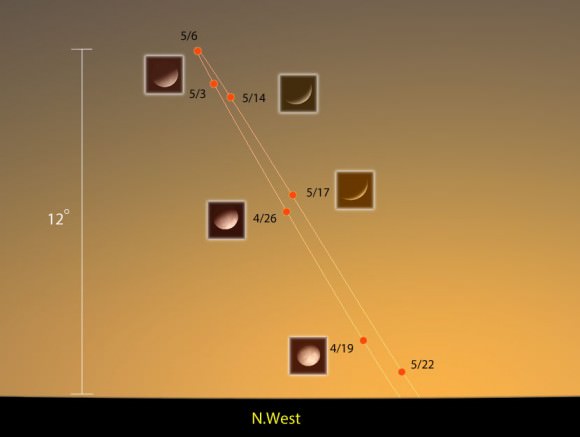

Have you ever seen Mercury? The diminutive innermost world takes the center stage next month, as it transits the Sun as seen from our early perspective on May 9th. This week, we’d like to turn your attention to bashful Mercury’s dusk apparition, which sets up the clockwork celestial gears for this event. Continue reading “Prelude to Transit: Catching Mercury Under Dusk Skies”

Dark Stains on Mercury Reveal Its Ancient Crust

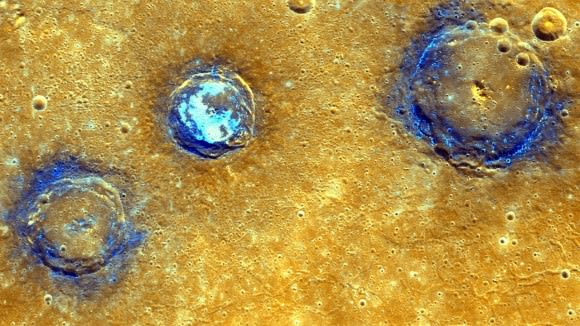

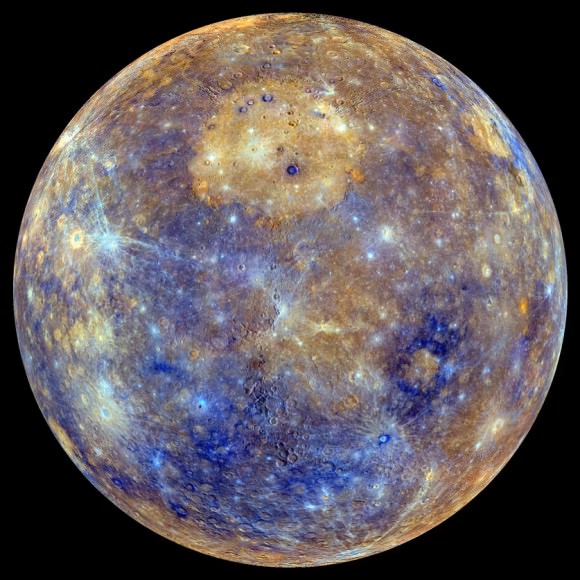

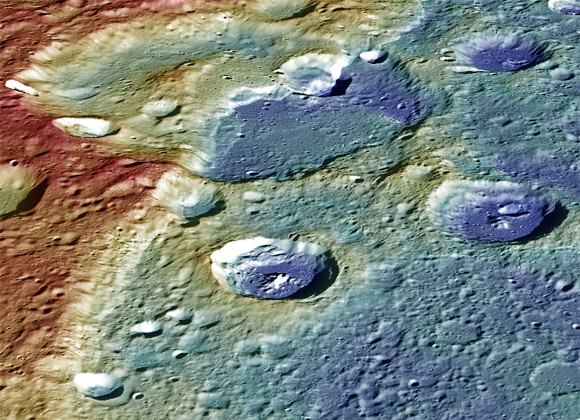

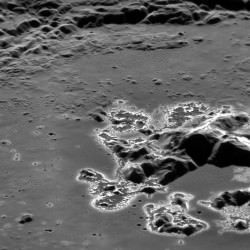

Ever since the MESSENGER spacecraft entered orbit around Mercury in 2011, and indeed even since Mariner 10‘s flyby in 1974, peculiar “dark spots” observed on the planet’s surface have intrigued scientists as to their composition and origin. Now, thanks to high-resolution spectral data acquired by MESSENGER during the last few months of its mission, researchers have confirmed that Mercury’s dark spots contain a form of carbon called graphite, excavated from the planet’s original, ancient crust.

Continue reading “Dark Stains on Mercury Reveal Its Ancient Crust”

How Many Moons Does Mercury Have?

Virtually every planet in the Solar System has moons. Earth has The Moon, Mars has Phobos and Deimos, and Jupiter and Saturn have 67 and 62 officially named moons, respectively. Heck, even the recently-demoted dwarf planet Pluto has five confirmed moons – Charon, Nix, Hydra, Kerberos and Styx. And even asteroids like 243 Ida may have satellites orbiting them (in this case, Dactyl). But what about Mercury?

If moons are such a common feature in the Solar System, why is it that Mercury has none? Yes, if one were to ask how many satellites the planet closest to our Sun has, that would be the short answer. But answering it more thoroughly requires that we examine the process through which other planets acquired their moons, and seeing how these apply (or fail to apply) to Mercury.

MESSENGER Spies a Meteor Shower… on Mercury

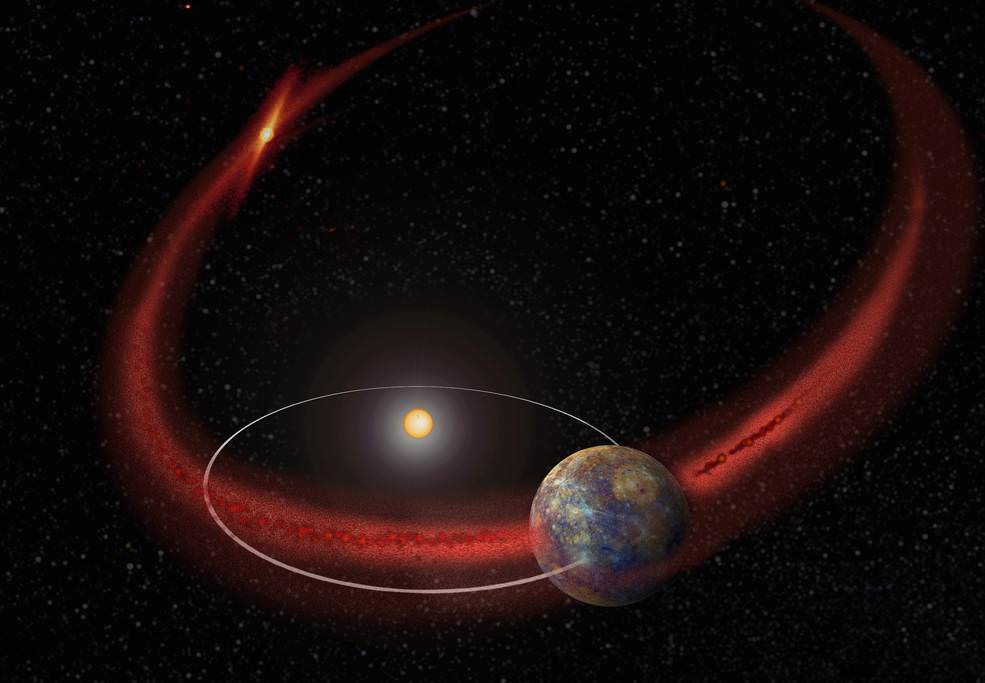

Leonid meteor storms. Taurid meteor swarms. Earth is no stranger to meteor showers, that’s for sure. Now, it turns out that the planet Mercury may experience periodic meteor showers as well.

