Special thanks to Ninian Boyle astronomyknowhow.com for information in parts of this guide

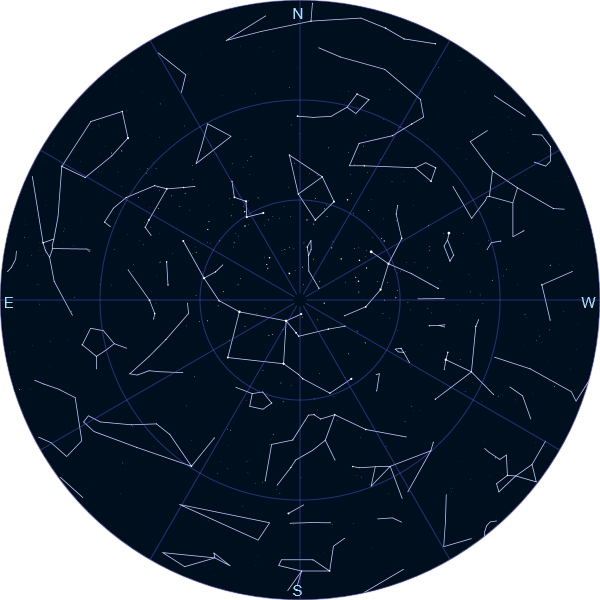

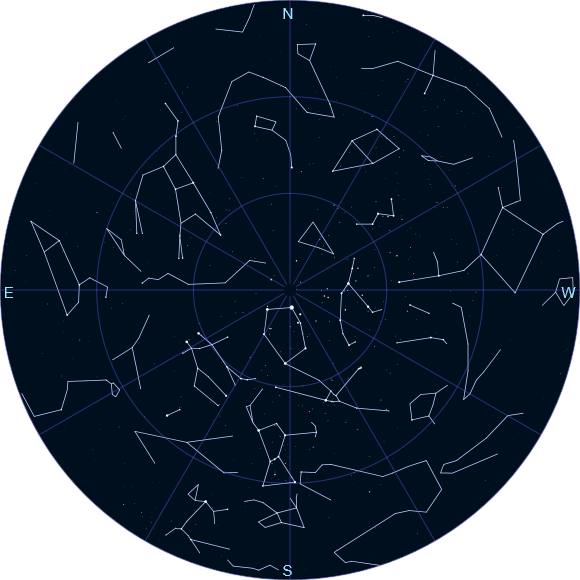

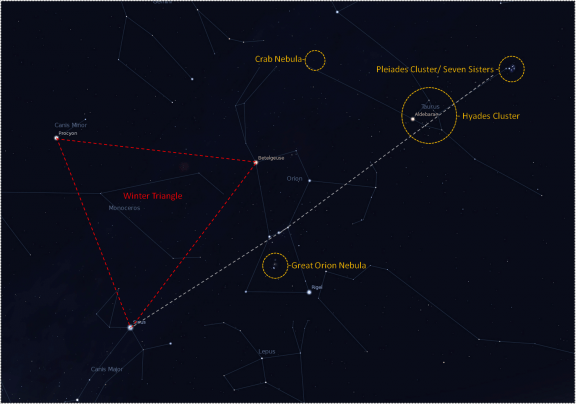

This month, the Solar System gives us a lot to observe and we’ll even start to see the ‘spring’ constellations appear later in the evenings. But February still has the grand constellations of winter, with mighty Orion as a centrepiece to long winter nights.

The Sun has finally started to perform as it should as it approaches “Solar Maximum.” This means we get a chance to see the northern lights (Aurora), especially if you live in such places as Scotland, Canada, Scandinavia, or Alaska or the southern light (Aurora Australis) if you live in the southern latitudes of South America, New Zealand and Australia. Over the past few weeks we have seen some fine aurora displays and will we hope to seesome in February!

We have a bit of a treat in store with a comet being this month’s favourite object with binoculars as well, so please read on to find out more about February’s night sky wonders.

You will only need your eyes to see most of the things in this simple guide, but some objects are best seen through binoculars or a small telescope.

So what sights are there in the February night sky and when and where can we see them?

