[/caption]

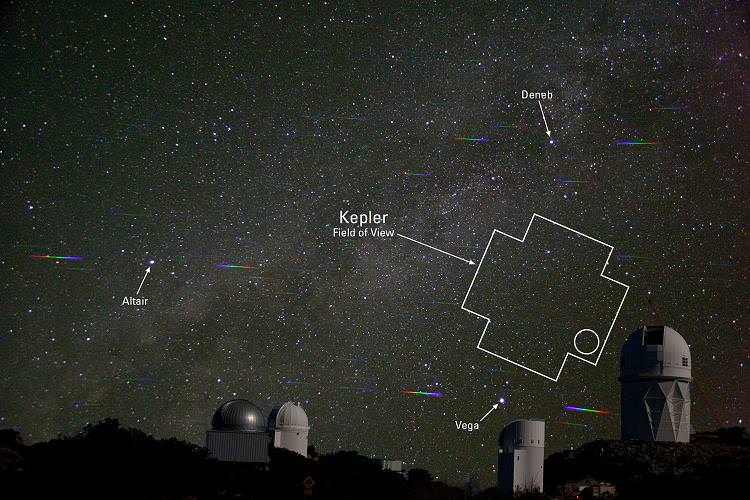

December 2011 will go down in history as the first time humanity was able to detect an Earth-sized planet around another Sun-like star, said Francois Fressin, an astronomer from Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Fressin and his team used the Kepler planet-hunting spacecraft to find two rocky worlds – one just a bit bigger than Earth and the other slightly smaller than Venus.

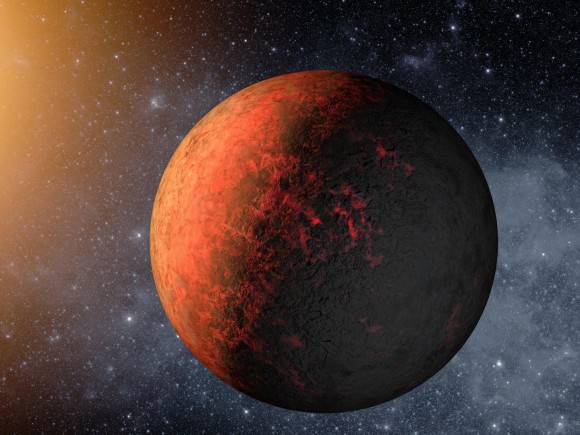

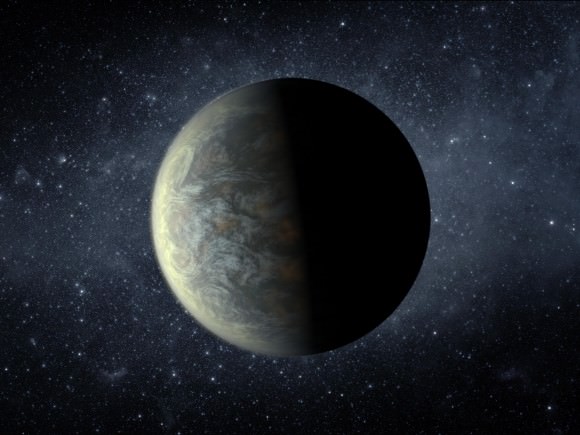

The two planets, named Kepler-20e and 20f, are the smallest planets found to date. They have diameters of 11,000 km (6,900 miles) and 13,190 km (8,200 miles) – equivalent to 0.87 and 1.03 times Earth. Astronomers expect these worlds to have rocky compositions, so their masses should be less than 1.7 and 3 times Earth’s.

