A stellar monster lurks in heart of the Centaur.

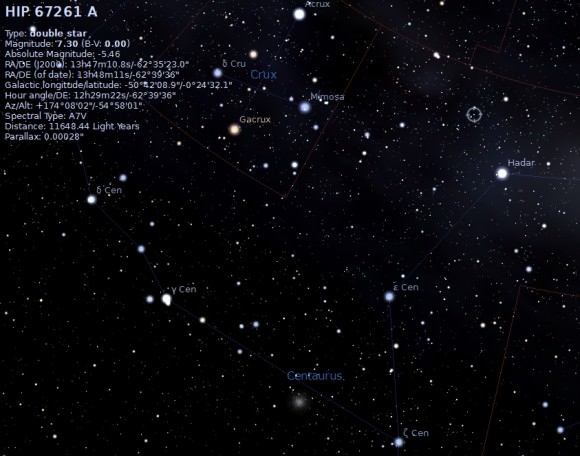

A recent analysis of a star in the south hemisphere constellation of Centaurus has highlighted the role that amateurs play in assisting with professional discoveries in astronomy.

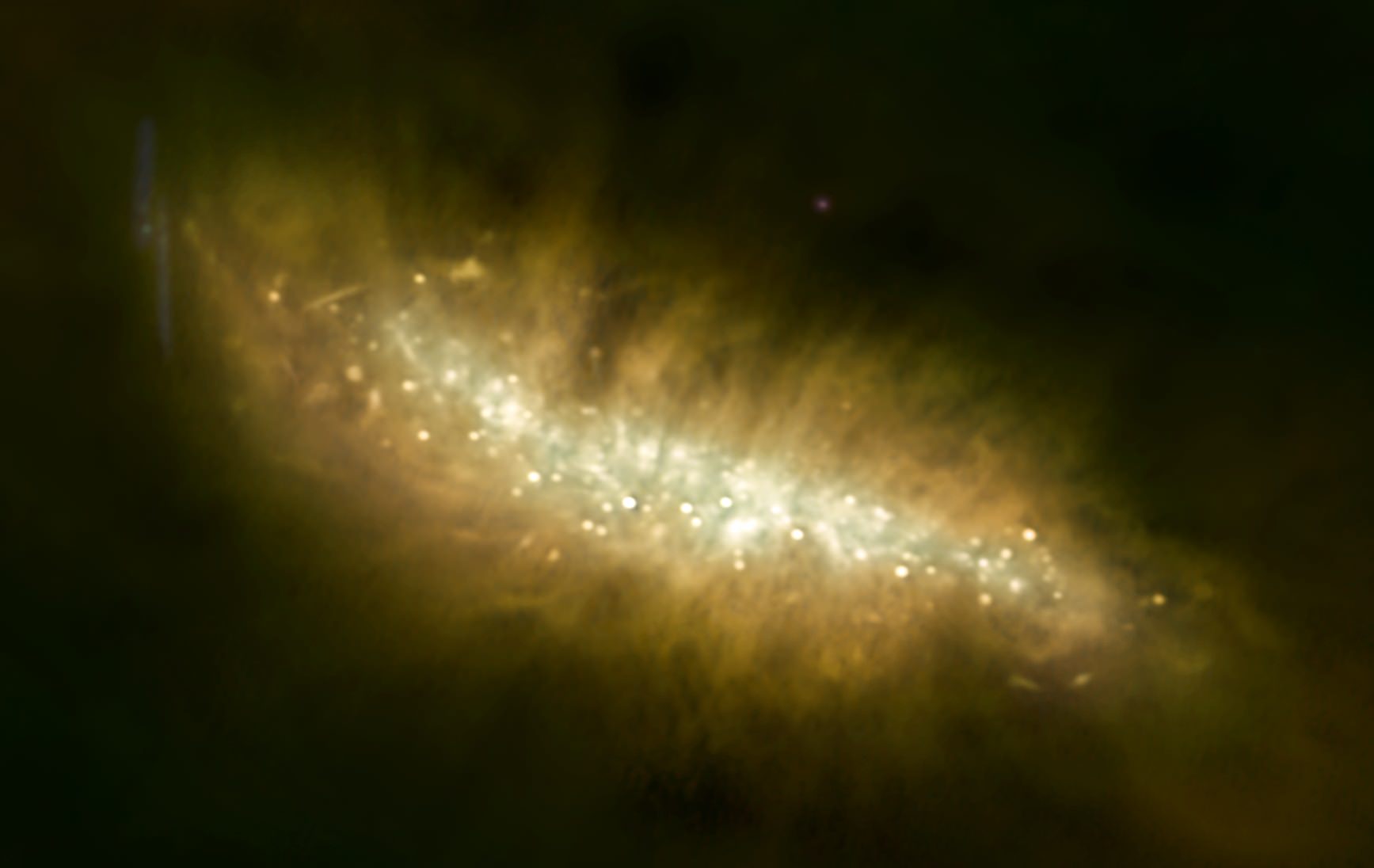

The find used of the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope based in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile — as well as data from observatories around the world — to reveal the nature of a massive yellow “hypergiant” star as one of the largest stars known.