The news of extraterrestrial meteor showers on Mercury came out of the annual Meeting of the Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society currently underway this week in National Harbor, Maryland. The study was carried out by Rosemary Killen of NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center, working with Matthew Burger of Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland and Apostolos Christou from the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland. The study looked at data from the MErcury Surface Space Environment Geochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft, which orbited Mercury until late April of this year. Astronomers published the results in the September 28th issue of Geophysical Research Letters.

Micrometeoroid debris litters the ecliptic plane, the result of millions of years of passages of comets through the inner solar system. You can see evidence of this in the band of the zodiacal light visible at dawn or dusk from a dark sky site, and the elusive counter-glow of the gegenschein.

Researchers have tagged meteoroid impacts as a previous source of the tenuous exosphere tails exhibited by otherwise airless worlds such as Mercury. The impacts kick up a detectable wind of calcium particles as Mercury plows through the zodiacal cloud of debris.

“We already knew that impacts were important in producing exospheres,” says Killen in a recent NASA Goddard press release. “What we did not know was the relative importance of comet streams over zodiacal dust.”

This calcium peak, however, posed a mystery to researchers. Namely, the peak was occurring just after perihelion—Mercury orbits the Sun once every 88 Earth days, and travels from 0.31 AU from the Sun at perihelion to 0.47 AU at aphelion—versus an expected calcium peak predicted by researchers just before perihelion.

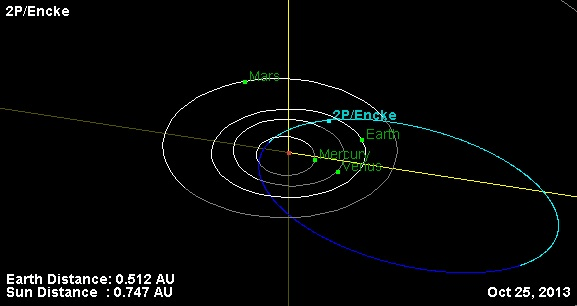

A key suspect in the calcium meteor spike dilemma came in the way of periodic Comet 2P Encke. Orbiting the Sun every 3.3 years—the shortest orbit of any known periodic comet—2P Encke has made many passages through the inner solar system, more than enough to lay down a dense and stable meteoroid debris stream over the millennia.

With an orbit ranging from a perihelion at 0.3 AU interior to Mercury’s to 4 AU, debris from Encke visits Earth as well in the form of the November Taurid Fireballs currently gracing the night skies of the Earth.

The Encke connection still presented a problem: the cometary stream is closest to the orbit of Mercury about a week later than the observed calcium peak. It was as if the stream had drifted over time…

Enter the Poynting-Robertson effect. This is a drag created by solar radiation pressure over time. The push on cometary dust grains thanks to the Poynting-Robertson effect is tiny, but it does add up over time, modifying and moving meteor streams. We see this happening in our own local meteor stream environment, as once great showers such as the late 19th century Andromedids fade into obscurity. The gravitational influence of the planets also plays a role in the evolution of meteor shower streams as well.

Researchers in the study re-ran the model, using MESSENGER data and accounting for the Poynting-Robertson effect. They found the peak of the calcium emissions seen today are consistent with millimeter-sized grains ejected from Comet Encke about 10,000 to 20,000 years ago. That grain size and distribution is important, as bigger, more massive grains result in a smaller drag force.

This finding shows the role and mechanism that cometary debris plays in exosphere production on worlds like Mercury.

“Finding that we can move the location of stream to match MESSENGER’s observations is gratifying, but the fact that the shift agrees with what we know about Encke and its stream from independent source makes us confident that the cause-and-effect relationship is real, says Christou in this week’s NASA Goddard press release.

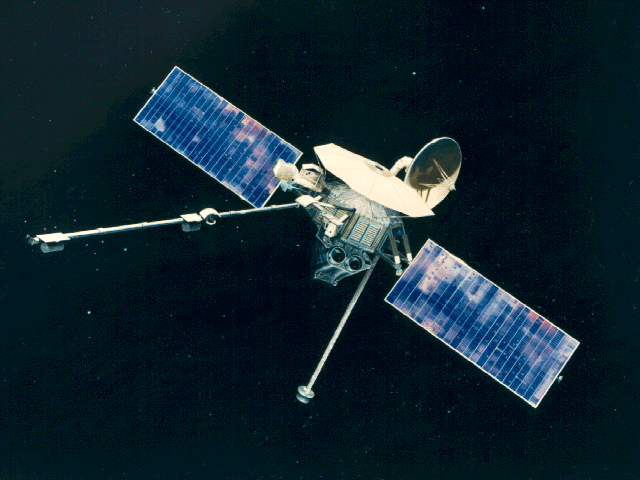

Launched in 2004, MESSENGER arrived at Mercury in March 2011 and orbited the world for over four years, the first spacecraft to do so. MESSENGER mapped the entire surface of Mercury for the first time, and became the first human-made artifact to impact Mercury on April 30th, 2015.

The joint JAXA/ESA mission BepiColombo is the next Mercury mission in the pipeline, set to leave Earth on 2017 for insertion into orbit around Mercury on 2024.

An interesting find on the innermost world, and a fascinating connection between Earth and Mercury via comet 2P Encke and the Taurid Fireballs.

Tricks to Remember the Planets

Need an easy way to remember the order of the planets in our Solar System? The technique used most often to remember such a list is a mnemonic device. This uses the first letter of each planet as the first letter of each word in a sentence. Supposedly, experts say, the sillier the sentence, the easier it is to remember.

So by using the first letters of the planets, (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune), create a silly but memorable sentence.

Here are a few examples:

- My Very Excellent Mother Just Served Us Noodles (or Nachos)

- Mercury’s Volcanoes Erupt Mulberry Jam Sandwiches Until Noon

- Very Elderly Men Just Snooze Under Newspapers

- My Very Efficient Memory Just Summed Up Nine

- My Very Easy Method Just Speeds Up Names

- My Very Expensive Malamute Jumped Ship Up North

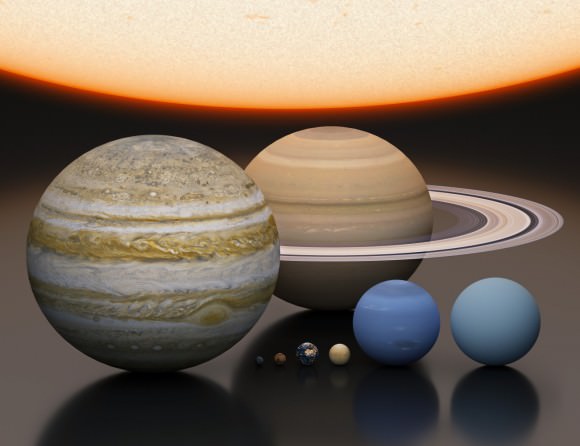

The Sun and planets to scale. Credit: Illustration by Judy Schmidt, texture maps by Björn Jónsson If you want to remember the planets in order of size, (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Earth, Venus Mars, Mercury) you can create a different sentence:

- Just Sit Up Now Each Monday Morning

- Jack Sailed Under Neath Every Metal Mooring

Rhymes are also a popular technique, albeit they require memorizing more words. But if you’re a poet (and don’t know it) try this:

Amazing Mercury is closest to the Sun,

Hot, hot Venus is the second one,

Earth comes third: it’s not too hot,

Freezing Mars awaits an astronaut,

Jupiter is bigger than all the rest,

Sixth comes Saturn, its rings look best,

Uranus sideways falls and along with Neptune, they are big gas balls.Or songs can work too. Here are a couple of videos that use songs to remember the planets:

If sentences, rhymes or songs don’t work for you, perhaps you are more of a visual learner, as some people remember visual cues better than words. Try drawing a picture of the planets in order. You don’t have to be an accomplished artist to do this; you can simply draw different circles for each planet and label each one. Sometimes color-coding can help aid your memory. For example, use red for Mars and blue for Neptune. Whatever you decide, try to pick colors that are radically different to avoid confusing them.

Or try using Solar System flash cards or just pictures of the planets printed on a page (here are some great pictures of the planets). This works well because not only are you recalling the names of the planets but also what they look like. Memory experts say the more senses you involve in learning or storing something, the better you will be at recalling it.

Planets made from paper lanterns. Credit: TheSweetestOccasion.com Maybe you are a hands-on learner. If so, try building a three-dimensional model of the Solar System. Kids, ask your parents or guardians to help you with this, or parents/guardians, this is a fun project to do with your children. You can buy inexpensive Styrofoam balls at your local craft store to create your model, or use paper lanterns and decorate them. Here are several ideas from Pinterest on building a 3-D Solar System Model.

If you are looking for a group project to help a class of children learn the planets, have a contest to see who comes up with the silliest sentence to remember the planets. Additionally, you can have eight children act as the planets while the rest of the class tries to line them up in order. You can find more ideas on NASA’s resources for Educators. You can use these tricks as a starting point and find more ways of remembering the planets that work for you.

If you are looking for more information on the planets check out Universe Today’s Guide to the Planets section, or our article about the Order of the Planets, or this information from NASA on the planets and a tour of the planets.

Universe Today has numerous articles on the planets including the planets and list of the planets.

Astronomy Cast has an entire series of episodes on the planets. You can get started with Mercury.

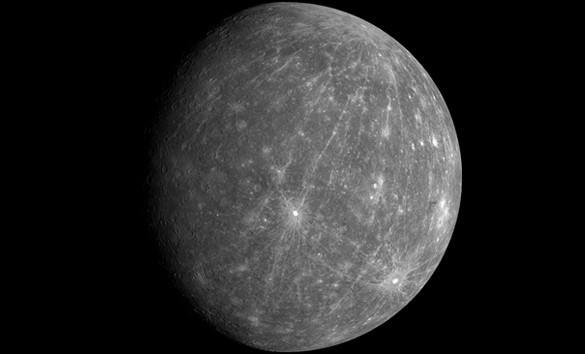

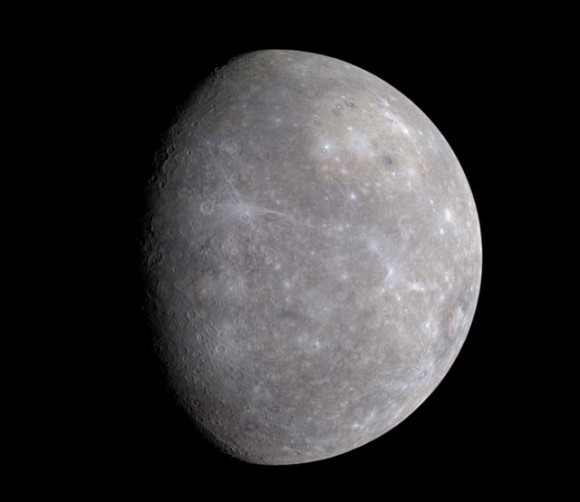

The Planet Mercury

Mercury is the closest planet to our Sun, the smallest of the eight planets, and one of the most extreme worlds in our Solar Systems. Named after the Roman messenger of the gods, the planet is one of a handful that can be viewed without the aid of a telescope. As such, it has played an active role in the mythological and astrological systems of many cultures.

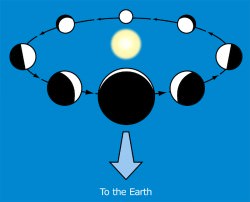

In spite of that, Mercury is one of the least understood planets in our Solar System. Much like Venus, its orbit between Earth and the Sun means that it can be seen at both morning and evening (but never in the middle of the night). And like Venus and the Moon, it also goes through phases; a characteristic which originally confounded astronomers, but eventually helped them to realize the true nature of the Solar System.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

With a mean radius of 2440 km and a mass of 3.3022×1023 kg, Mercury is the smallest planet in our Solar System – equivalent in size to 0.38 Earths. And while it is smaller than the largest natural satellites in our system – such as Ganymede and Titan – it is more massive. In fact, Mercury’s density (at 5.427 g/cm3) is the second-highest in the Solar System, only slightly less than Earth’s (5.515 g/cm3).

Mercury has the most eccentric orbit of any planet in the Solar System (0.205). Because of this, its distance from the Sun varies between 46 million km (29 million mi) at its closest (perihelion) to 70 million km (43 million mi) at its farthest (aphelion). And with an average orbital velocity of 47.362 km/s (29.429 mi/s), it takes Mercury a total of 87.969 Earth days to complete a single orbit.

With an average rotational speed of 10.892 km/h (6.768 mph), Mercury also takes 58.646 days to complete a single rotation. This means that Mercury has a spin-orbit resonance of 3:2, which means that it completes three rotations on its axis for every two rotations around the Sun. This does not, however, mean that three days last the same as two years on Mercury.

In fact, its high eccentricity and slow rotation mean that it takes 176 Earth days for the Sun to return to the same place in the sky (aka. a solar day). This means that a single day on Mercury is twice as long as a single year. Mercury also has the lowest axial tilt of any planet in the Solar System – approximately 0.027 degrees compared to Jupiter’s 3.1 degrees (the second smallest).

Composition and Surface Features:

As one of the four terrestrial planets of the Solar System, Mercury is composed of approximately 70% metallic and 30% silicate material. Based on its density and size, a number of inferences can be made about its internal structure. For example, geologists estimate that Mercury’s core occupies about 42% of its volume, compared to Earth’s 17%.

The interior is believed to be composed of molten iron which is surrounded by a 500 – 700 km mantle of silicate material. At the outermost layer is Mercury’s crust, which is believed to be 100 – 300 km thick. The surface is also marked by numerous narrow ridges that extend up to hundreds of kilometers in length. It is believed that these were formed as Mercury’s core and mantle cooled and contracted at a time when the crust had already solidified.

Mercury’s core has a higher iron content than that of any other major planet in the Solar System, and several theories have been proposed to explain this. The most widely accepted theory is that Mercury was once a larger planet which was struck by a planetesimal measuring several thousand km in diameter. This impact could have then stripped away much of the original crust and mantle, leaving behind the core as a major component.