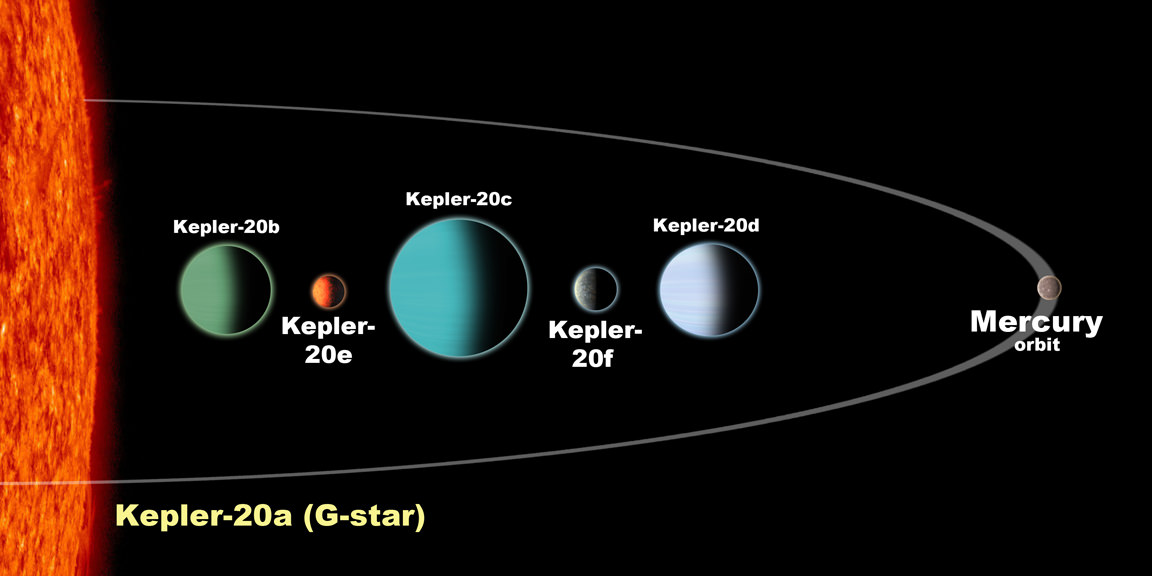

The two worlds are part of a multiple-planet system with five planets around the same star, and is located about 1,000 light years away in the constellation of Lyra. “People can point to that area in the sky and say this is where the era of exo-Earth’s began,” said Fressin, adding that the two rocky worlds are too close to their star — and thus too hot — to be habitable.

Kepler-20e orbits every 6.1 days at a distance of 4.7 million miles. Kepler-20f orbits every 19.6 days at a distance of 10.3 million miles. Due to their tight orbits, they are heated to temperatures of 760 Celcius (1,400 degrees Fahrenheit) and 426 C (800 degrees F.)