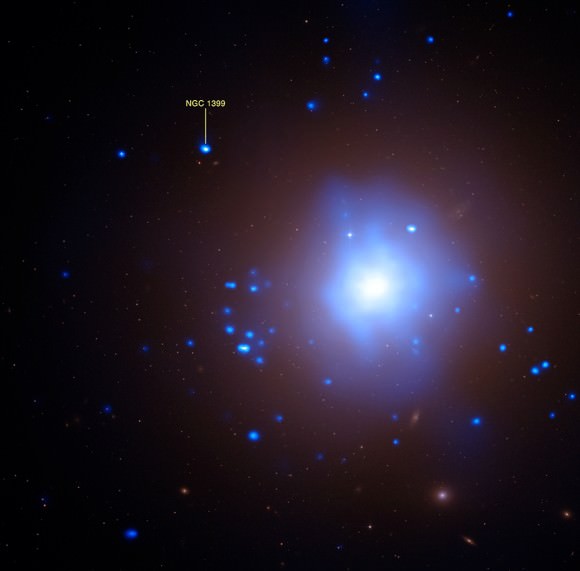

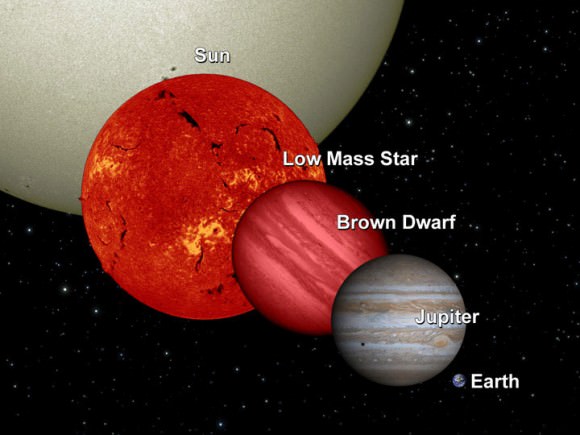

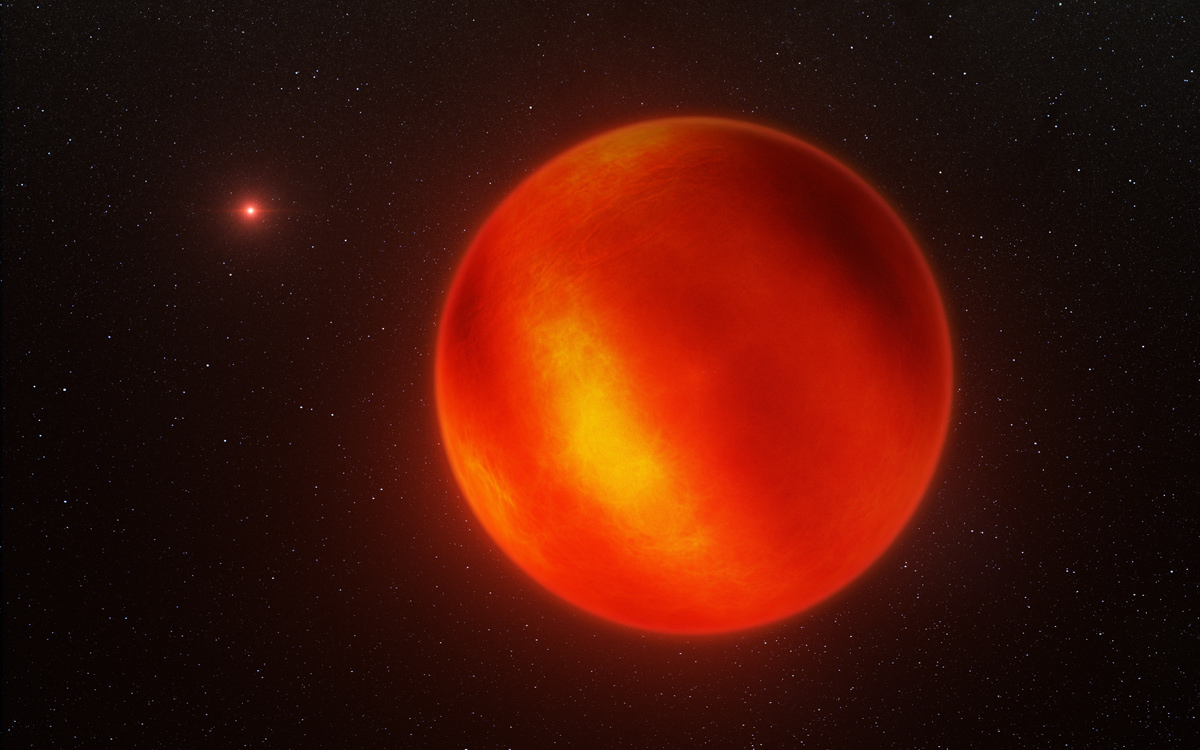

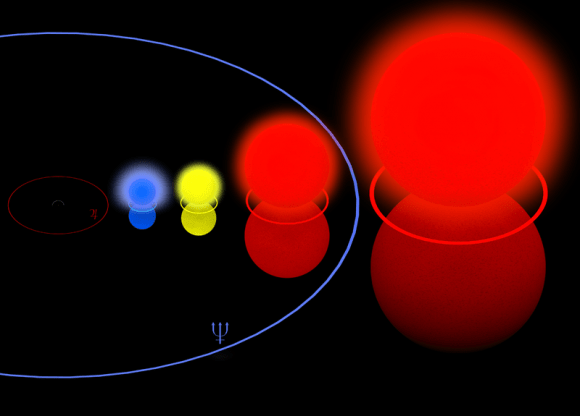

The stats for the star are impressive indeed: dubbed HR 5171 A, the binary system weighs in at a combined 39 solar masses, has a radius of over 1,300 times that of our Sun, and is a million times as luminous. Located 3,600 parsecs or over 11,700 light years distant, the star is 50% larger than the famous red giant Betelgeuse. Plop HR 5171 A down into the center of our own solar system, and it would extend out over 6 astronomical units (A.U.s) past the orbit of Jupiter.