Another theory is that Mercury may have formed from the solar nebula before the Sun’s energy output had stabilized. In this scenario, Mercury would have originally been twice its present mass but would have been subjected to temperatures of 25,000 to 35,000 K (or as high as 10,000 K) as the protosun contracted. This process would have vaporized much of Mercury’s surface rock, reducing it to its current size and composition.

A third hypothesis is that the solar nebula created drag on the particles from which Mercury was accreting, which meant that lighter particles were lost and not gathered to form Mercury. Naturally, further analysis is needed before any of these theories can be confirmed or ruled out.

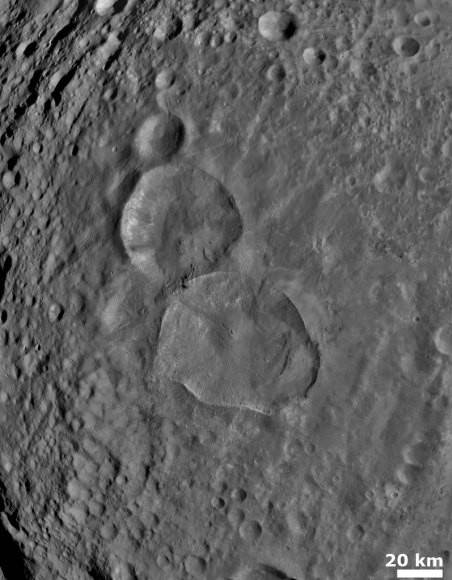

At a glance, Mercury looks similar to the Earth’s moon. It has a dry landscape pockmarked by asteroid impact craters and ancient lava flows. Combined with extensive plains, these indicate that the planet has been geologically inactive for billions of years. However, unlike the Moon and Mars, which have significant stretches of similar geology, Mercury’s surface appears much more jumbled. Other common features include dorsa (aka. “wrinkle-ridges”), Moon-like highlands, montes (mountains), planitiae (plains), rupes (escarpments), and valles (valleys).

Names for these features come from a variety of sources. Craters are named for artists, musicians, painters, and authors; ridges are named for scientists; depressions are named after works of architecture; mountains are named for the word “hot” in different languages; planes are named for Mercury in various languages; escarpments are named for ships of scientific expeditions, and valleys are named after radio telescope facilities.

During and following its formation 4.6 billion years ago, Mercury was heavily bombarded by comets and asteroids, and perhaps again during the Late Heavy Bombardment period. During this period of intense crater formation, the planet received impacts over its entire surface, thanks in part to the lack of any atmosphere to slow impactors down. During this time, the planet was volcanically active, and released magma would have produced the smooth plains.

Craters on Mercury range in diameter from small bowl-shaped cavities to multi-ringed impact basins hundreds of kilometers across. The largest known crater is Caloris Basin, which measures 1,550 km in diameter. The impact that created it was so powerful that it caused lava eruptions on the other side of the planet and left a concentric ring over 2 km tall surrounding the impact crater. Overall, about 15 impact basins have been identified on those parts of Mercury that have been surveyed.

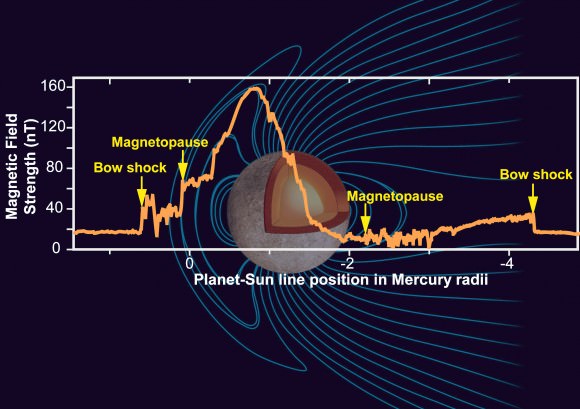

Despite its small size and slow 59-day-long rotation, Mercury has a significant, and apparently global, magnetic field that is about 1.1% the strength of Earth’s. It is likely that this magnetic field is generated by a dynamo effect, in a manner similar to the magnetic field of Earth. This dynamo effect would result from the circulation of the planet’s iron-rich liquid core.

Mercury’s magnetic field is strong enough to deflect the solar wind around the planet, thus creating a magnetosphere. The planet’s magnetosphere, though small enough to fit within Earth, is strong enough to trap solar wind plasma, which contributes to the space weathering of the planet’s surface.

Atmosphere and Temperature:

Mercury is too hot and too small to retain an atmosphere. However, it does have a tenuous and variable exosphere that is made up of hydrogen, helium, oxygen, sodium, calcium, potassium, and water vapor, with a combined pressure level of about 10-14 bar (one-quadrillionth of Earth’s atmospheric pressure). It is believed this exosphere was formed from particles captured from the Sun, volcanic outgassing and debris kicked into orbit by micrometeorite impacts.

Because it lacks a viable atmosphere, Mercury has no way to retain the heat from the Sun. As a result of this and its high eccentricity, the planet experiences considerable variations in temperature. Whereas the side that faces the Sun can reach temperatures of up to 700 K (427° C), while the side in shadow dips down to 100 K (-173° C).

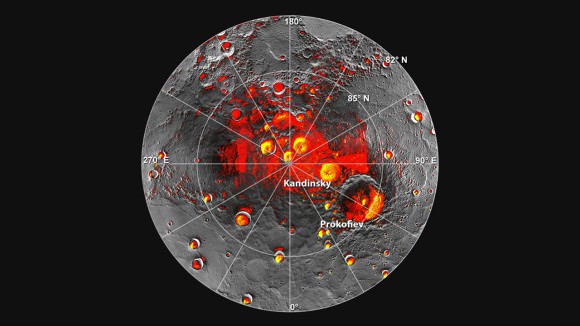

Despite these highs in temperature, the existence of water ice and even organic molecules has been confirmed on Mercury’s surface. The floors of deep craters at the poles are never exposed to direct sunlight, and temperatures there remain below the planetary average.

These icy regions are believed to contain about 1014–1015 kg of frozen water and may be covered by a layer of regolith that inhibits sublimation. The origin of the ice on Mercury is not yet known, but the two most likely sources are from outgassing of water from the planet’s interior or deposition by the impacts of comets.

Historical Observations:

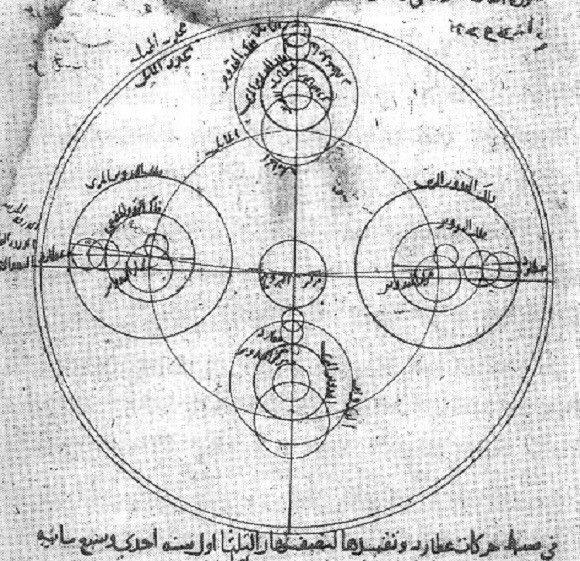

Much like the other planets that are visible to the naked eye, Mercury has a long history of being observed by human astronomers. The earliest recorded observations of Mercury are believed to be from the Mul Apin tablet, a compendium of Babylonian astronomy and astrology.