Aurora

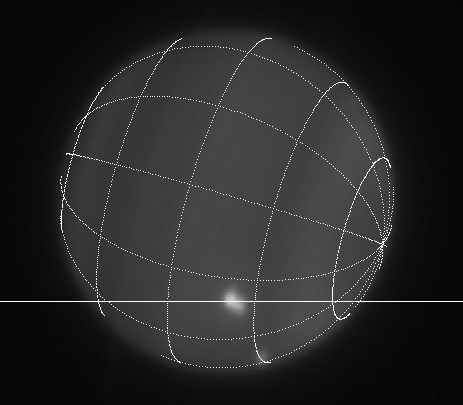

The Aurora or Northern Lights (Aurora Borealis) have been seen from parts of Northern Europe and North America these last few weeks. This is because the Sun has been sending out huge flares of material, some of which have travelled towards us slamming into our magnetic field. The energetic particles then follow the Earth’s magnetic field lines towards the poles and meet the atoms of our atmosphere causing them to fluoresce, similar to what happens in a neon tube or strip light.

The colours of the aurora depend on the type of atom the charged particles strike. Oxygen atoms for example usually glow with a green colour, with some reds, pinks and blues. So the more active the Sun gets, the more likely we are to see the Northern (or Southern) Lights.

All you need to see aurora is your eyes, with no other equipment is needed. Many people image the aurora with exposures of just a few seconds and get fantastic results. Unfortunately auroras are “space weather” and are almost as difficult to predict as normal terrestrial weather, but thankfully we can be given the heads up of potential geomagnetic storms by satellites monitoring the Sun such as “STEREO” (Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory).

Spaceweather.com is a great resource for aurora and other space weather phenomenon and the site has real-time information on current aurora conditions and other phenomenon.

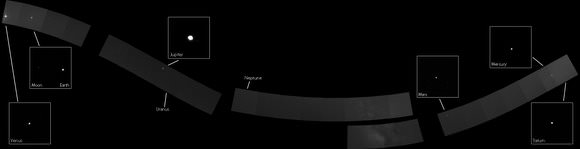

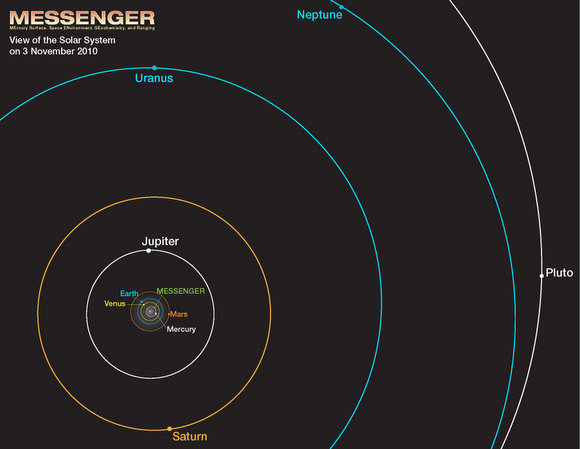

Planets

Mercury is too close to the Sun to be seen at the beginning of the month, but will be visible very low in the south west from the 17th onwards. At the end of February Mercury will be quite bright at around mag -0.8 and will be quite a challenge. It can be seen for about 30 minutes after sunset.

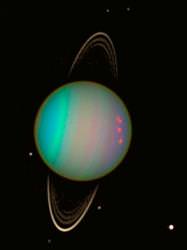

Venus will improve throughout the month in the south west and will pass within half a degree of Uranus on the 9th of February. You can see this through binoculars or a small telescope. On the 25th Venus and the slender crescent Moon can be seen together a fabulous sight. At the end of month Venus closes in on Jupiter for a spectacular encounter in March.

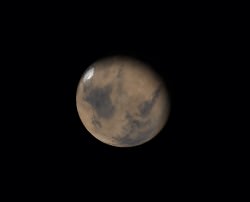

Mars can easily be spotted with the naked eye as a salmon pink coloured “star” and starts off the month in the constellation of Virgo and moves into Leo on the 4th. Mars is at opposition on March 3rd but is also at its furthest from the Sun on the 15th February making this opposition a poor one with respect to observing due to its small apparent size. The planet will still be visually stunning throughout the month.

Jupiter starts off the month high in the south as darkness falls and is still an incredibly bright star-like object. Through good binoculars or a small telescope you can see its four Galilean moons – a fantastic sight. On the 8th at around 19:50 UT, Europa will transit Jupiter and through a telescope you will see the tiny moons shadow move across its surface. Throughout February, Jupiter moves further west for its close encounter with Venus in March.

Saturn rises around midnight in the constellation of Virgo and appears to be a bright yellowish star. Through a small telescope you will see the moon Titan and Saturn’s rings as well.