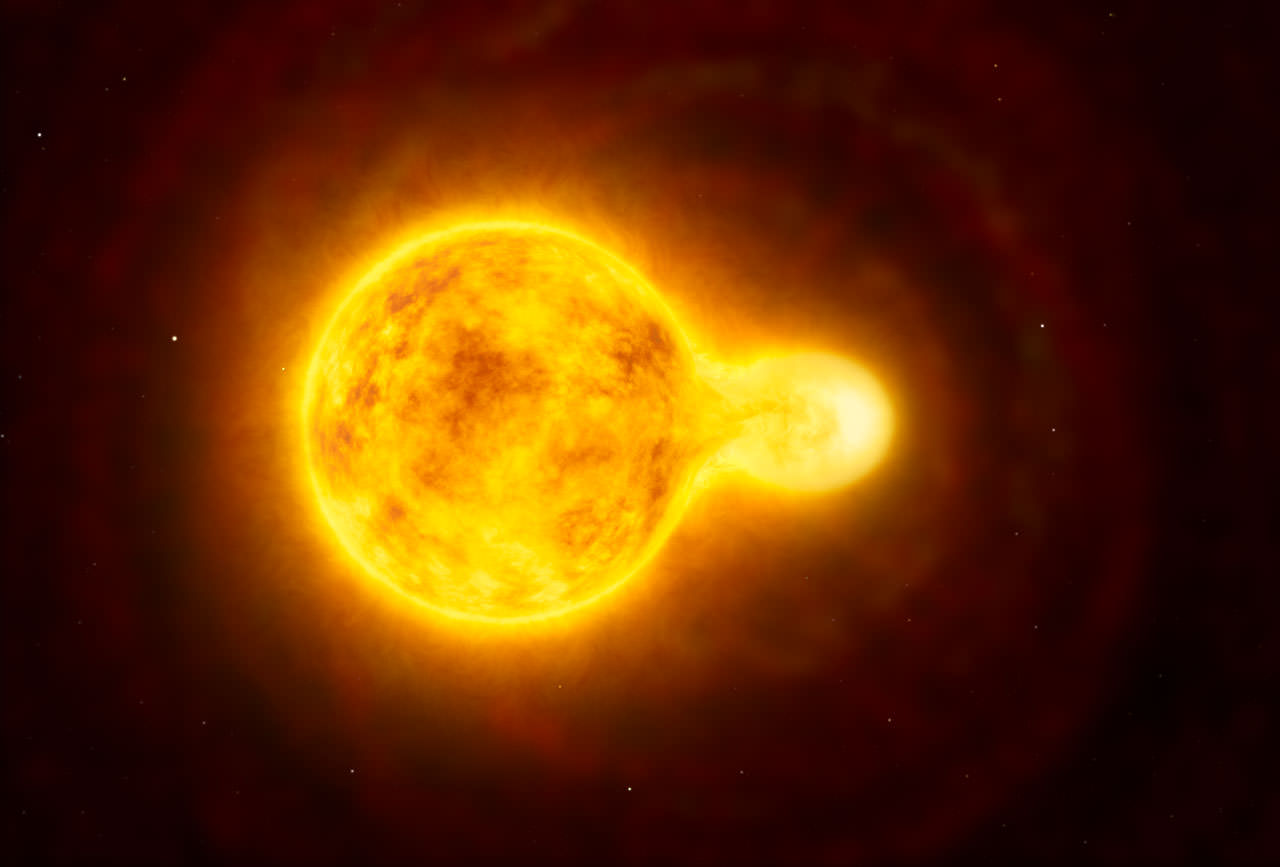

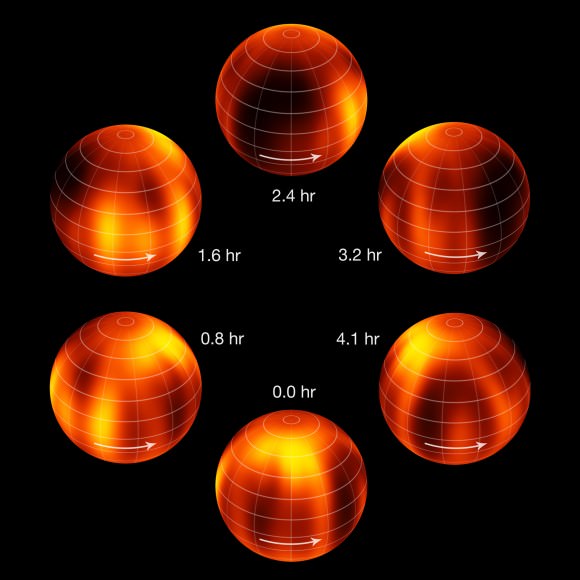

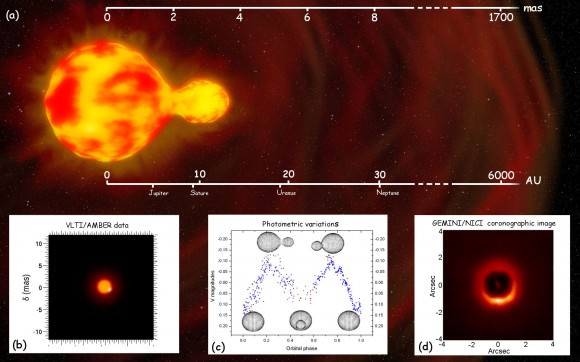

Researchers used observations going back over 60 years – some of which were collected by dedicated amateur astronomers – to pin down the nature of this curious star. A variable star just below naked eye visibility spanning a magnitude range from +6.1 to +7.3, HR 5171 A also has a relatively small companion star orbiting across our line of sight once every 1300 days. Such a system is known as an eclipsing binary. Famous examples of similar systems are the star Algol (Alpha Persei), Epsilon Aurigae and Beta Lyrae. The companion star for HR 5171 is also a large star in its own right at around six solar masses and 400 solar radii in size. The distance from center-to-center for the system is about 10 A.U.s – the distance from Sol to Saturn – and the surface-to-surface distance for the A and B components of the system are “only” about 2.8 A.U.s apart. This all means that these two massive stars are in physical contact, with the expanded outer atmosphere of the bloated primary contacting the secondary, giving the pair a distorted peanut shape.

“The companion we have found is very significant as it can have an influence on the fate of HR 5171 A, for example stripping off its outer layers and modifying its evolution,” said astronomer Olivier Chesneau of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in Nice France in the recent press release.

