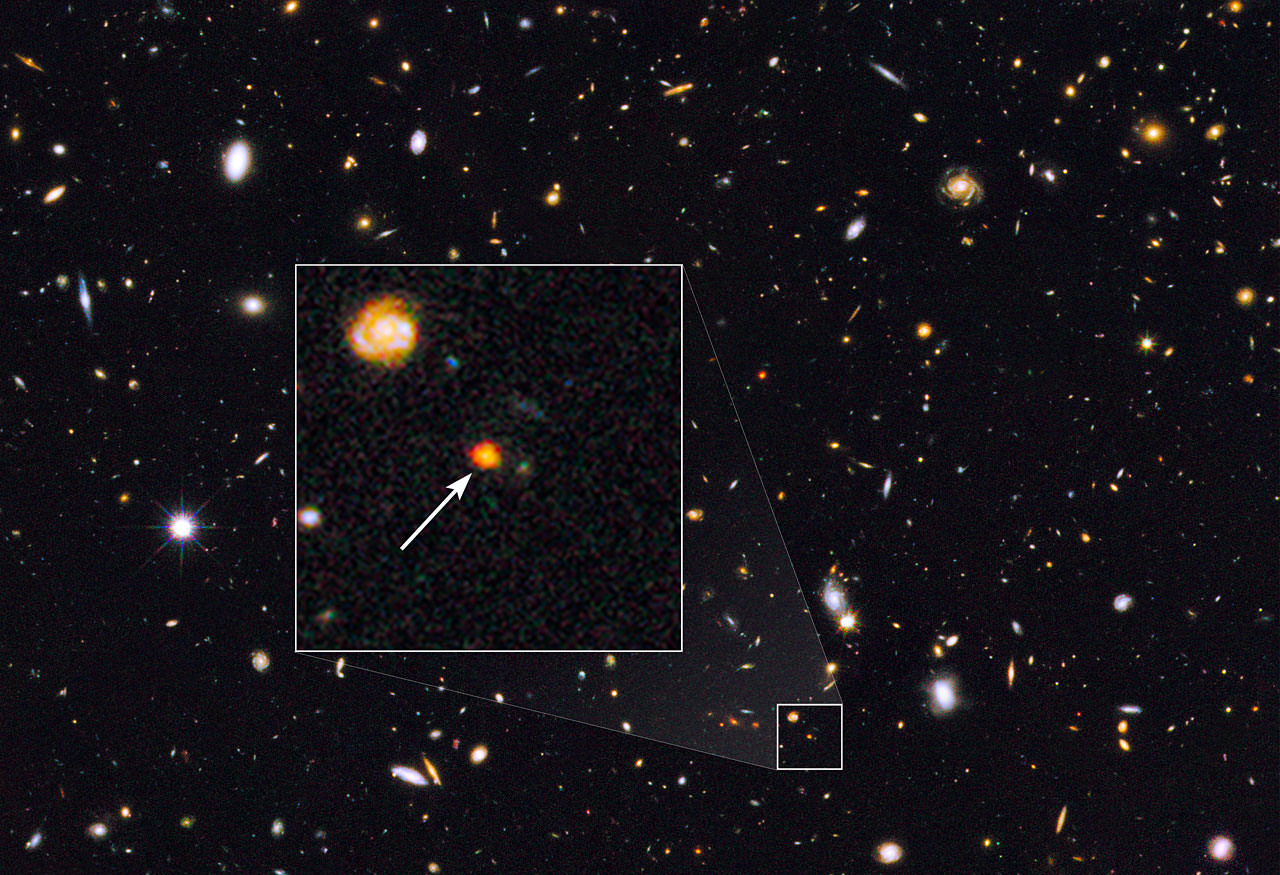

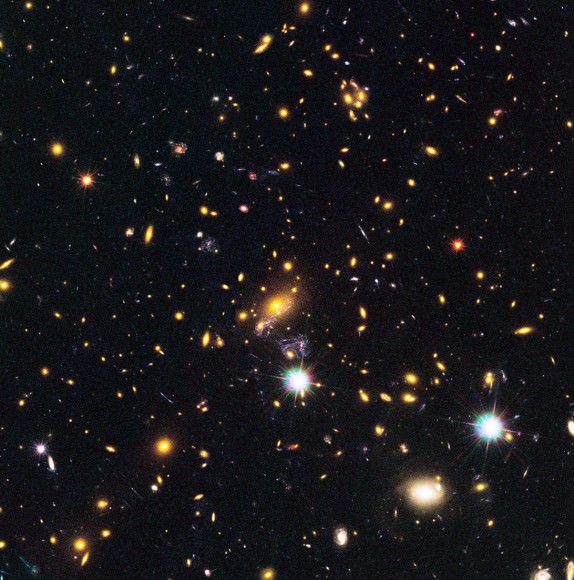

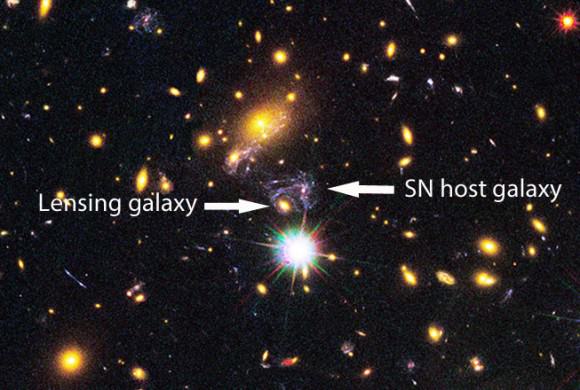

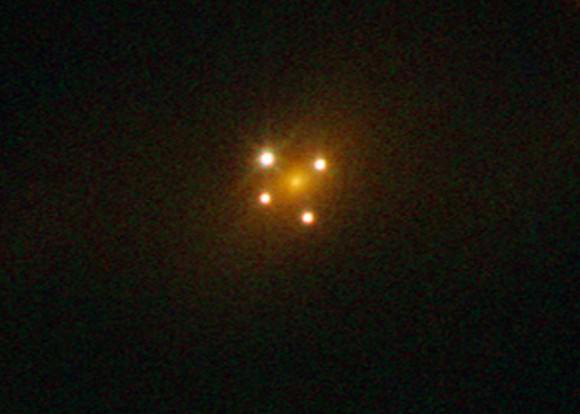

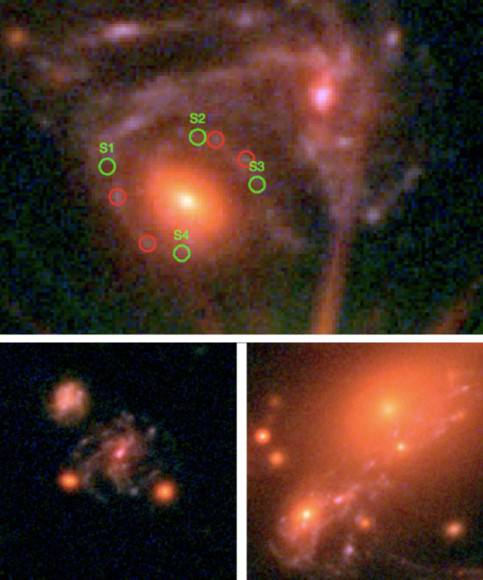

How about four supernovae for the price of one? Using the Hubble Space Telescope, Dr. Patrick Kelly of the University of California-Berkeley along with the GLASS (Grism Lens Amplified Survey from Space) and Hubble Frontier Fields teams, discovered a remote supernova lensed into four copies of itself by the powerful gravity of a foreground galaxy cluster. Dubbed SN Refsdal, the object was discovered in the rich galaxy cluster MACS J1149.6+2223 five billion light years from Earth in the constellation Leo. It’s the first multiply-lensed supernova every discovered and one of nature’s most exotic mirages.

