[/caption]

Although they only make up about one percent of the interstellar medium, giant molecular clouds are a rather formidable thing. These dense masses of gas can reach tens of parsecs in diameter and we know them as star forming regions. But, what we didn’t know is that light from massive stars can tear them apart.

New findings presented by Dr. Elizabeth Harper-Clark and Prof. Norman Murray of the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics (CITA) show that radiation pressure is not a thing which should be discounted. It has widely been theorized that supernovae accounted for GMC disruption, but “Even before a single star explodes as a supernova, massive stars carve out huge bubbles and limit the star formation rates in galaxies.”

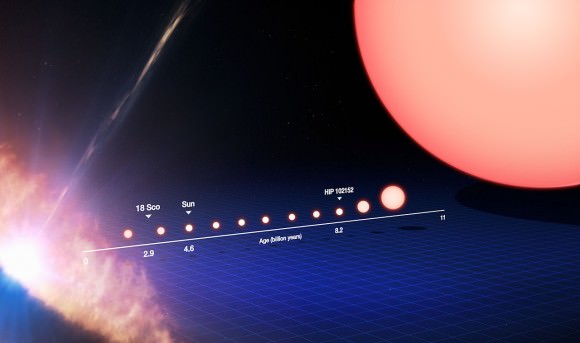

Galaxies harbor stellar nurseries and, as stars are born, the galaxy evolves. It is our understanding that stellar birth occurs within giant molecular clouds where low temperatures, high density and gravity work together to ignite the stellar process. It happens at a smooth and steady rate – a pace which we surmise occurs from the outflow of energy from other stars and possibly black holes. But just what exactly is the life expectancy of a GMC?

To understand a giant molecular cloud is to understand the mass of the stars contained within it. This is key to star formation rates. “In particular, the stars within a GMC can disrupt their host and consequently quench further star formation.” says Harper-Clark. “Indeed, observations show that our own galaxy, the Milky Way, contains GMCs with extensive expanding bubbles but without supernova remnants, indicating that the GMCs are being disrupted before any supernovae occur.”

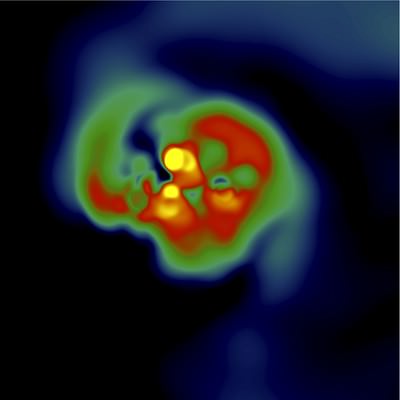

What’s happening here? Ionization and radiation pressure are blending together within the gases. Electrons are being forced out of atoms during ionization… an action which happens incredibly fast, heating up the gases and increasing pressure. The often over-looked radiation is far more subtle. “The momentum from the light is transferred to the gas atoms when light is absorbed.” says the team. “These momentum transfers add up, always pushing away from the light source, and produce the most significant effect, according to these simulations.”

The simulations performed by Harper-Clark are just the beginning of new studies. The work shows calculations of the effects of radiation pressure on GMCs and reveal they are capable of not only disrupting star-forming regions, but completely blowing them apart, cutting off further formation when about 5 to 20% of the clouds mass had been converted to stars. “The results suggest that the slow rate of star formation seen in galaxies across the Universe may be the result of radiative feedback from massive stars,” says Professor Murray, Director of CITA.

So what of supernovae? Incredibly enough, it would seem they are simply unimportant to the equation. By calculating the results both with and without star light radiation, supernova events didn’t change star formation nor did they alter the GMC. “With no radiation feedback, supernovae exploded in a dense region leading to rapid cooling. This robbed the supernovae of their most effective form of feedback, hot gas pressure.” says Dr. Harper-Clark. “When radiative feedback is included, the supernovae explode into an already evacuated (and leaky) bubble, allowing the hot gas to expand rapidly and leak away without affecting the remaining dense GMC gas. These simulations suggest that it is the light from stars that carves out nebulae, rather than the explosions at the end of their lives.”

Original Story Source: Canadian Astronomical Society More information on Dr. Harper-Clark’s work can be found here.