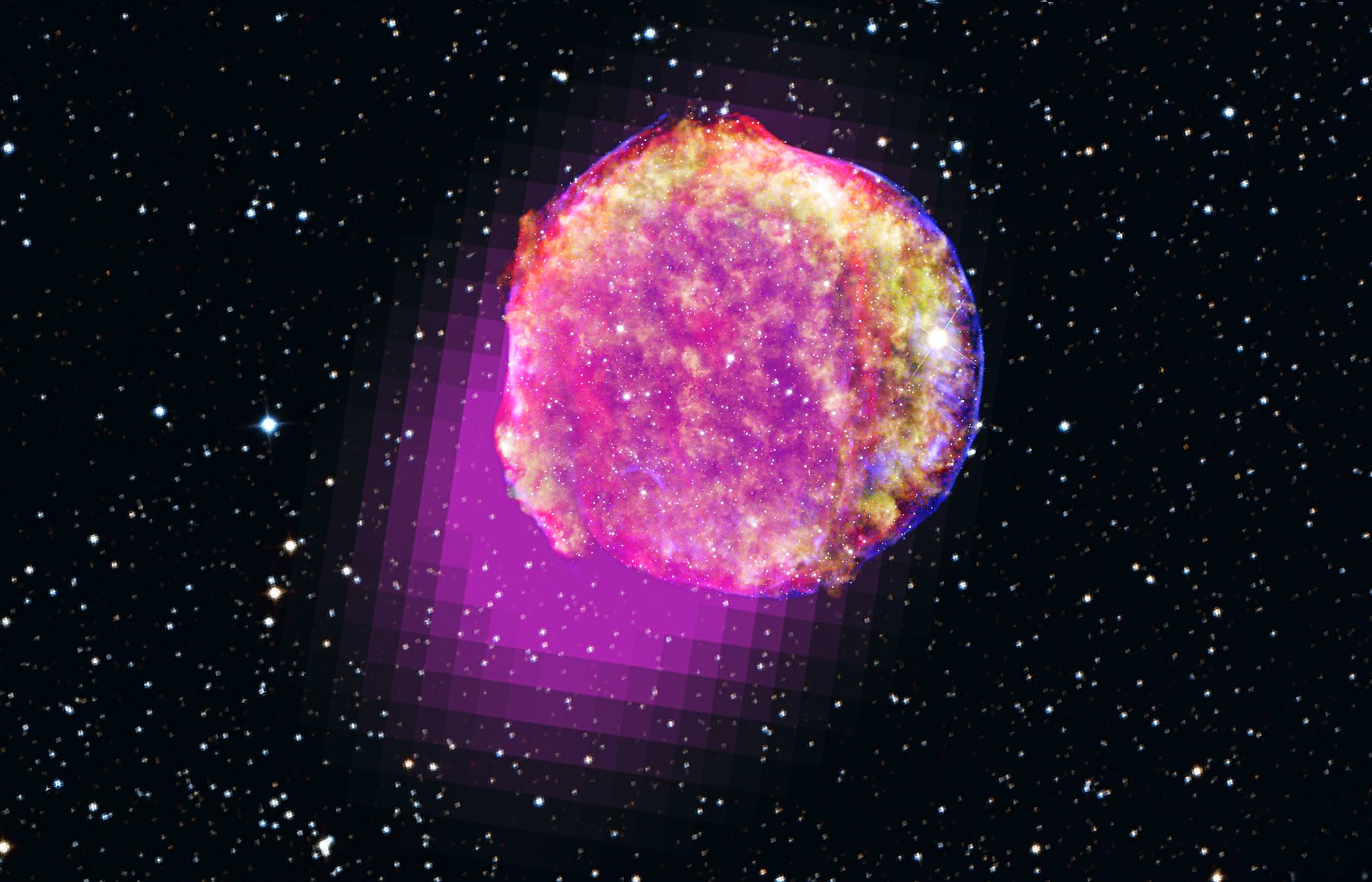

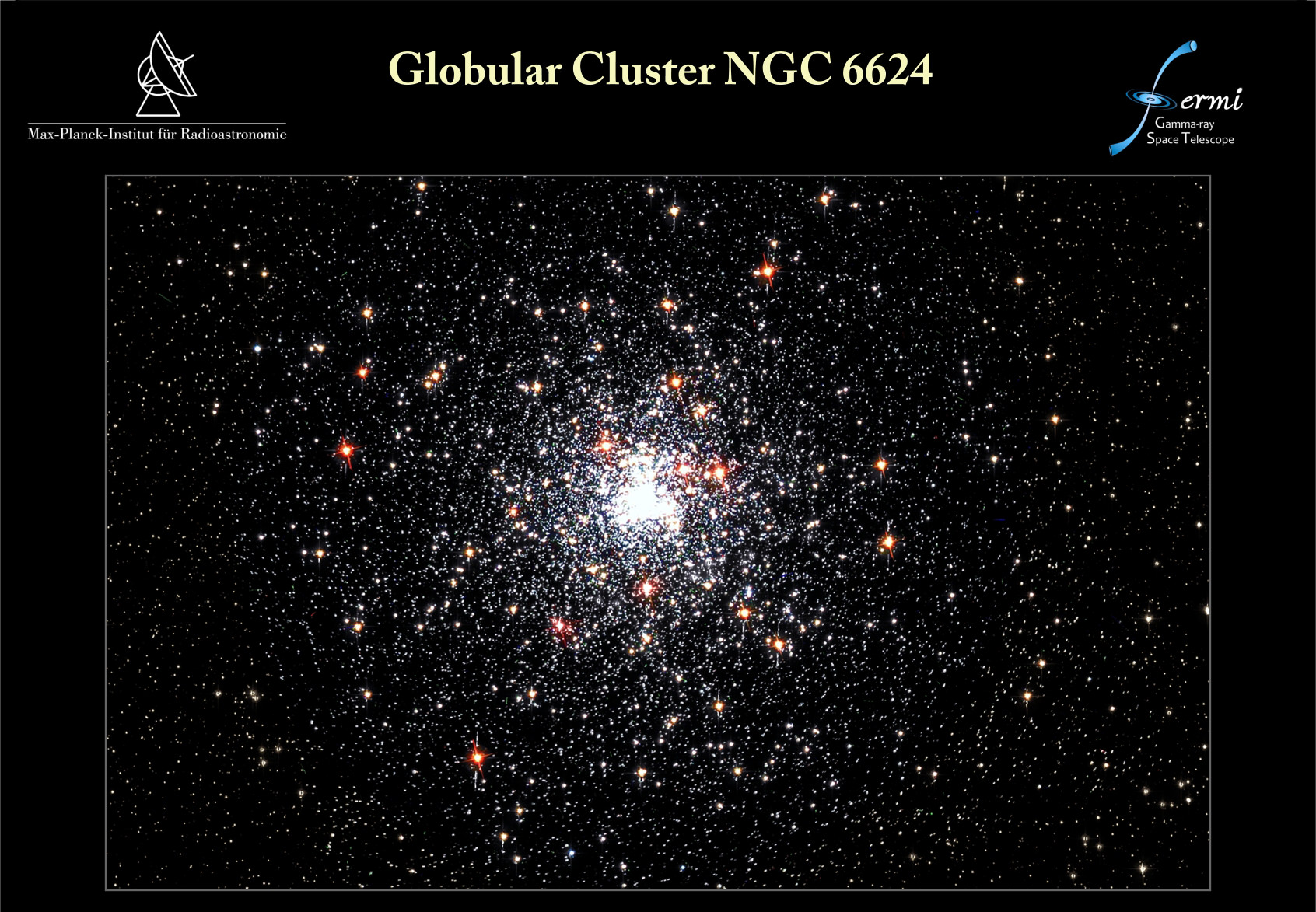

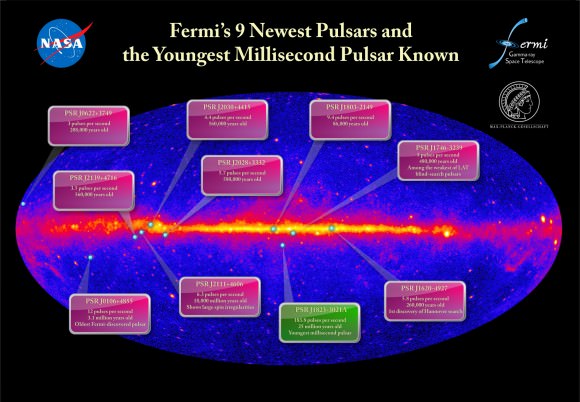

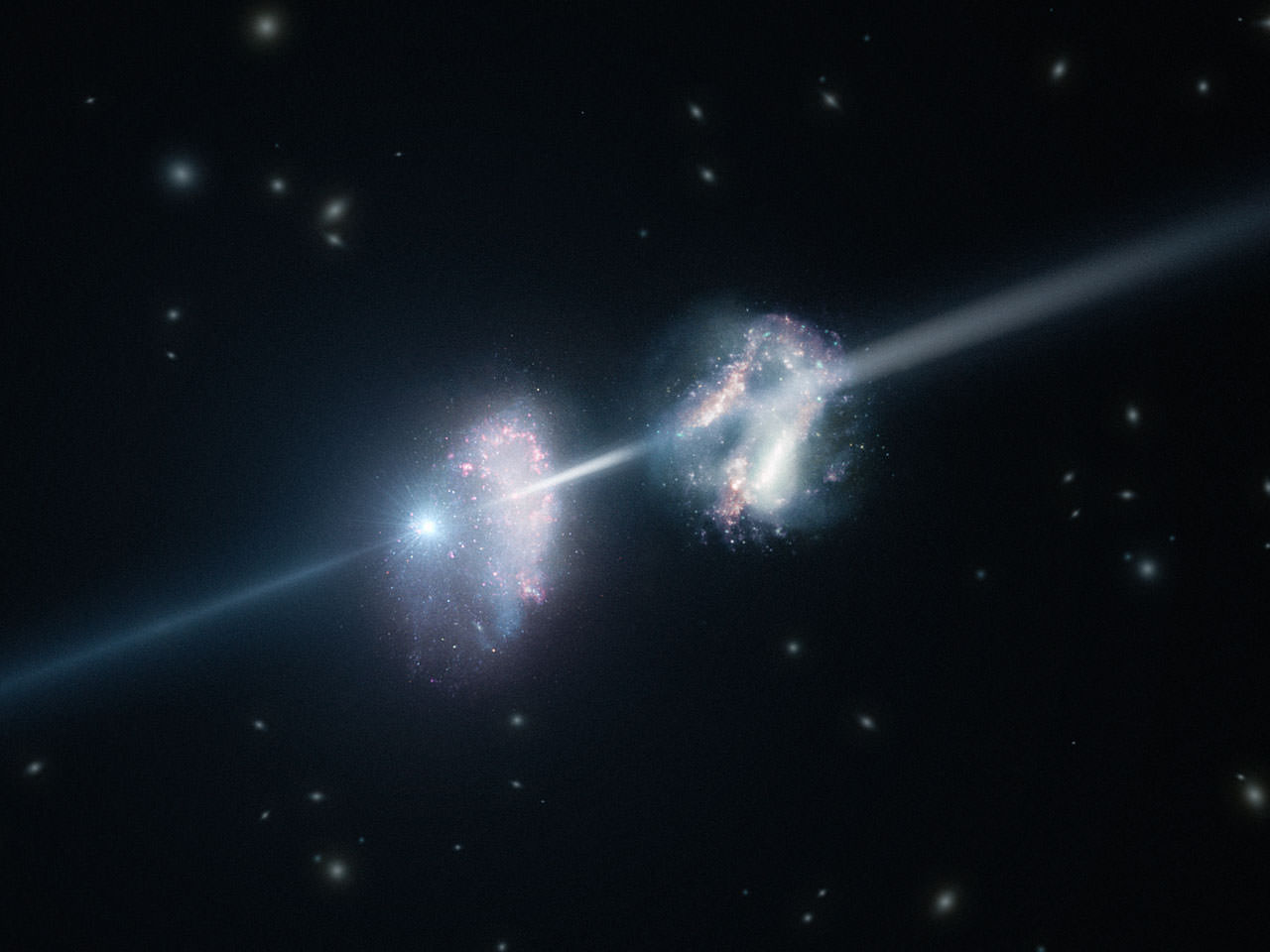

Researchers using the Large Area Telescope onboard the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope have developed a new method to detect a special class of stellar remnant, known as pulsars. A pulsar is a special type of neutron star, which spin hundreds of times per second. When the intense spin is combined with beams of energy caused by intense magnetic fields, a “lighthouse” pulse is generated. When the “lighthouse” beam sweeps across Earth’s field of view, the object is referred to as a pulsar.

