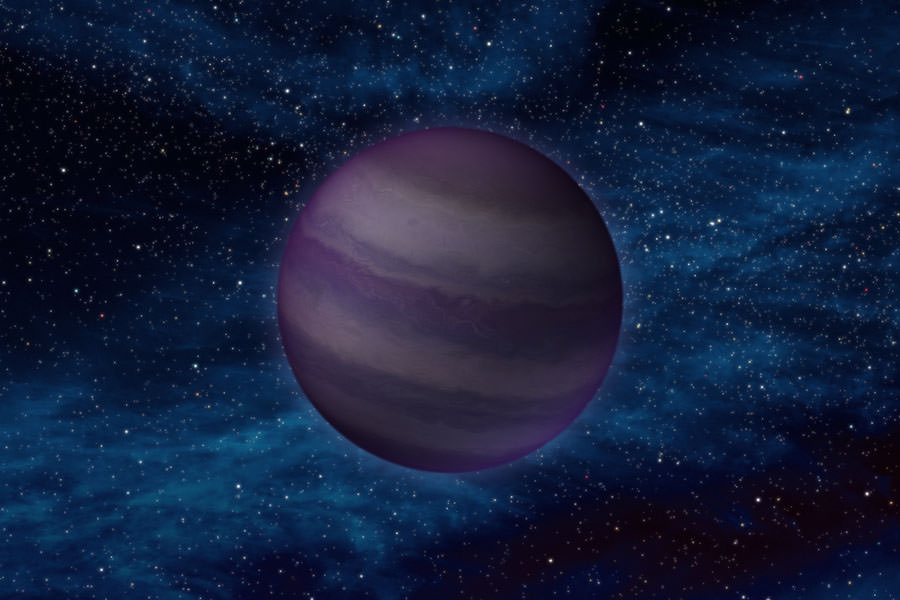

[/caption]What would you say if I told you there are stars with a temperature close to that of a human body? Before you have me committed, there really is such a thing. These “cool” stars belong to the brown dwarf family and are termed Y dwarfs. For over ten years astronomers have been hunting for these dark little beasties with no success. Now infrared data from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) has turned up six of them – and they’re less than 40 light years away!

“WISE scanned the entire sky for these and other objects, and was able to spot their feeble light with its highly sensitive infrared vision,” said Jon Morse, Astrophysics Division director at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “They are 5,000 times brighter at the longer infrared wavelengths WISE observed from space than those observable from the ground.”