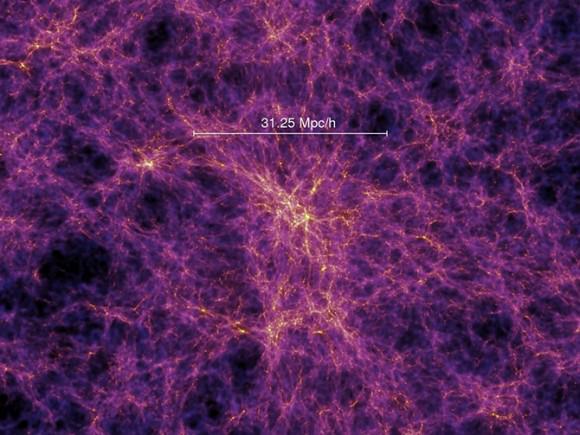

Gravitational lensing grew out of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity wherein he predicted massive objects would bend and warp the fabric of spacetime. The more massive the object, the more severe the bending. We can picture this by imagining a child standing on a trampoline, her weight pressing a dimple into the fabric. Replace the child with a 200-pound adult and the surface of the trampoline sags even more.

Similarly, the massive Sun creates a deep, but invisible dimple in the fabric of spacetime. The planets feel this ‘curvature of space’ and literally roll toward the Sun. Only their sideways motion or angular momentum keeps them from falling straight into the solar inferno.