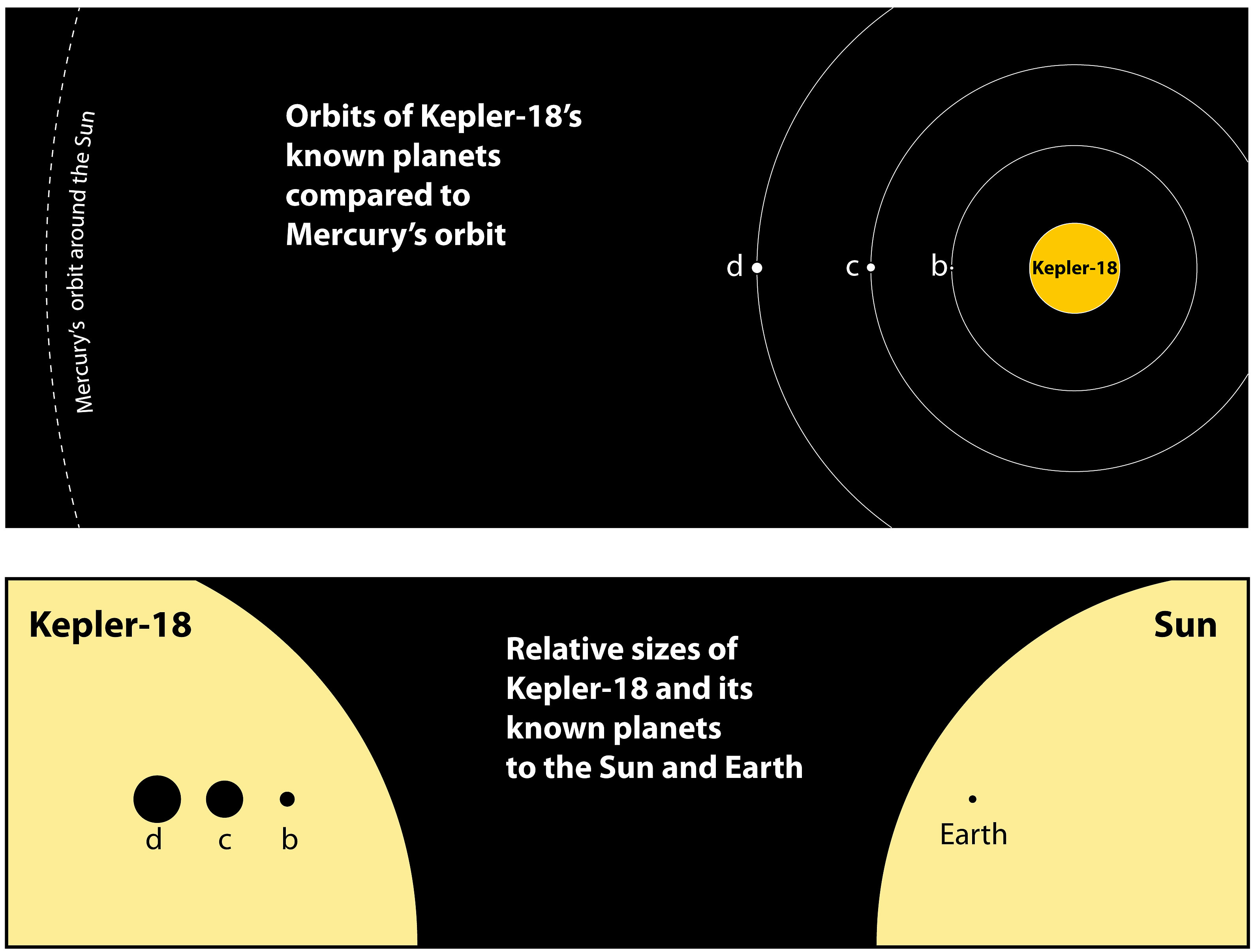

The solar system where these planets exists is quite unusual, where rocky and gas planets alternate in their positions instead of being separated into groups like in our own solar system.

The first planet is a Neptune-like world; then the first rocky planet, Kepler 20e; next is another Neptune world; following is the next rocky world 20f, and then another Neptune-like gas planet.

“So, big, little, big, little, big — which is unlike any other system so far,” said David Charbonneau, from Harvard University. “We were surprised to find this system of flip-flopping planets. It’s very different than our solar system.”

Additionally, all the planets are very closely compact, lying within the orbit of Mercury around our Sun.

This unusual system of alternating planets may not be unusual at all, as our sample of solar systems is still relatively small.

“This really is a problem for our community to explain,” said Linda Elkins-Tanton, director of the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism in Washington, in response to a question posed by Universe Today about the dynamics of such a system. “We are really challenging the community for the reason why this happened, and it may well be that our solar system may be in the minority.”

The astronomers don’t think the planets of Kepler-20 formed in their current locations. Instead, they must have formed farther from their star and then migrated inward, probably through interactions with the disk of material from which they all formed. This allowed the worlds to maintain their regular spacing despite alternating sizes.

“We think they migrated because we can’t imagine all this stuff so close to the star, where it is warm and only portions of the material is in solid form,” Charbonneau told Universe Today. “We think the birth place of a Neptune-like world is farther from the star and then over time the planets migrate in. Wouldn’t be surprised if we see more systems like this as we keep exploring.”

Asked when the Kepler team might find a “best of both worlds” planet — one that is the right size and in the right place to be habitable, Nick Gautier, Kepler project scientist said they may find one in the next year or two, but the Kepler mission may need an extension to ensure finding the Holy Grail of exoplanets — one that is just like Earth.

