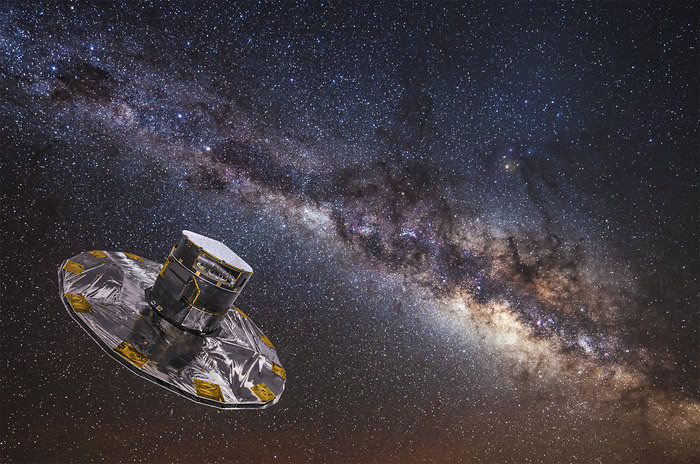

Early on the morning of Dec. 19, 2013, the pre-dawn sky above the coastal town of Kourou in French Guiana was briefly sliced by the brilliant exhaust of a Soyuz VS06 rocket as it ferried ESA’s “billion-star surveyor” Gaia into space, on its way to begin a five-year mission to map the precise locations of our galaxy’s stars. From its position in orbit around L2 Gaia will ultimately catalog the positions of over a billion stars… and in the meantime it will also locate a surprising amount of Jupiter-sized exoplanets – an estimated 21,000 by the end of its primary mission in 2019.

And, should Gaia continue observations in extended missions beyond 2019 improvements in detection methods will likely turn up even more exoplanets, anywhere from 50,000 to 90,000 over the course of a ten-year mission. Gaia could very well far surpass NASA’s Kepler spacecraft for exoplanet big game hunting!

“It is not just the number of expected exoplanet discoveries that is impressive”, said former mission project scientist Michael Perryman, lead author on a report titled Astrometric Exoplanet Detection with Gaia. “This particular measurement method will give us planet masses, a complete exoplanet survey around all types of stars in our Galaxy, and will advance our knowledge of the existence of massive planets orbiting far out from their host stars”.

Watch: ESA’s Gaia Launches to Map the Milky Way

The planets Gaia will be able to spot are expected to be anywhere from 1 to fifteen times the mass of Jupiter in orbit around Sun-like stars out to a distance of about 500 parsecs (1,630 light-years) from our own Solar System. Exoplanets orbiting smaller red dwarf stars will also be detectable, but only within about a fifth of that distance.

While other space observatories like NASA’s Kepler and CNES/ESA’s CoRoT were designed to detect exoplanets through the transit method, whereby a star’s brightness is dimmed ever-so-slightly by the silhouette of a passing planet, Gaia will detect particularly high-mass exoplanets by the gravitational wobble they impart to their host stars as they travel around them in orbit. This is known as the astrometric method.

A select few of those exoplanets will also be transiting their host stars as seen from Earth – anywhere from 25 to 50 of them – and so will be observable by Gaia as well as from many ground-based transit-detection observatories.

Read more: Gaia is “Go” for Science After a Few Minor Hiccups

After some issues with stray light sneaking into its optics, Gaia was finally given the green light to begin science observations at the end of July and has since been diligently scanning the stars from L2, 1.5 million km from Earth.

With the incredible ability to measure the positions of a billion stars each to an accuracy of 24 microarcseconds – that’s like measuring the width of a human hair from 1,000 km – Gaia won’t be “just” an unprecedented galactic mapmaker but also a world-class exoplanet detector! Get more facts about the Gaia mission here.

The team’s findings have been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Source: ESA