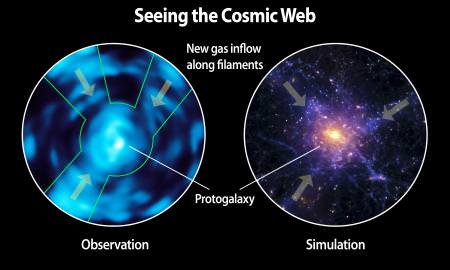

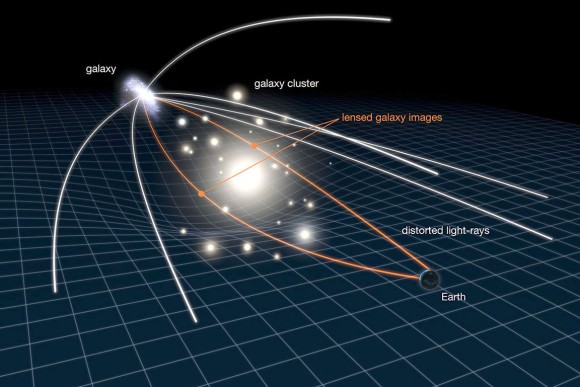

Curved space created by massive objects also bends light rays. Einstein predicted that light from a star passing near the Sun or other massive object would follow this invisible curved spacescape and be deflected from an otherwise straight path. In effect, the object acts as a lens, bending and refocusing the light from the distant source into either a brighter image or multiple and distorted images. Also known as the deflection of starlight, nowadays we call it gravitational lensing.

Simulation of distorted spacetime around a massive galaxy cluster over time

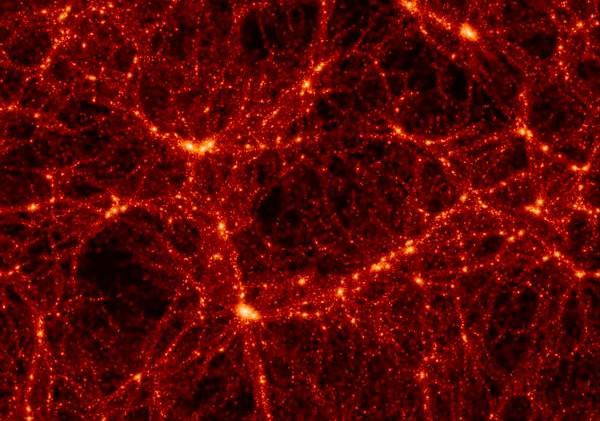

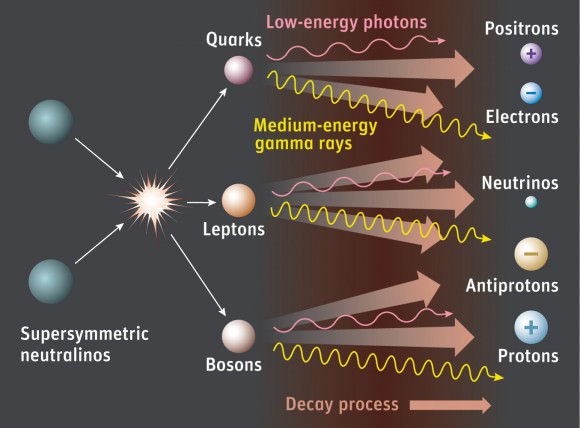

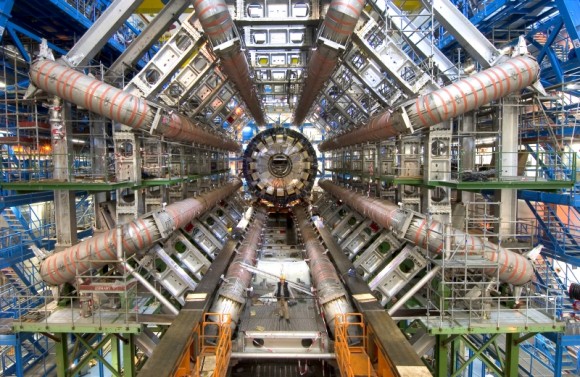

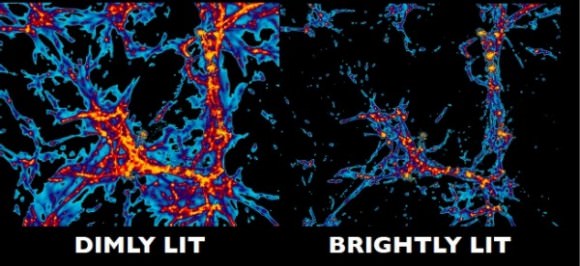

Turns out there are lots of these gravitational lenses out there in the form of massive clusters of galaxies. They contain regular matter as well as vast quantities of the still-mysterious dark matter that makes up 96% of the material stuff in the universe. Rich galaxy clusters act like telescopes – their enormous mass and powerful gravity magnify and intensify the light of galaxies billions of light years beyond, making visible what would otherwise never be seen.