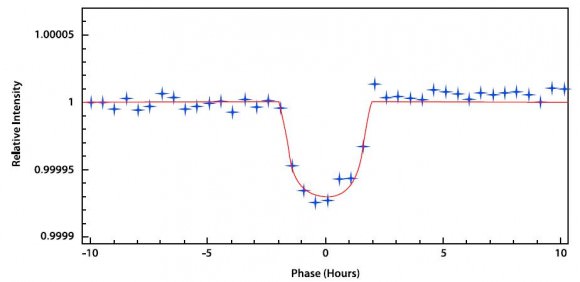

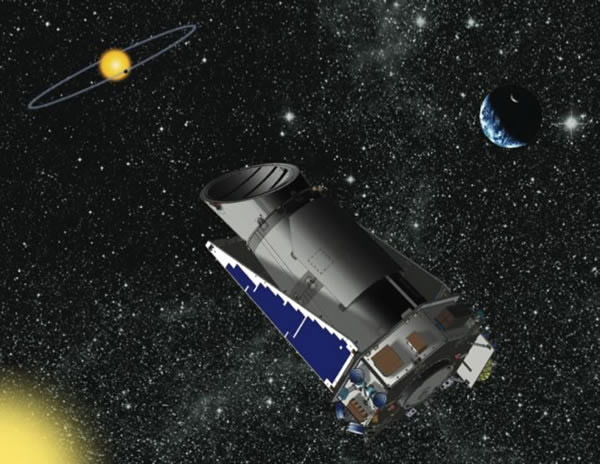

Kepler identifies “objects of interest” by looking for stars that dim slightly, which can occur when a planet crosses the star’s face. To confirm a transiting planet, astronomers look for the star to wobble as it is gravitationally tugged by its orbiting companion (a method known as radial velocity).

The radial velocity signal for planets weighing one to a few Earth masses is too small to detect with current technology. Therefore, other techniques must be used to validate that an object of interest is truly a planet.

A variety of situations could mimic the dimming from a transiting planet. For example, an eclipsing binary-star system whose light blends with the star Kepler-20 would create a similar signal. To rule out such imposters, the team simulated millions of possible scenarios with Blender – custom software developed by Fressin and Willie Torres of CfA. They concluded that the odds are strongly in favor of Kepler-20e and 20f being planets.

