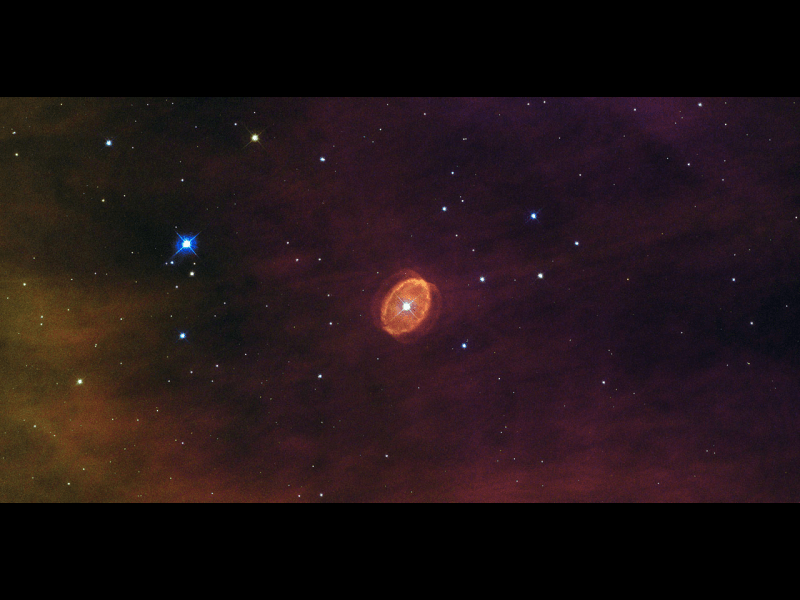

Like millionaires that burn through their cash too quickly, astronomers have found one factor behind why compact elliptical galaxies stopped growing stars about 11 billion years ago: they ate through their gas reserves.