Led by Matthew Kerr (Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology), and Fernando Camilo (Columbia University), a research team recently announced a new method for detecting pulsars. How will Kerr’s research help astronomers better understand (and locate) these small, elusive stellar remnants?

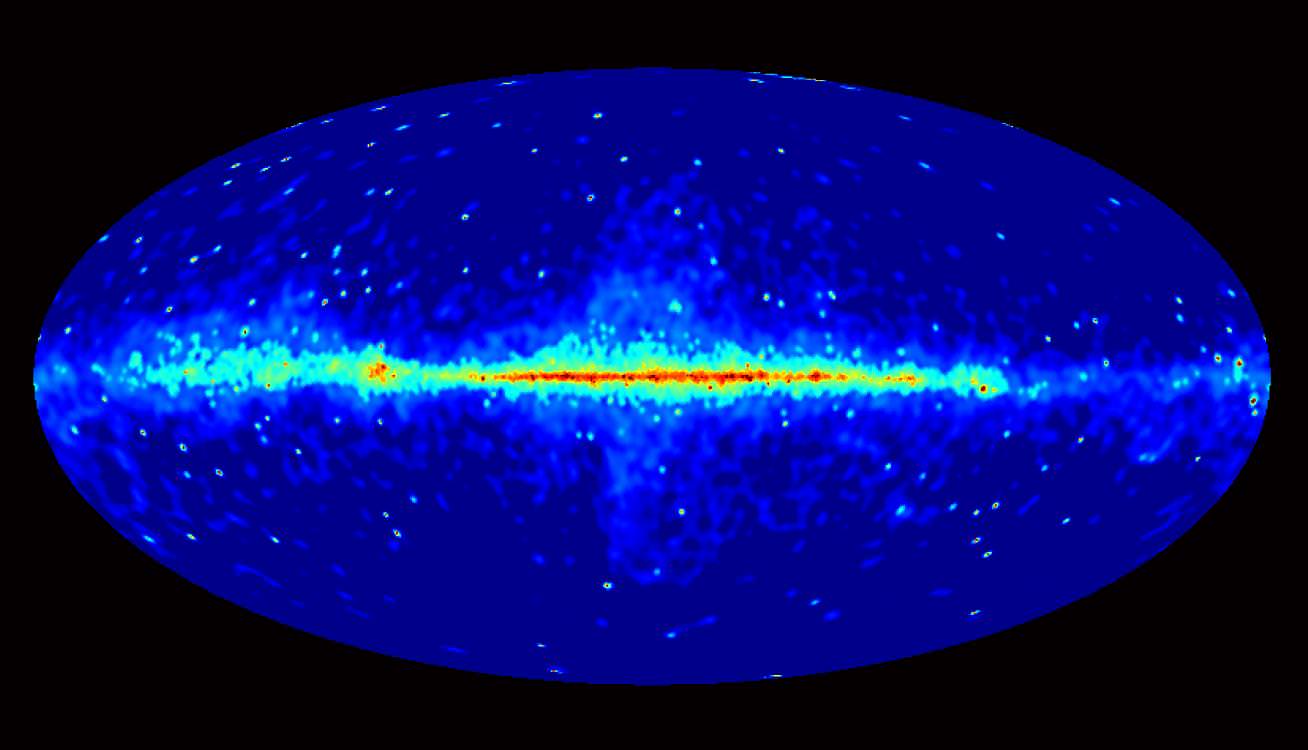

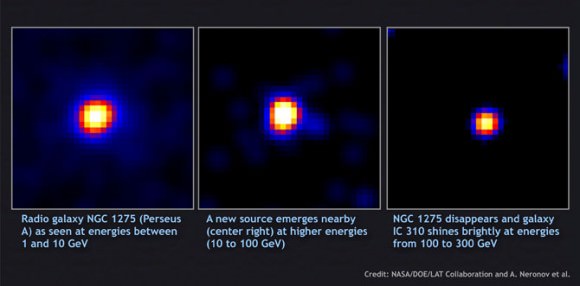

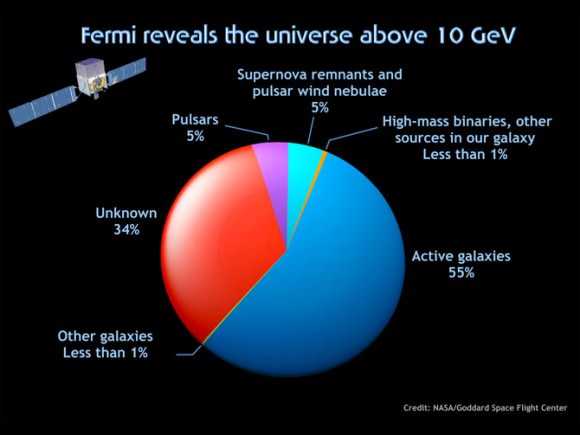

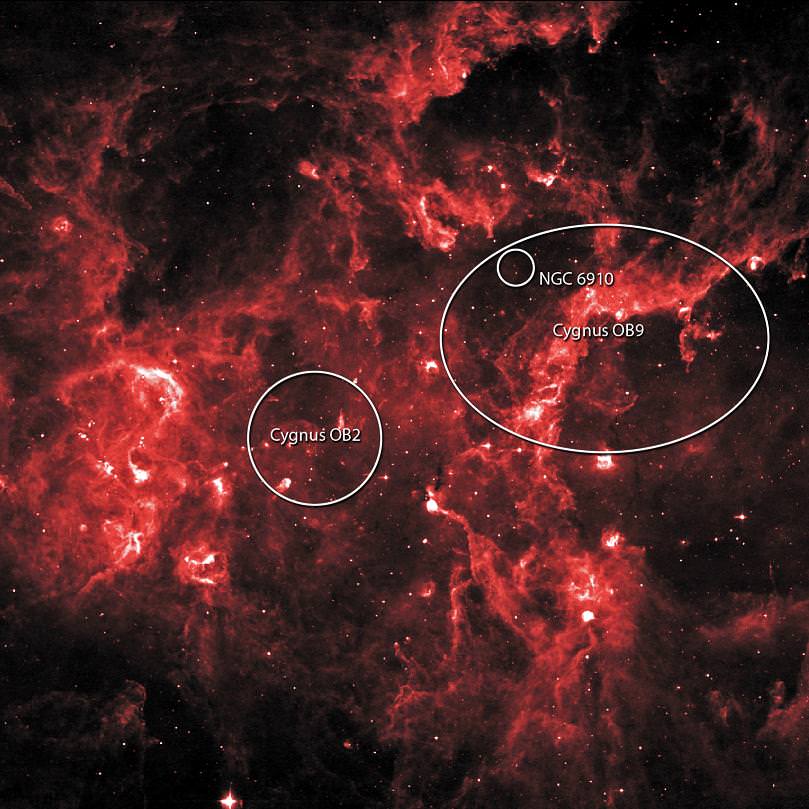

Every three hours, the LAT surveys the entire sky, searching for the high energy signatures associated with gamma-ray outbursts. In general the energy levels of the photos detected by the LAT are 20 million to over 300 billion times as energetic as the photons associated with visible light.

By combining observations from the LAT and data obtained from the Parkes radio telescope in Australia, the team is able to detect pulsar candidates. The team’s approach combines a “wide area” approach of an all-sky telescope like the LAT with the sensitivity of a radio telescope. So far, the team’s discovery of five “millisecond” class pulsars, including one unusual pulsar has proven their technique to be successful.

The unusual pulsar, officially named PSR J0101–6422, had an additional 35 days of study devoted to better understanding its properties. Once the radio pulsation period and phase were determined, an incredible amount of data, including data on its gamma-ray pulsations was obtained. Using the data, the team was able to determine PSR J0101–6422 is roughly 1750 light-years away from Earth, and has an unusual light curve which features a “sandwich” of two gamma-ray peaks with an intense radio peak in the center, like a cosmic ham sandwich.

The team was unable to explain the phenomenon with standard pulsar emission models.which the team could not explain with standard geometric pulsar emission models, and have proposed that J0101–6422 is a new hybrid class of pulsar that features radio emissions that originate from low and high altitudes above the neutron star.

If you’d like to learn more about the Fermi Gamma-ray space telescope, visit: http://fermi.gsfc.nasa.gov/

The results of Kerr’s research have been published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Image #1 Caption:Clouds of charged particles move along the pulsar’s magnetic field lines (blue) and create a lighthouse-like beam of gamma rays (purple) in this illustration. Image Credit: NASA