The observations, which were most likely made during the 14th century BCE, refer to the planet as “the jumping planet”. Other Babylonian records, which refer to the planet as “Nabu” (after the messenger to the gods in Babylonian mythology) date back to the first millennium BCE. The reason for this has to do with Mercury being the fastest-moving planet across the sky.

To the ancient Greeks, Mercury was known variously as “Stilbon” (a name which means “the gleaming”), Hermaon, and Hermes. As with the Babylonians, this latter name came from the messenger of the Greek pantheon. The Romans continued this tradition, naming the planet Mercurius after the swift-footed messenger of the gods, which they equated with the Greek Hermes.

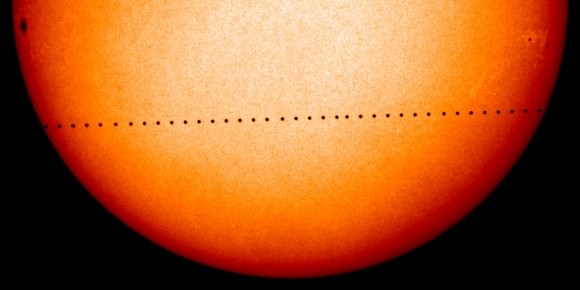

In his book Planetary Hypotheses, Greco-Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy wrote about the possibility of planetary transits across the face of the Sun. For both Mercury and Venus, he suggested that no transits had been observed because the planet was either too small to see or because the transits are too infrequent.

To the ancient Chinese, Mercury was known as Chen Xing (“the Hour Star”) and was associated with the direction of north and the element of water. Similarly, modern Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese cultures refer to the planet literally as the “water star” based on the Five Elements. In Hindu mythology, the name Budha was used for Mercury – the god that was thought to preside over Wednesday.

The same is true of the Germanic tribes, who associated the god Odin (or Woden) with the planet Mercury and Wednesday. The Maya may have represented Mercury as an owl – or possibly four owls, two for the morning aspect and two for the evening – that served as a messenger to the underworld.

In medieval Islamic astronomy, the Andalusian astronomer Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Zarqali in the 11th century described Mercury’s geocentric orbit as being oval, although this insight did not influence his astronomical theory or his astronomical calculations. In the 12th century, Ibn Bajjah observed: “two planets as black spots on the face of the Sun”, which was later suggested as the transit of Mercury and/or Venus.

In India, the Kerala school astronomer Nilakantha Somayaji in the 15th century developed a partially heliocentric planetary model in which Mercury orbits the Sun, which in turn orbits Earth, similar to the system proposed by Tycho Brahe in the 16th century.

The first observations using a telescope took place in the early 17th century by Galileo Galilei. Although he had observed phases when looking at Venus, his telescope was not powerful enough to see Mercury going through similar phases. In 1631, Pierre Gassendi made the first telescopic observations of the transit of a planet across the Sun when he saw a transit of Mercury, which had been predicted by Johannes Kepler.

In 1639, Giovanni Zupi used a telescope to discover that the planet had orbital phases similar to Venus and the Moon. These observations demonstrated conclusively that Mercury orbited around the Sun, which helped to definitively prove that the Copernican Heliocentric model of the universe was the correct one.

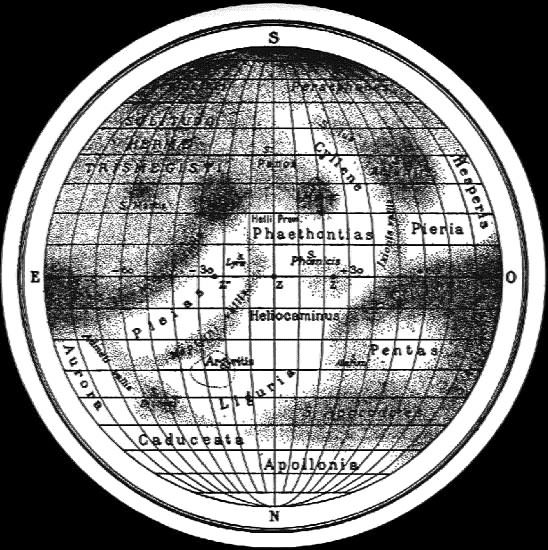

In the 1880s, Giovanni Schiaparelli mapped the planet more accurately and suggested that Mercury’s rotational period was 88 days, the same as its orbital period due to tidal locking. The effort to map the surface of Mercury was continued by Eugenios Antoniadi, who published a book in 1934 that included both maps and his own observations. Many of the planet’s surface features, particularly the albedo features, take their names from Antoniadi’s map.

In June of 1962, Soviet scientists at the USSR Academy of Sciences became the first to bounce a radar signal off Mercury and receive it, which began the era of using radar to map the planet. Three years later, Americans Gordon Pettengill and R. Dyce conducted radar observations using the Arecibo Observatory’s radio telescope. Their observations demonstrated conclusively that the planet’s rotational period was about 59 days and the planet did not have a synchronous rotation (which was widely believed at the time).

Ground-based optical observations did not shed much further light on Mercury, but radio astronomers using interferometry at microwave wavelengths – a technique that enables removal of the solar radiation – were able to discern physical and chemical characteristics of the subsurface layers to a depth of several meters.

In 2000, high-resolution observations were conducted by the Mount Wilson Observatory which provided the first views that resolved surface features on previously unseen parts of the planet. Most of the planet has been mapped by the Arecibo radar telescope, with 5 km resolution, including polar deposits in shadowed craters of what was believed to be water ice.

Exploration:

Prior to the first space probes flying past Mercury, many of its most fundamental morphological properties remained unknown. The first of these was NASA’s Mariner 10, which flew past the planet between 1974 and 1975. During the course of its three close approaches to the planet, it was able to capture the first close-up images of Mercury’s surface, which revealed heavily cratered terrain, giant scarps, and other surface features.

Unfortunately, due to the length of Mariner 10‘s orbital period, the same face of the planet was lit at each of Mariner 10‘s close approaches. This made observation of both sides of the planet impossible and resulted in the mapping of less than 45% of the planet’s surface.

During its first close approach, instruments also detected a magnetic field, to the great surprise of planetary geologists. The second close approach was primarily used for imaging, but at the third approach, extensive magnetic data were obtained. The data revealed that the planet’s magnetic field is much like Earth’s, which deflects the solar wind around the planet.

On March 24th, 1975, just eight days after its final close approach, Mariner 10 ran out of fuel, prompting its controllers to shut the probe down. Mariner 10 is thought to be still orbiting the Sun, passing close to Mercury every few months.

The second NASA mission to Mercury was the MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (or MESSENGER) space probe. The purpose of this mission was to clear up six key issues relating to Mercury, namely – its high density, its geological history, the nature of its magnetic field, the structure of its core, whether it has ice at its poles, and where its tenuous atmosphere comes from.