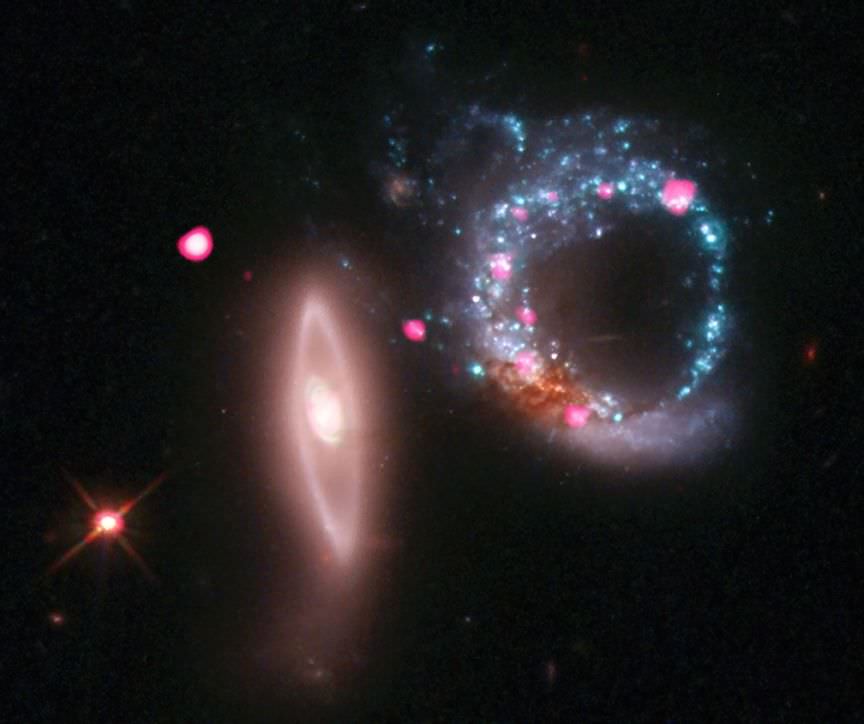

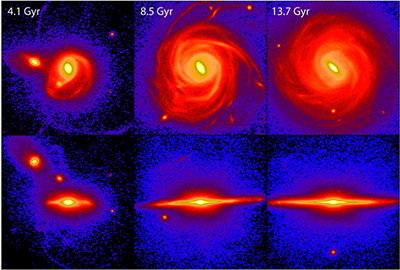

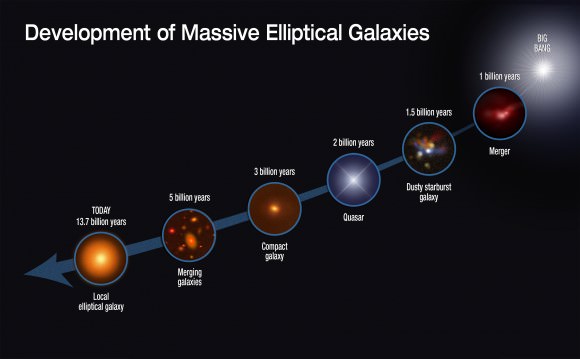

The revelation comes as researchers released a new evolutionary track for compact elliptical galaxies that stopped their star formation when the universe was just three billion years old. When these galaxies ran out of gas, some of them cannibalized smaller galaxies to create giant elliptical galaxies. The “burned-out”galaxies have stars crowding 10 to 100 times more densely than elliptical galaxies formed more recently through a different evolutionary track.

“We at last show how these compact galaxies can form, how it happened, and when it happened. This basically is the missing piece in the understanding of how the most massive galaxies formed, and how they evolved into the giant ellipticals of today,” stated Sune Toft, who led the study and is a researcher at the Dark Cosmology Center at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen.

“This had been a great mystery for many years, because just three billion years after the Big Bang we see that half of the most massive galaxies have already completed their star formation.”

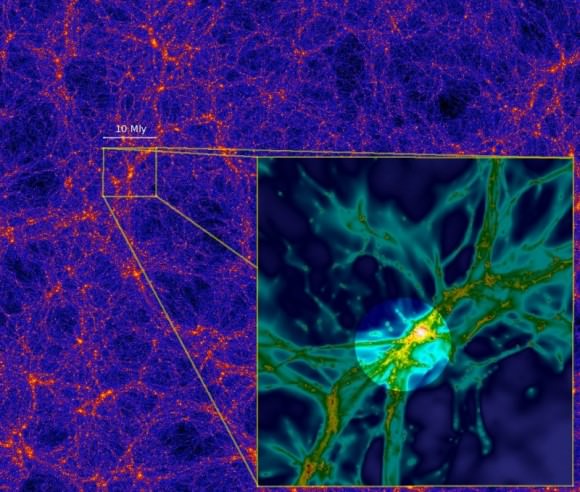

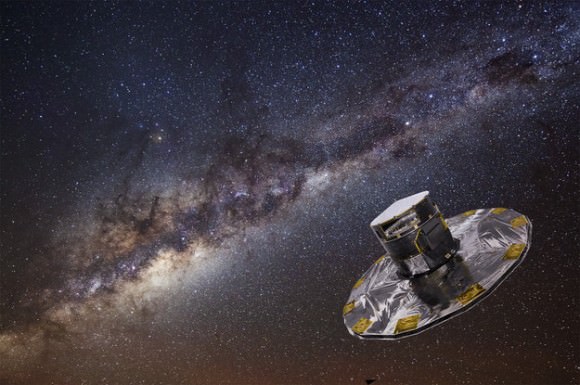

The team got a snapshot of these galaxies’ evolution by looking at a representative sample with the Hubble Space Telescope, specifically through the Cosmic Assembly Near-Infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey (CANDELS) and a spectroscopic survey called 3D-HST. To find out how old the stars were, they combined the Hubble work with data gathered from the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii.

Next, they examined ancient, fast-star-forming submillimeter galaxies with data gathered from a range of space and ground-based telescopes.

“This multi-spectral information, stretching from optical light through submillimeter wavelengths, yielded a full suite of information about the sizes, stellar masses, star-formation rates, dust content, and precise distances of the dust-enshrouded galaxies that were present early in the universe,” Hubble’s news center stated.

The group found that that the submillimeter galaxies were likely “progenitors” of compact elliptical galaxies, as they share predicted characteristics of the ancestors. Further, researchers calculated that starbursts in submillimeter galaxies only went on for about 40 million years before the galaxies ran out of gas.

You can read the results in the Feb. 20 edition of the Astrophysical Journal or in prepublished version in Arxiv.

Source: Hubble News Center