Knowing the orbital period of a secondary star offers a method to measure the mass of the primary using good old Newtonian mechanics. Coupled with astrometry used to measure its tiny parallax, this allows astronomers to pin down HR 5171 A’s stupendous size and distance.

Along with luminous blue variables, yellow hypergiants are some of the brightest stars known, with an absolute magnitude of around -9. That’s just 16x times fainter than the apparent visual magnitude of a Full Moon but over 100 times brighter than Venus – if you placed a star like HR 5171 A 32 light years from the Earth, it would easily cast a shadow.

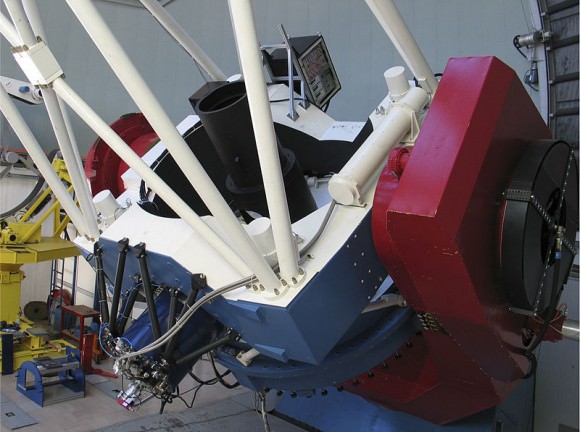

Astronomers used a technique known as interferormetry to study HR 5171 A, which involves linking up several telescopes to create the resolving power of one huge telescope. Researchers also culled through over a decade’s worth data to analyze the star. Though much of what had been collected by the American Association of Variable Star Observers (the AAVSO) had been considered to be too noisy for the purposes of this study, a dataset built from 2000 to 2013 by amateur astronomer Sebastian Otero was of excellent quality and provided a good verification for the VLT data.

The discovery is also crucial as researchers have come to realize that we’re catching HR 5171 A at an exceptional phase in its life. The star has been getting larger and cooling as it grows, and this change can be seen just over the past 40 year span of observations, a rarity in stellar astronomy.

“It’s not a surprise that yellow hypergiants are very instable and lose a lot of mass,” Chesneau told Universe Today. “But the discovery of a companion around such a bright star was a big surprise since any ‘normal’ star should at least be 10,000 times fainter than the hypergiant. Moreover, the hypergiant was much bigger than expected. What we see is not the companion itself, but the regions gravitationally controlled and filled by the wind from the hypergiant. This is a perfect example of the so-called Roche model. This is the first time that such a useful and important model has really been imaged. This hypergiant exemplifies a famous concept!”

Indeed, you can see just such photometric variations as the secondary orbits its host in the VLTI data collected by the AMBER interferometer, backed up by observations from GEMINI’s NICI chronograph:

The NIGHTFALL program was also used for modeling the eclipsing binary components.

These latest measurements place HR 5171 A firmly in the “Top 10” for largest stars in terms of size known, as well as the largest yellow hypergiant star known This is due mainly to tidal interactions with its companion. Only eight yellow hypergiants have been identified in our Milky Way galaxy. HR 5171 A is also in a crucial transition phase from a red hypergiant to becoming a luminous blue variable or perhaps even a Wolf-Rayet type star, and will eventually end its life as a supernova.

HR 5171 A is also known as HD 119796, HIP 67261, and V766 Centauri. Located at Right Ascension 13 Hours 47’ 11” and declination -62 degrees 35’ 23,” HR 5171 culminates just two degrees above the southern horizon at local midnight as seen from Miami in late March.

HR 5171 A is a fine binocular object for southern hemisphere observers.

But the good news is, there’s another yellow hypergiant visible for northern hemisphere observers named Rho Cassiopeiae:

Rho Cass is one of the few naked eye examples of a yellow hypergiant star, and varies from magnitude +4.1 to +6.2 over an irregular period.

It’s amusing read the Burnham’s Celestial Handbook entry on Rho Cass. He notes the lack of parallax and the spectral measurements of the day — the early 1960s — as eluding to a massive star with a “true distance… close to 3,000 light years!” Today we know that Rho Cassiopeiae actually lies farther still, at over 8,000 light years distant. Robert Burnham would’ve been impressed even more by the amazing nature of HR 5171 as revealed today by ESO astronomers!

– The AAVSO is always seeking observations from amateur astronomers of variable stars.