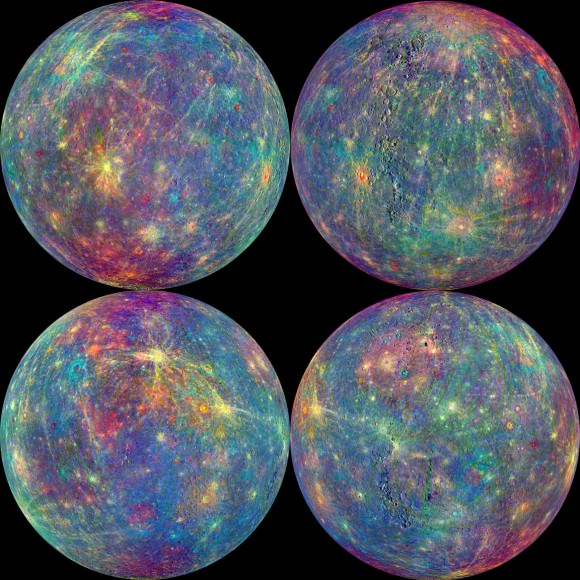

To this end, the probe carried imaging devices that gathered much higher-resolution images of much more of the planet than Mariner 10, assorted spectrometers to determine abundances of elements in the crust, and magnetometers and devices to measure velocities of charged particles.

Having launched from Cape Canaveral on August 3rd, 2004, it made its first flyby of Mercury on January 14th, 2008, a second on October 6th, 2008, and a third on September 29th, 2009. Most of the hemisphere not imaged by Mariner 10 was mapped during these fly-bys. On March 18th, 2011, the probe successfully entered an elliptical orbit around the planet and began taking images by March 29th.

After finishing its one-year mapping mission, it then entered a one-year extended mission that lasted until 2013. MESSENGER’s final maneuver took place on April 24th, 2015, which left it without fuel and an uncontrolled trajectory that inevitably led it to crash into Mercury’s surface on April 30th, 2015.

In 2016, the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace and Exploration Agency (JAXA) plan to launch a joint mission called BepiColombo. This robotic space probe, which is expected to reach Mercury by 2024, will orbit Mercury with two probes: a mapper probe and a magnetosphere probe.

The magnetosphere probe will be released into an elliptical orbit, then fire its chemical rockets to deposit the mapper probe into a circular orbit. The mapper probe will then go on to study the planet in many different wavelengths – infrared, ultraviolet, X-ray, and gamma-ray – using an array of spectrometers similar to those on MESSENGER.

Yes, Mercury is a planet of extremes and is riddled with contradictions. It ranges from extreme hot to extreme cold; it has a molten surface but also has water ice and organic molecules on its surface, and it has no discernible atmosphere but possessing an exosphere and magnetosphere. Combined with its proximity to the Sun, it is little wonder why we don’t know much about this terrestrial world.

One can only hope that the technology exists in the future for us to get closer to this world and study its extremes more thoroughly.

In the meantime, here are some articles on Mercury that we hope you find interesting, illuminating, and fun to read:

Location and Movement of Mercury:

- Rotation of Mercury

- Orbit of Mercury

- How Long is a Day on Mercury

- How Long is a Year on Mercury?

- Mercury Retrograde

- Mercury Revolution

- Length of Day on Mercury

- Length of Year on Mercury

- Transit of Mercury

- How Long Does it Take Mercury to Orbit the Sun?

Structure of Mercury:

- Mercury Diagram

- Interior of Mercury

- Composition of Mercury

- Formation of Mercury

- What is Mercury Made Of?

- What Type of Planet is Mercury?

- Does Mercury Have Rings?

- How Many Moons Does Mercury Have?

Conditions on Mercury:

- Surface of Mercury

- Temperature of Mercury

- Color of Mercury

- How Hot is Mercury?

- Life on Mercury

- Atmosphere of Mercury

- Weather on Mercury

- Is There Ice on Mercury?

- Water on Mercury

- Geology of Mercury

- Mercury Magnetic Field

- Climate of Mercury

History of Mercury:

- How Old is Mercury?

- Discovery of Planet Mercury?

- Have Humans Visited Mercury?

- Exploration of Mercury

- Who Discovered Mercury?

- Missions to Mercury

- How Did Mercury Get its Name?

- Symbol for Mercury

Other Mercury Articles:

Faces of the Solar System

“Look, it has a tiny face on it!”

This sentiment was echoed ‘round the web recently, as an image of Pluto’s tiny moon Nix was released by the NASA New Horizons team. Sure, we’ve all been there. Lay back in a field on a lazy July summer’s day, and soon, you’ll see faces of all sorts in the puffy stratocumulus clouds holding the promise of afternoon showers.

This predilection is so hard-wired into our brains, that often our facial recognition software sees faces where there are none. Certainly, seeing faces is a worthy survival strategy; not only is this aspect of cognition handy in recognizing the friendlies of our own tribe, but it’s also useful in the reading of facial expressions by giving us cues of the myriad ‘tells’ in the social poker game of life.

And yes, there’s a term for the illusion of seeing faces in the visual static: pareidolia. We deal lots with pareidolia in astronomy and skeptical circles. As NASA images of brave new worlds are released, an army of basement bloggers are pouring over them, seeing miniature bigfoots, flowers, and yes, lots of humanoid figures and faces. Two craters and the gash of a trench for a mouth will do.

Now that new images of Pluto and its entourage of moons are pouring in, neural circuits ‘cross the web are misfiring, seeing faces, half-buried alien skeletons and artifacts strewn across Pluto and Charon. Of course, most of these claims are simply hilarious and easily dismissed… no one, for example, thinks the Earth’s Moon is an artificial construct, though its distorted nearside visage has been gazing upon the drama of humanity for millions of years.

The psychology of seeing faces is such that a whole region of the occipital lobe of the brain known as the fusiform face area is dedicated to facial recognition. We each have a unique set of neurons that fire in patterns to recognize the faces of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, and other celebs (thanks, internet).

Damage this area at the base of the brain or mess with its circuitry, and a condition known as prosopagnosia, or face blindness can occur. Author Oliver Sacks and actor Brad Pitt are just a few famous personalities who suffer from this affliction.

Conversely, ‘super-recognizers’ at the other end of the spectrum have a keen sense for facial identification that verges on a super-power. True story: my wife has just such a gift, and can immediately spot second-string actors and actresses in modern movies from flicks and television shows decades old.

It would be interesting to know if there’s a correlation between face blindness, super-recognition and seeing faces in the shadows and contrast on distant worlds… to our knowledge, no such study has been conducted. Do super-recognizers see faces in the shadowy ridges and craters of the solar system more or less than everyone else?

A well-known example was the infamous ‘Face on Mars.’ Imaged by the Viking 1 orbiter in 1976, this half in shadow image looked like a human face peering back up at us from the surface of the Red Planet from the Cydonia region.

But when is a face not a face?

Now, it’s not an entirely far-fetched idea that an alien entity visiting the solar system would place something (think the monolith on the Moon from Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey) for us to find. The idea is simple: place such an artifact so that it not only sticks out like a sore thumb, but also so it isn’t noticed until we become a space-faring society. Such a serious claim would, however, to paraphrase Carl Sagan, demand serious and rigorous evidence.