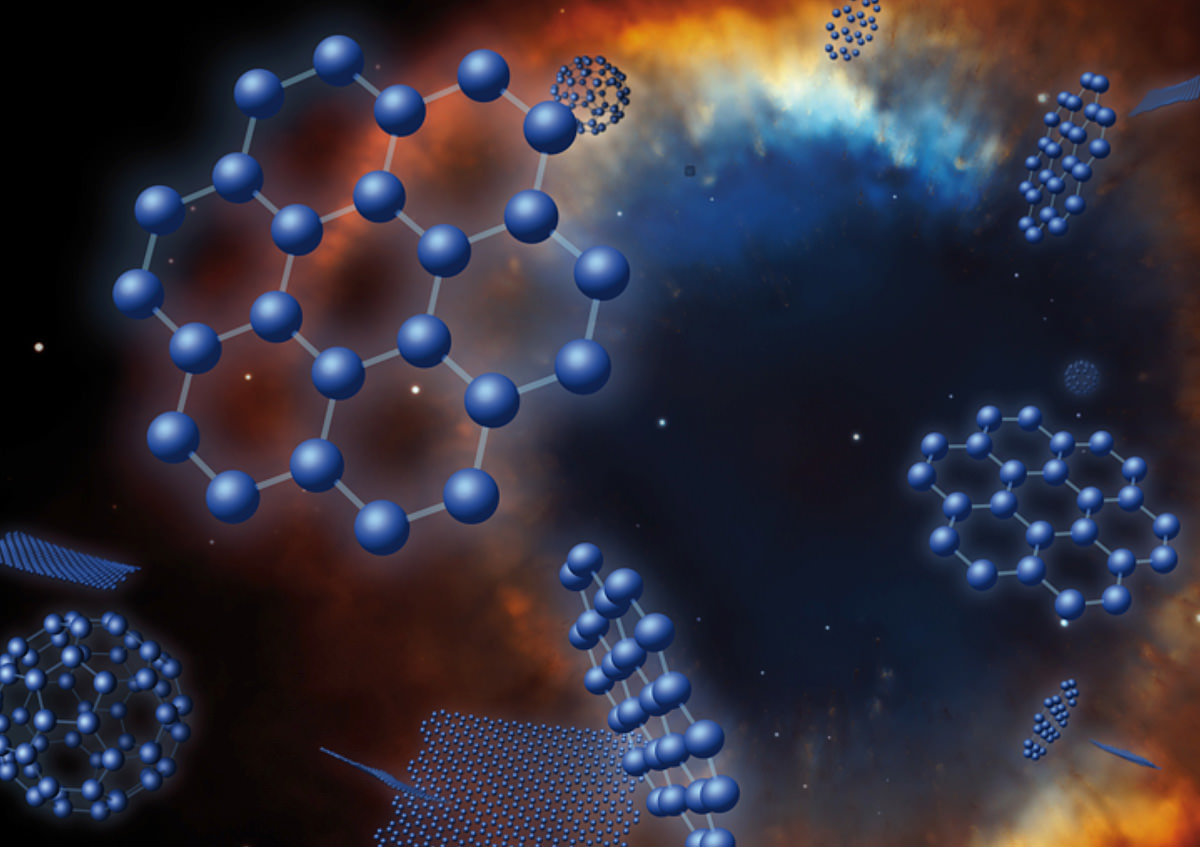

Often referred to as “failed stars”, the Y-class suns are simply too low mass to ignite the fusion process which makes other stars shine in visible light. As they age, they fade away – their only signature is what can be spotted in infrared. The brown dwarfs are of great interest to astronomers because we can gain a better understanding as to stellar natures and how planetary atmospheres form and evolve. Because they are alone in space, it’s much easier to study these Jupiter-like suns… without being blinded by a parent star.

“Brown dwarfs are like planets in some ways, but they are in isolation,” said astronomer Daniel Stern, co-author of the Spitzer paper at JPL. “This makes them exciting for astronomers — they are the perfect laboratories to study bodies with planetary masses.”

The WISE mission has been extremely productive – turning up more than 100 brown dwarf candidates. Scientists are hopeful that even more will emerge as huge amounts of data are processed from the most advanced survey of the sky at infrared wavelengths to date. Just imagine how much information was gathered from January 2010 to February 2011 as the telescope scanned the entire sky about 1.5 times! One of the Y dwarfs, called WISE 1828+2650, is the record holder for the coldest brown dwarf, with an estimated atmospheric temperature cooler than room temperature, or less than about 80 degrees Fahrenheit (25 degrees Celsius).

“The brown dwarfs we were turning up before this discovery were more like the temperature of your oven,” said Davy Kirkpatrick, a WISE science team member at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif. “With the discovery of Y dwarfs, we’ve moved out of the kitchen and into the cooler parts of the house.”

Kirkpatrick is the lead author of a paper appearing in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, describing the 100 confirmed brown dwarfs. Michael Cushing, a WISE team member at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, is lead author of a paper describing the Y dwarfs in the Astrophysical Journal.

“Finding brown dwarfs near our Sun is like discovering there’s a hidden house on your block that you didn’t know about,” Cushing said. “It’s thrilling to me to know we’ve got neighbors out there yet to be discovered. With WISE, we may even find a brown dwarf closer to us than our closest known star.”

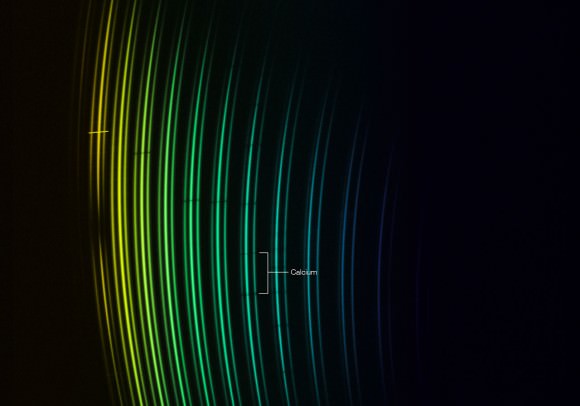

Given the nature of the Y-class stars, positively identifying these special brown dwarfs wasn’t an easy task. For that, the WISE team employed the aid of the Spitzer Space Telescope to refine the hunt. From there the team used the most powerful telescopes on Earth – NASA Infrared Telescope Facility atop Mauna Kea, Hawaii; Caltech’s Palomar Observatory near San Diego; the W.M. Keck Observatory atop Mauna Kea, Hawaii; and the Magellan Telescopes at Las Campanas Observatory, Chile, and others – to look for signs of methane, water and even ammonia. For the very coldest of the new Y dwarfs, the team used NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Their final answer came when changes in spectra indicated a low temperature atmosphere – and a Y-class signature.

“WISE is looking everywhere, so the coolest brown dwarfs are going to pop up all around us,” said Peter Eisenhardt, the WISE project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, and lead author of a recent paper in the Astronomical Journal on the Spitzer discoveries. “We might even find a cool brown dwarf that is closer to us than Proxima Centauri, the closest known star.”

How cool is that?!

Original Story Source: JPL News Release.