[/caption]

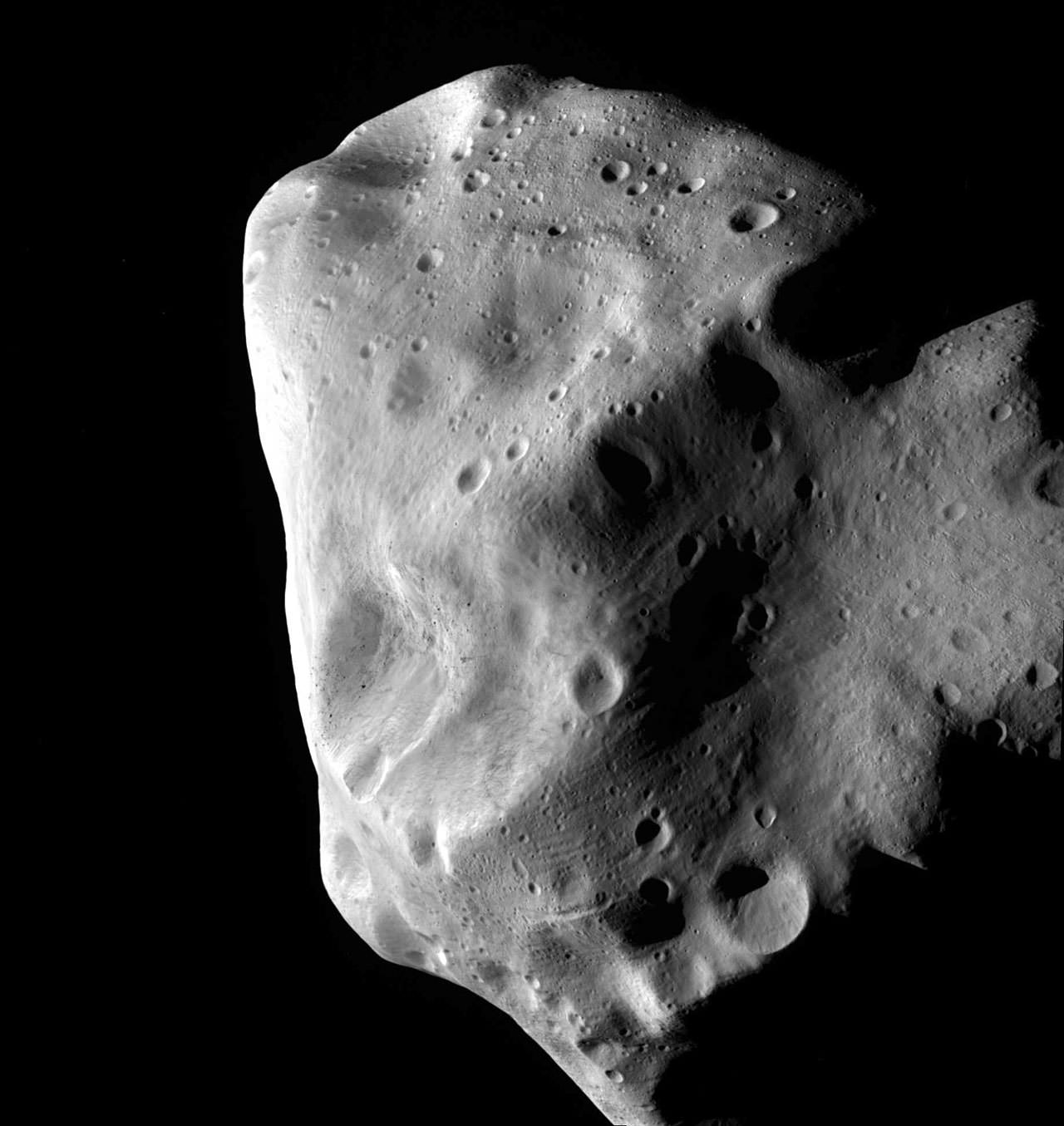

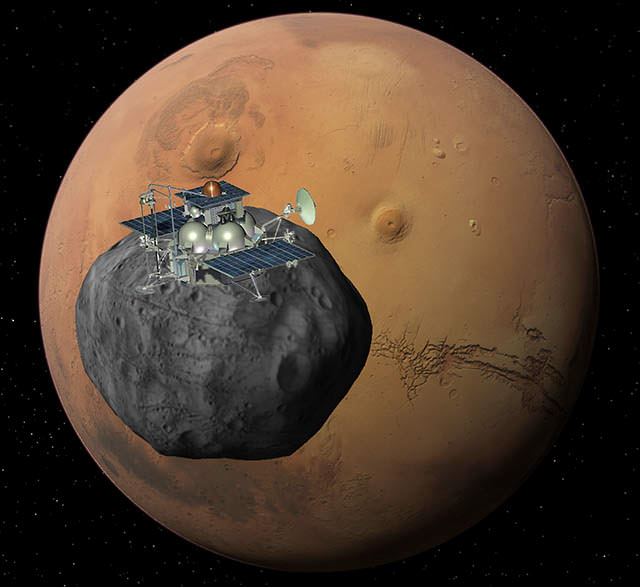

According to data received from ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft, ESO’s New Technology Telescope, and NASA telescopes, strange asteroid Lutetia could be a real piece of the rock… the original material that formed the Earth, Venus and Mercury! By examining precious meteors which may have formed at the time of the inner Solar System, scientists have found matching properties which indicate a relationship. Independent Lutetia must have just moved its way out to join in the main asteroid belt…

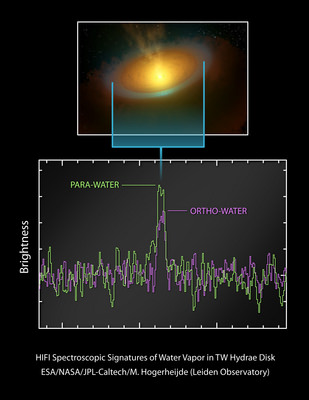

A team of astronomers from French and North American universities have been hard at work studying asteroid Lutetia spectroscopically. Data sets from the OSIRIS camera on ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft, ESO’s New Technology Telescope (NTT) at the La Silla Observatory in Chile, and NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii and Spitzer Space Telescope have been combined to give us a multi-wavelength look at this very different space rock. What they found was a very specific type of meteorite called an enstatite chondrite displayed similar content which matched Lutetia… and what is theorized as the material which dates back to the early Solar System. Chances are very good that enstatite chondrites are the same “stuff” which formed the rocky planets – Earth, Mars and Venus.