But instead of ‘Big NASA’ moving to cover up the ‘face,’ they did indeed re-image the region with both the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Global Surveyor at a much higher resolution. Though the 1.5 kilometer feature is still intriguing from a geological perspective… it’s now highly un-facelike in appearance.

Of course, it won’t stop the deniers from claiming it was all a big cover-up… but if that were the case, why release such images and make them freely available online? We’ve worked in the military before, and can attest that NASA is actually the most transparent of government agencies.

We also know the click bait claims of all sorts of alleged sightings will continue to crop up across the web, with cries of ‘Wake up, Sheeople!’ (usually in all caps) as a brave band of science-writing volunteers continue to smack down astro-pareidolia on a pro bono basis in battle of darkness and light which will probably never end.

What examples of astro-pareidolia have you come across in your exploits?

Mercury MESSENGER Mission Concludes with a Smashing Finale!

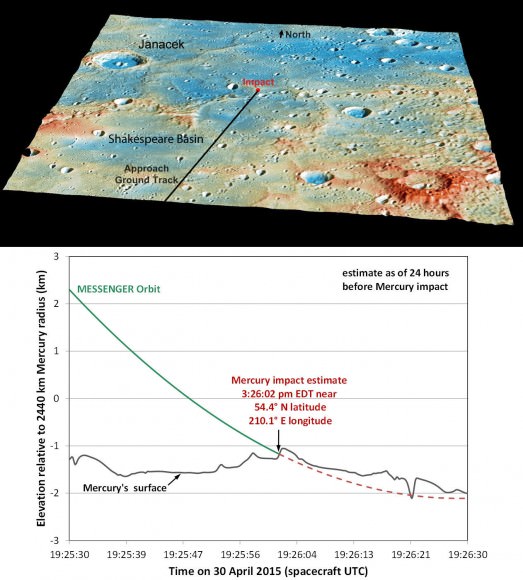

The planet Mercury has a brand new 52-foot-wide crater. At 3:26 p.m. EDT this afternoon, NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft bit the Mercurial dust, crashing into the planet’s surface at over 8,700 mph just north of the Shakespeare Basin. Because the impact happened out of sight and communication with the Earth, the MESSENGER team had to wait about 30 minutes after the predicted impact to announce the mission’s end.

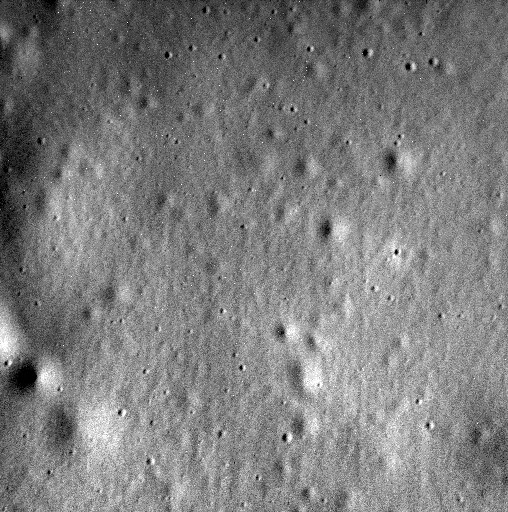

Even as MESSENGER faced its demise, it continued to take pictures and gather data right up until impact. The first-ever space probe to orbit the Solar System’s innermost planet, MESSENGER has completed 4,103 orbits as of this morning. Not only has it imaged the planet in great detail, but using it seven science instruments, scientists have gathered data on the composition and structure of Mercury’s crust, its geologic history, the nature of its magnetic field and rarefied sodium-calcium atmosphere, and the makeup of its iron core and icy materials near its poles.

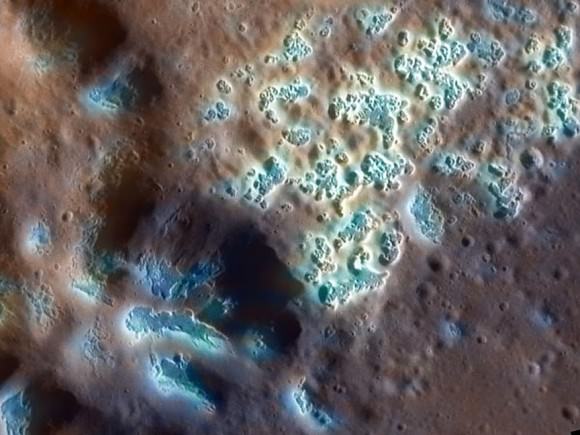

Images show those ubiquitous craters but also features that set its moonlike landscape apart from the Moon including volcanic plains, tectonic landforms that indicate the planet shrank as its interior cooled and mysterious mouse-like nibbles called “hollows”, where surface material may be vaporizing in sunlight leaving behind a network of holes. To learn more about the mission’s “greatest hits”, check out its Top Ten discoveries or pay a visit to the Gallery.

MESSENGER mission controllers conducted the last of six planned maneuvers on April 24 to raise the spacecraft’s minimum altitude sufficiently to extend orbital operations and further delay the probe’s inevitable impact onto Mercury’s surface, but it’s now out of propellant. Without the ability to counteract the Sun’s gravity, which is slowly pulling the craft closer to Mercury’s surface, the team prepared for the inevitable.

The spacecraft actually ran out of propellant a while back, but controllers realized they could re-purpose a stock of helium, originally carried to pressurize the fuel, for a few final blasts to keep it alive and doing science right up to the last minute. During its final hours today, MESSENGER will be shooting and sending back as many new pictures as possible the same way you’d squeeze in one last shot of the Grand Canyon before departing for home. It’s also holding hundreds of older photos in its memory chip and will send as many of those as it can before the final deadline.

“Operating a spacecraft in orbit about Mercury, where the probe is exposed to punishing heat from the Sun and the planet’s dayside surface as well as the harsh radiation environment of the inner heliosphere (Sun’s sphere of influence), would be challenge enough,” said Principal Investigator Sean Solomon, MESSENGER principal investigator. “But MESSENGER’s mission design, navigation, engineering, and spacecraft operations teams have fought off the relentless action of solar gravity, made the most of every usable gram of propellant, and devised novel ways to modify the spacecraft trajectory never before accomplished in deep space.”

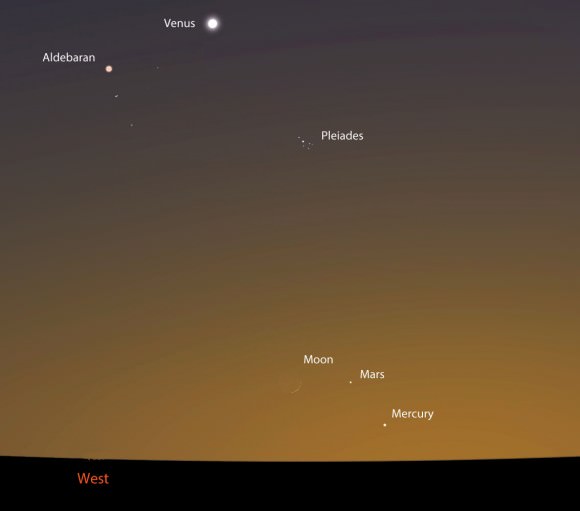

Ground-based telescopes won’t be able to spy MESSENGER’s impact crater because of its small size, but the BepiColombo Mercury probe, due to launch in 2017 and arrive in orbit at Mercury in 2024, should be able to get a glimpse. Speaking of spying, you can see the planet Mercury tonight (and for the next week or two), when it will be easily visible low in the northwestern sky starting about 45 minutes after sundown. The planet coincidentally makes its closest approach to the Pleiades star cluster tonight and tomorrow.

