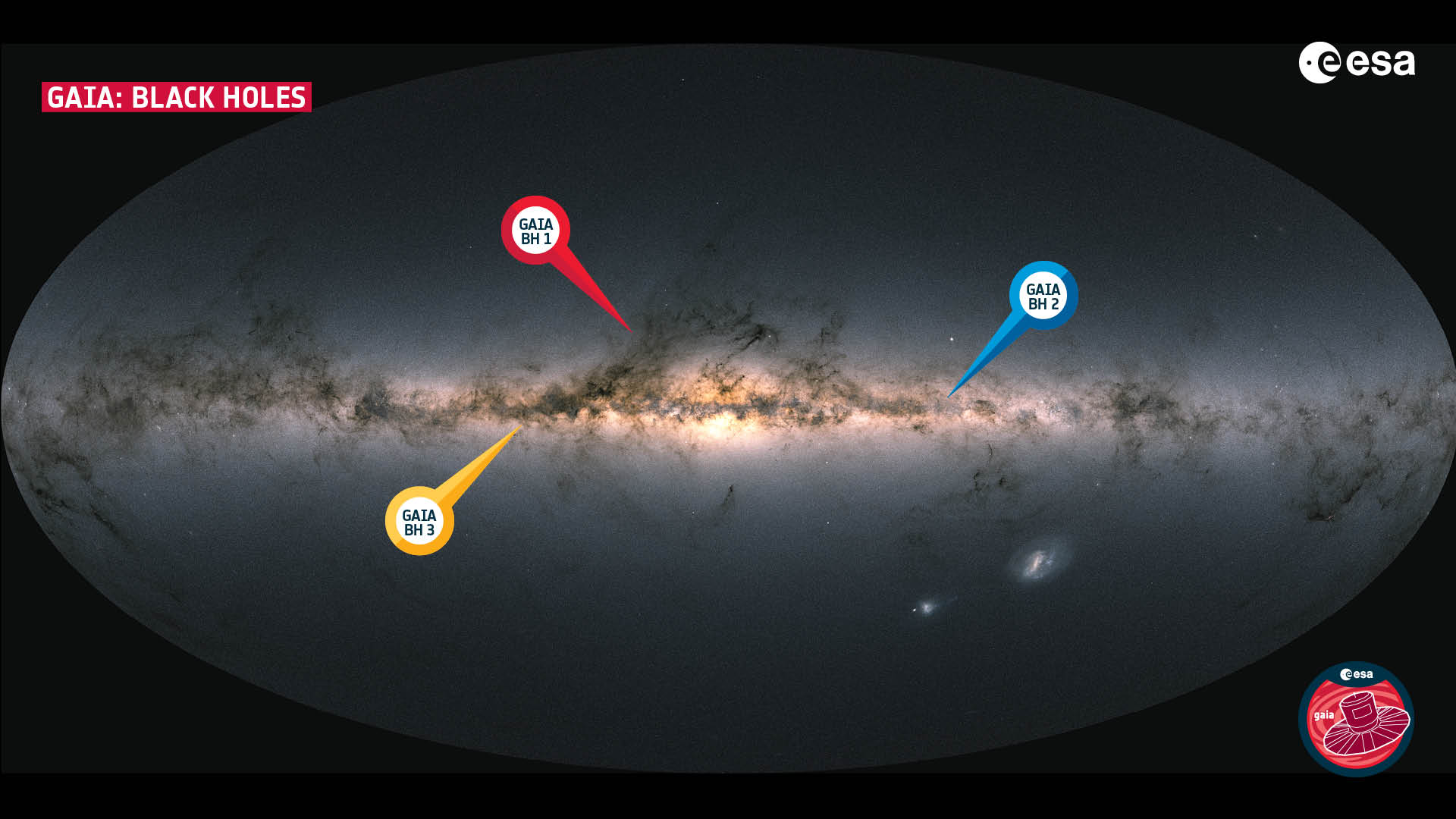

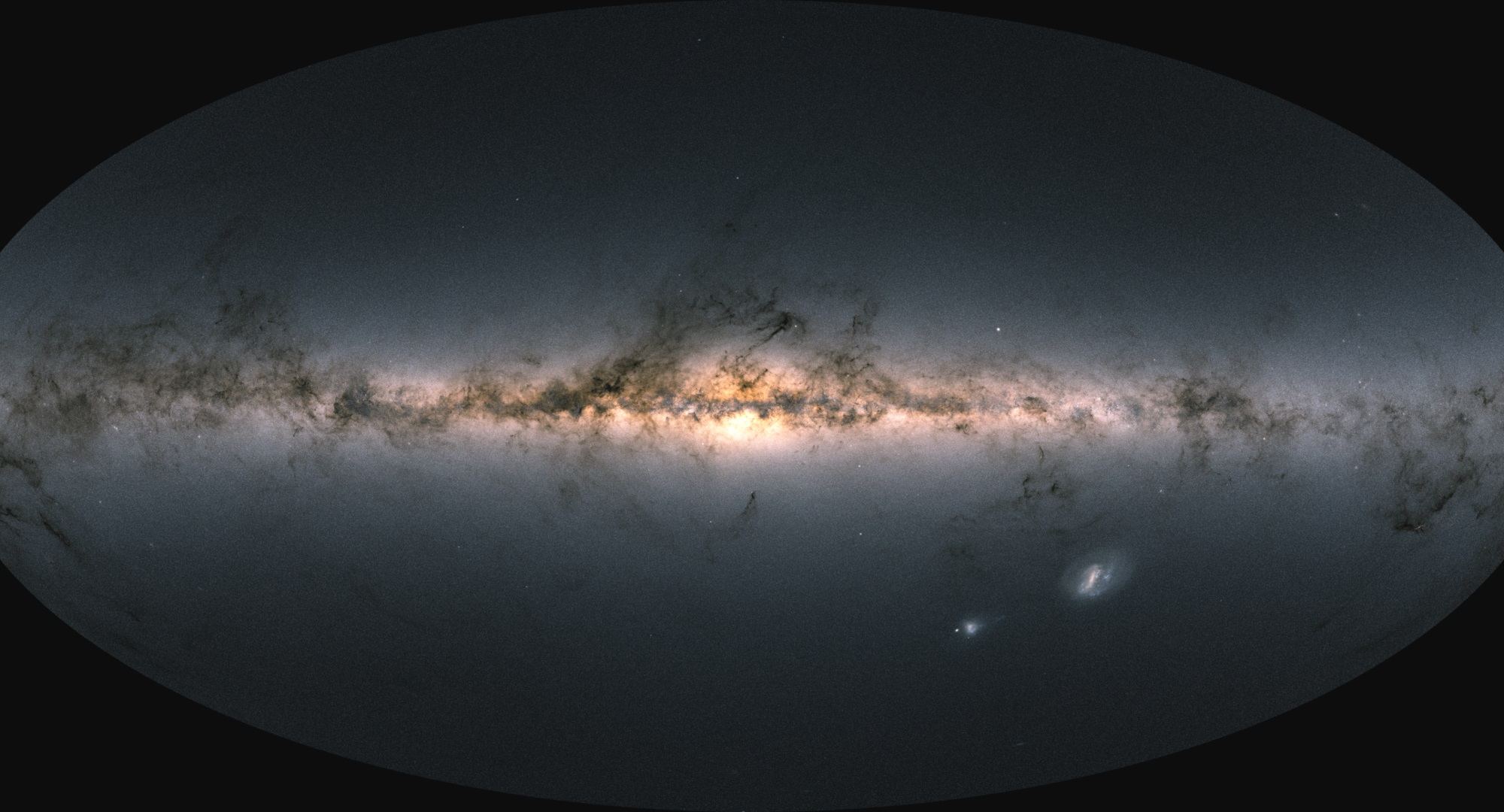

The ESA’s Gaia Observatory continues its astrometry mission, which consists of measuring the positions, distances, and motions of stars (and the positions of orbiting exoplanets) with unprecedented precision. Launched in 2013 and with a five-year nominal mission (2014-2019), the mission is expected to remain in operation until 2025. Once complete, the mission data will be used to create the most detailed 3D space catalog ever, totaling more than 1 billion astronomical objects – including stars, planets, comets, asteroids, and quasars.

Another benefit of this data, according to a team of researchers led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), is the ability to predict future microlensing events. Similar to gravitational lensing, this phenomenon occurs when light from background sources is deflected and amplified by foreground objects. Using information from Gaia‘s third data release (DR3), the team predicted 4500 microlensing events, 1664 of which are unlike any we have seen. These events will allow astronomers to conduct lucrative research into distant star systems, exoplanets, and other celestial objects.

Continue reading “Gaia is so Accurate it Can Predict Microlensing Events”