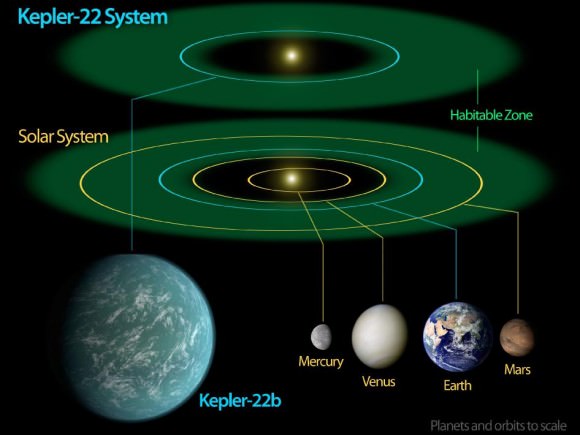

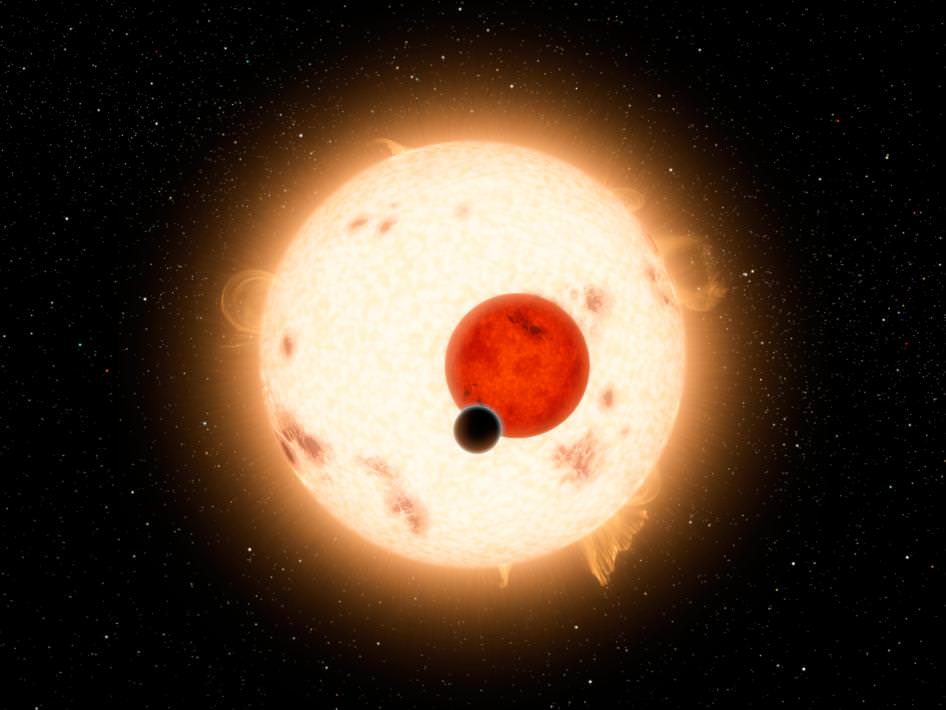

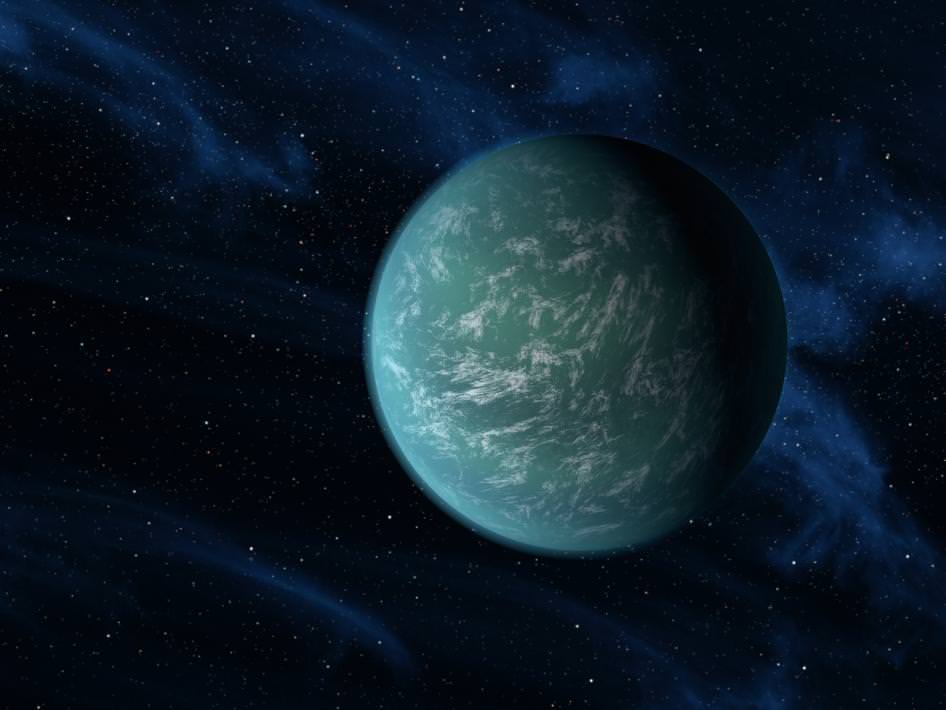

Fressin and Torres also used Blender to confirm the existence of Kepler-22b, a planet in the habitable zone of its star that was announced by NASA earlier this month. However, that world was much larger than Earth.

“These new planets are significantly smaller than any planet found up till now orbiting a Sun-like star,” added Fressin.

For further reading:

It was also announced that Kepler has found 1,094 more planetary candidates, increasing the number now to 2,326! That’s an increase of 89% since the last update this past February. Of these, 207 are near Earth size, 680 are super-Earth size, 1,181 are Neptune size, 203 are Jupiter size and 55 are larger than Jupiter. These findings continue the observational trend seen before, where smaller planets are apparently more numerous than larger gas giant planets. The number of Earth size candidates has increased by more than 200 percent and the number of super-Earth size candidates has increased by 140 percent.

It was also announced that Kepler has found 1,094 more planetary candidates, increasing the number now to 2,326! That’s an increase of 89% since the last update this past February. Of these, 207 are near Earth size, 680 are super-Earth size, 1,181 are Neptune size, 203 are Jupiter size and 55 are larger than Jupiter. These findings continue the observational trend seen before, where smaller planets are apparently more numerous than larger gas giant planets. The number of Earth size candidates has increased by more than 200 percent and the number of super-Earth size candidates has increased by 140 percent.