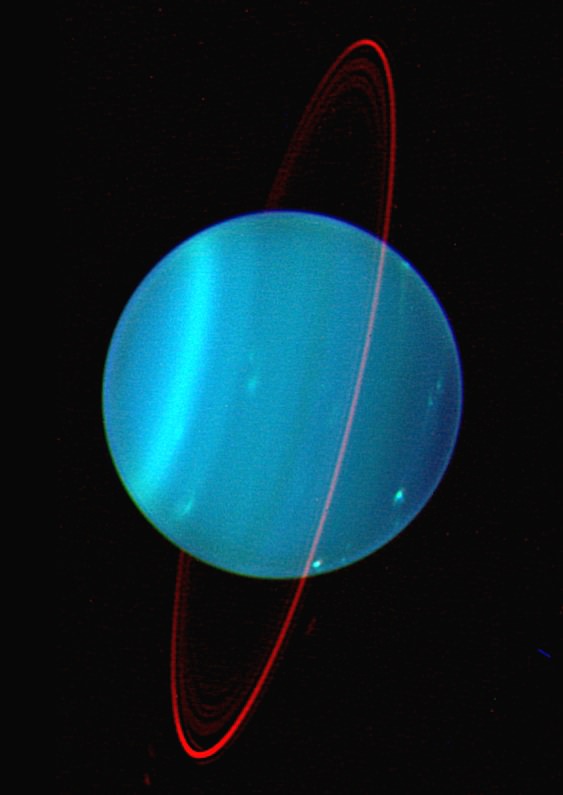

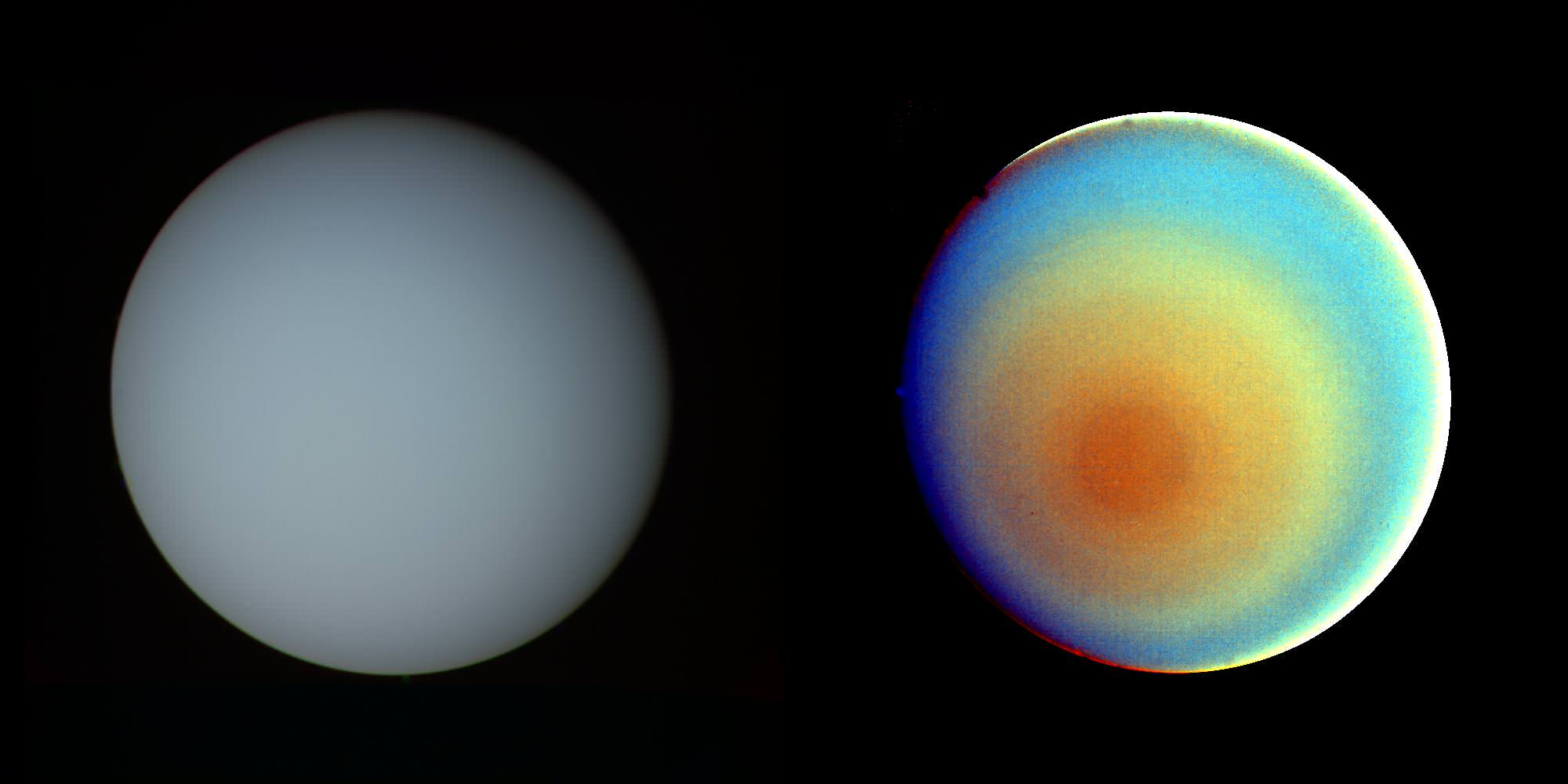

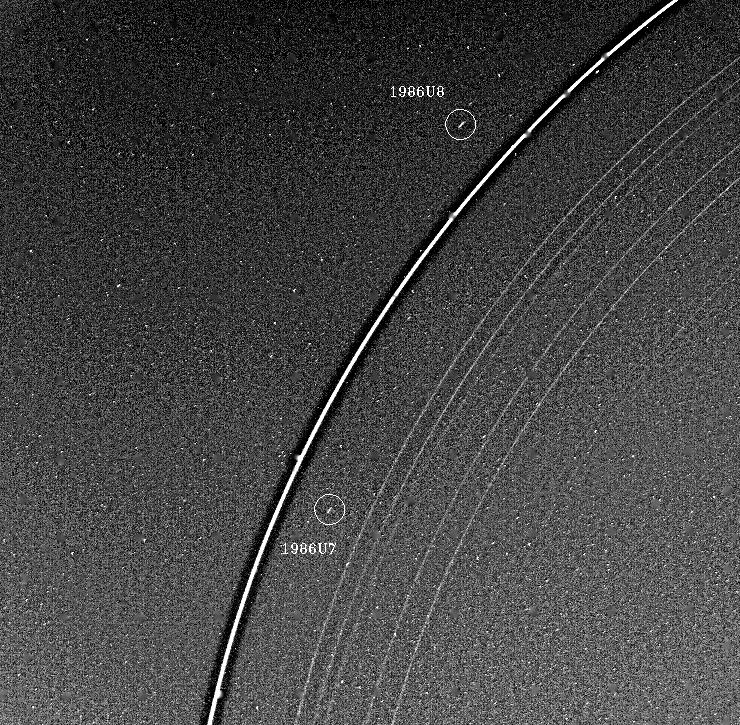

Uranus is now a binocular or telescope object in the constellation of Pisces. On the 9th Uranus and the planet Venus will be within half a degree of each other.

Neptune is not visible this month.

Comets

Comet Garradd is still on show early in the month — if you have binoculars — and as the month progresses the viewing should improve. You can find the comet in the constellation of Hercules not far from the globular cluster M92. It is about a half a degree away or around the same width as the full Moon. The comet is around magnitude 7 or a little fainter than the more famous globular cluster M13 also to be found in Hercules, so you will definitely need binoculars to see it. The comet is heading north over the course of the month which should mean that it will become a little easier to see. At the beginning of the month you will have to get up early to see it, the best time being around 5:30 to 6:30 GMT. By the end of the month though, it should be visible all night long.

Moon phases

- Full Moon – 7th February

- Last Quarter – 14th February

- New Moon – 21st February

Constellations

In February, Orion still dominates the sky but has many interesting constellations surrounding it.

Above and to the left of Orion you will find the constellation of Gemini, dominated by the stars Castor and Pollux, representing the heads of the twins with their bodies moving down in parallel lines of stars with each other.

Legend has it that Castor and Pollux were twins conceived on the same night by the princess Leda. On the night she married the king of Sparta, wicked Zeus (disguised as a swan) invaded the bridal suite, fathering Pollux who was immortal and twin of Castor who was fathered by the king so was mortal.

Castor and Pollux were devoted to each other and Zeus decided to grant Castor immortality and placed Castor with his brother Pollux in the stars.

Gemini has a few deep sky objects such as the famous Eskimo nebula and some are a challenge to see. Get yourself a good map, Planisphere or star atlas and see what other objects you can track down.