Use the occasion to wish MESSENGER a fond farewell.

Lunar ‘Fountain of Youth’ Challenge / Mercury Returns with Gusto

16th century Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León looked and looked but never did find the Fountain of Youth, a spring rumored to restore one’s youth if you bathed or drank from its waters. If he had, I might have interviewed him for this story.

Sunday night, another symbol of youth beckons skywatchers the world over. A fresh-faced, day-young crescent Moon will hang in the western sky in the company of the planets Mars and Mercury. While I can’t promise a wrinkle-free life, sighting it may send a tingle down your spine reminding you of why you fell in love with astronomy in the first place.

The Moon reaches New Moon phase on Saturday, April 18 during the early afternoon for North and South America. By sunset Sunday, the fragile crescent will be about 29 hours old as seen from the East Coast, 30 for the Midwest, 31 for the mountain states and 32 hours for the West Coast. Depending on where you live, the Moon will hover some 5-7° (three fingers held at arm’s length) above the northwestern horizon 40 minutes after sunset. To make sure you see it, find a location with a wide-open view to the west-northwest.

While the crescent is illuminated by direct sunlight, you’ll also see the full outline of the Moon thanks to earthshine. Sunlight reflected off Earth’s globe faintly illuminates the portion of the Moon not lit by the Sun. Because it’s twice-reflected, the light looks more like twilight. Ghostly. Binoculars will help you see it best.

Now that you’ve found the dainty crescent, slide your eyes (or binoculars) to the right. That pinpoint of light just a few degrees away is Mars, a planet that’s lingered in the evening sky longer than you’ve promised to clean out the garage. The Red Planet shone brightly at opposition last April but has since faded and will soon be in conjunction with the Sun. Look for it to return bigger and brighter next May when it’s once again at opposition.

To complete the challenge, you’ll have to look even lower in the west to spot Mercury. Although brighter than Vega, it’s only 3° high 40 minutes after sunset Sunday. Its low altitude makes it Mercury is only just returning to the evening sky in what will become its best appearance at dusk for northern hemisphere skywatchers in 2015.

Right now, because of altitude, the planet’s a test of your sky and observing chops, but let the Moon be your guide on Sunday and you might be surprised. In the next couple weeks, Mercury vaults from the horizon, becoming easier and easier to see. Greatest elongation east of the Sun occurs on the evening of May 6. Although the planet will be highest at dusk on that date, it will have faded from magnitude -0.5 to +1.2. By the time it leaves the scene in late May, it will become very tricky to spot at magnitude +3.5.

Mercury’s a bit different from Venus, which is brighter in its crescent phase and faintest at “full”. Mercury’s considerably smaller than Venus and farther from the Earth, causing it to appear brightest around full phase and faintest when a crescent, even though both planets are largest and closest to us when seen as crescents.

Venus makes up for its dwindling girth by its size and close proximity to Earth. It also doesn’t hurt that it’s covered in highly reflective clouds. Venus reflects about 70% of the light it receives from the Sun; Mercury’s a dark world and gives back just 7%. That’s dingier than the asphalt-toned Moon!

Good luck in your mercurial quest. We’d love to hear your personal stories of the hunt — just click on Comments.

The End is Near: NASA’s MESSENGER Now Running on Fumes

For more than four years NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft has been orbiting our solar system’s innermost planet Mercury, mapping its surface and investigating its unique geology and planetary history in unprecedented detail. But the spacecraft has run out of the fuel needed to maintain its extremely elliptical – and now quite low-altitude – orbit, and the Sun will soon set on the mission when MESSENGER makes its fatal final dive into the planet’s surface at the end of the month.

On April 30 MESSENGER will impact Mercury, falling down to its Sun-baked surface and colliding at a velocity of 3.9 kilometers per second, or about 8,700 mph. The 508-kilogram spacecraft will create a new crater on Mercury about 16 meters across.

The impact is estimated to occur at 19:25 UTC, which will be 3:25 p.m. at the John Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, Maryland, where the MESSENGER operations team is located. Because the spacecraft will be on the opposite side of Mercury as seen from Earth the impact site will not be in view.

Postcards from the (Inner) Edge: MESSENGER Images of Mercury

But while it’s always sad to lose a dutiful robotic explorer like MESSENGER, its end is bittersweet; the mission has been more than successful, answering many of our long-standing questions about Mercury and revealing features of the planet that nobody even knew existed. The data MESSENGER has returned to Earth – over ten terabytes of it – will be used by planetary scientists for decades in their research on the formation of Mercury as well as the Solar System as a whole.

“For the first time in history we now have real knowledge about the planet Mercury that shows it to be a fascinating world as part of our diverse solar system,” said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “While spacecraft operations will end, we are celebrating MESSENGER as more than a successful mission. It’s the beginning of a longer journey to analyze the data that reveals all the scientific mysteries of Mercury.”

View the top ten science discoveries from MESSENGER here.

On April 6 MESSENGER used up the last vestiges of the liquid hydrazine propellant in its tanks, which it needed to make course corrections to maintain its orbit. But the tanks also hold gaseous helium as a pressurizer, and system engineers figured out how to release that gas through the complex hydrazine nozzles and keep MESSENGER in orbit for a few more weeks.

On April 24, though, even those traces of helium will be exhausted after a sixth and final orbit correction maneuver. From that point on MESSENGER will be coasting – out of fuel, out of fumes, and out of time.

“Following this last maneuver, we will finally declare MESSENGER out of propellant, as this maneuver will deplete nearly all of our remaining helium gas,” said Mission Systems Engineer Daniel O’Shaughnessy. “At that point, the spacecraft will no longer be capable of fighting the downward push of the Sun’s gravity.

“After studying the planet intently for more than four years, MESSENGER’s final act will be to leave an indelible mark on Mercury, as the spacecraft heads down to an inevitable surface impact.”

Read more: Five Mercury Secrets Revealed by MESSENGER

But MESSENGER scientists and engineers can be proud of the spacecraft that they built, which has proven itself more than capable of operating in the inherently challenging environment so close to our Sun.

“MESSENGER had to survive heating from the Sun, heating from the dayside of Mercury, and the harsh radiation environment in the inner heliosphere, and the clearest demonstration that our innovative engineers were up to the task has been the spacecraft’s longevity in one of the toughest neighborhoods in our Solar System,” said MESSENGER Principal Investigator Sean Solomon. “Moreover, all of the instruments that we selected nearly two decades ago have proven their worth and have yielded an amazing series of discoveries about the innermost planet.”

The MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) spacecraft launched on August 3, 2004, and traveled over six and a half years before entering orbit about Mercury on March 18, 2011 – the first spacecraft ever to do so. Learn more about the mission’s many discoveries here.

The video below was released in 2013 to commemorate MESSENGER’s second year in orbit and highlights some of the missions important achievements.

Source: NASA and JHUAPL

Are you an educator? Check out some teaching materials and shareables on the MESSENGER community page here.