although it is not on the challenge list, you’ll find another point of interest to the northwest. Rima Messier is a long surface crack, which runs diagonally across Mare Fecunditatis’s northwestern flank and reaches a length of 100 kilometers.

For variable star fans, let’s return to and focus our attention on S Coronae Borealis, located just west of Theta and the westernmost star in the constellation’s arc formation (RA 15 21 23 Dec +31 22 02). At magnitude 5.3, this long-term variable takes almost a year to go through its changes—usually far outshining the 7th magnitude star to its northeast—but will drop to a barely visible magnitude14 at minimum. Compare it to the eclipsing binary U Coronae Borealis about a degree northwest. In slightly over 3 days, this Algol-type will range by a full magnitude as its companions draw together.

For variable star fans, let’s return to and focus our attention on S Coronae Borealis, located just west of Theta and the westernmost star in the constellation’s arc formation (RA 15 21 23 Dec +31 22 02). At magnitude 5.3, this long-term variable takes almost a year to go through its changes—usually far outshining the 7th magnitude star to its northeast—but will drop to a barely visible magnitude14 at minimum. Compare it to the eclipsing binary U Coronae Borealis about a degree northwest. In slightly over 3 days, this Algol-type will range by a full magnitude as its companions draw together.

Sunday, June 28, 2009 – As we head out into the night, let’s observe a moment of silence to remember the 1889 passing on this date of Maria Mitchell, the first professional woman astronomer. While pursuing amateur astronomy, she gained fame from her October 1, 1947, observation of a comet, about which she was the first to report. Mitchell was also the first female member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Said Mitchell, ‘‘The eye that directs a needle in the delicate meshes of embroidery will equally well bisect a star with the spider web of the micrometer.’’

Tonight let’s honor Mitchell by locating the lunar crater named in her honor. Begin by visiting the northeast quadrant of the Moon and identify crater Aristoteles. On its eastern edge, you’ll find Mitchell. Measuring only 30 kilometers in diameter, it is dwarfed by Aristoteles’ 87-kilometer diameter, but Maria Mitchell was never dwarfed in life!

To further honor Mitchell, let’s have a look at the 250-light-year-distant silicon star Iota Librae (RA 15 12 13 Dec -19 47 28). This is a challenge for binoculars, but not because the components are so close. In Iota’s case, the near 5th magnitude primary simply overshadows its 9th magnitude companion!

To further honor Mitchell, let’s have a look at the 250-light-year-distant silicon star Iota Librae (RA 15 12 13 Dec -19 47 28). This is a challenge for binoculars, but not because the components are so close. In Iota’s case, the near 5th magnitude primary simply overshadows its 9th magnitude companion!

In 1782, Sir William Herschel measured them and determined they were a true physical pair. Yet, in 1940 Librae A was determined to have an equal-magnitude companion only 0.2’’ away. . .and the secondary was proved to have a companion of its own, which echoes the primary. A four-star system!

Until next week? Keep an eye on the sky for members of the June Draconid meteor shower which peaks Tuesday morning! Wishing you clear skies….

This week’s awesome photos are (in order of appearance): Lyman Spitzer (credit—

courtesy of hubblesite.org), Mare Crisium (credit—Greg Konkel), Mare Fecunditatis and Messier/Messier A (credit—Greg Konkel), S Coronae Borealis (credit—Palomar Observatory, courtesy of Caltech), Aristoteles and Mitchell (credit—Wes Higgins) and Iota Librae (credit—Palomar Observatory, courtesy of Caltech). We thank you so much!