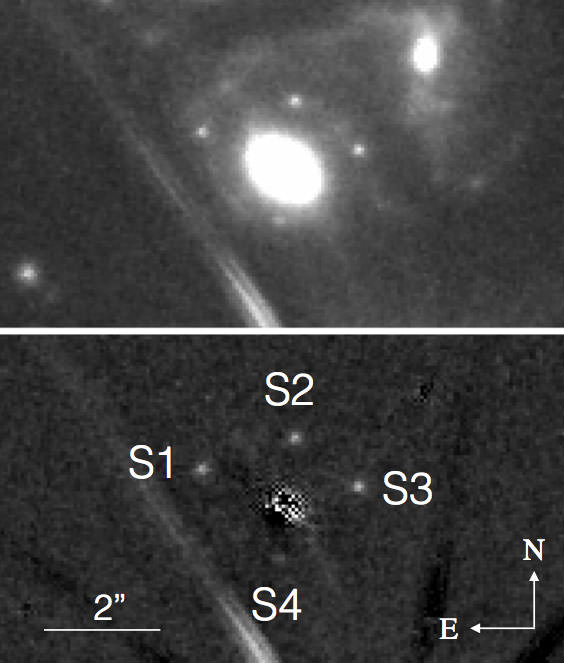

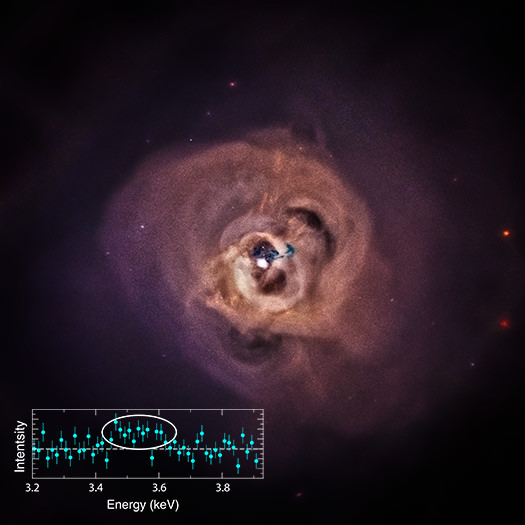

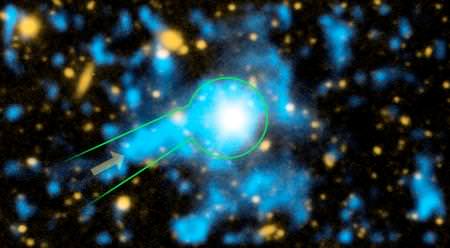

Let’s return to SN Refsdal, named for Sjur Refsdal, a Norwegian astrophysicist who did early work in the field of gravitational lensing. A massive elliptical galaxy in the MACS J1149 cluster “lenses” the 9.4 billion light year distant supernova and its host spiral galaxy from background obscurity into the limelight. The elliptical’s powerful gravity’s having done a fine job of distorting spacetime to bring the supernova into view also distorts the shape of the host galaxy and splits the supernova into four separate, similarly bright images. To create such neat symmetry, SN Refsdal must be precisely aligned behind the galaxy’s center.

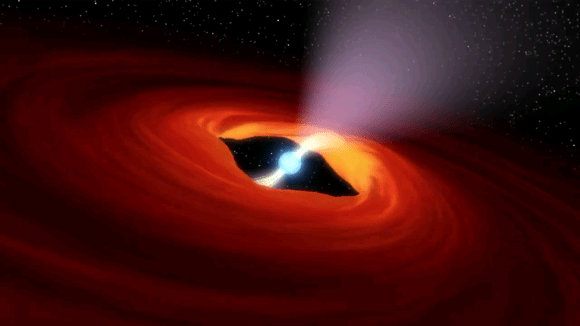

The scenario here bears a striking resemblance to Einstein’s Cross, a gravitationally lensed quasar, where the light of a remote quasar has been broken into four images arranged about the foreground lensing galaxy. The quasar images flicker or change in brightness over time as they’re microlensed by the passage of individual stars within the galaxy. Each star acts as a smaller lens within the main lens.

Detailed color images taken by the GLASS and Hubble Frontier Fields groups show the supernova’s host galaxy is also multiply-imaged by the galaxy cluster’s gravity. According to their recent paper, Kelly and team are still working to obtain spectra of the supernova to determine if it resulted from the uncontrolled burning and explosion of a white dwarf star (Type Ia) or the cataclysmic collapse and rebound of a supergiant star that ran out of fuel (Type II).

The time light takes to travel to the Earth from each of the lensed images is different because each follows a slightly different path around the center of the lensing galaxy. Some paths are shorter, some longer. By timing the brightness variations between the individual images the team hopes to provide constraints not only on the distribution of bright matter vs. dark matter in the lensing galaxy and in the cluster but use that information to determine the expansion rate of the universe.

You can squeeze a lot from a cosmic mirage!