“But how did Lutetia escape from the inner Solar System and reach the main asteroid belt?” asks Pierre Vernazza (ESO), the lead author of the paper.

It’s a very good question considering that an estimated less than 2% of the material which formed in the same region of Earth migrated to the main asteroid belt. Within a few million years of formation, this type of “debris” had either been incorporated into the gelling planets or else larger pieces had escaped to a safer, more distant orbit from the Sun. At about 100 kilometers across, Lutetia may have been gravitationally influenced by a close pass to the rocky planets and then further affected by a young Jupiter.

“We think that such an ejection must have happened to Lutetia. It ended up as an interloper in the main asteroid belt and it has been preserved there for four billion years,” continues Pierre Vernazza.

Asteroid Lutetia is a “real looker” and has long been a source of speculation due to its unusual color and surface properties. Only 1% of the asteroids located in the main belt share its rare characteristics.

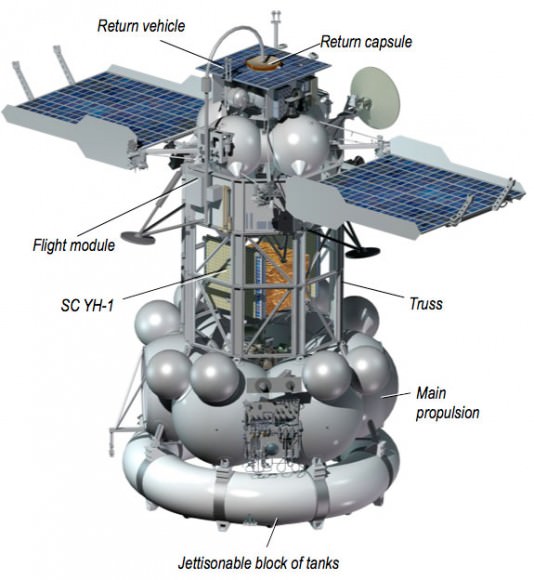

“Lutetia seems to be the largest, and one of the very few, remnants of such material in the main asteroid belt. For this reason, asteroids like Lutetia represent ideal targets for future sample return missions. We could then study in detail the origin of the rocky planets, including our Earth,” concludes Pierre Vernazza.

Original Story Source: ESO News Release.