The Distant Gamma-Ray Burst GRB 050904. Image credit: ESO Click to enlarge

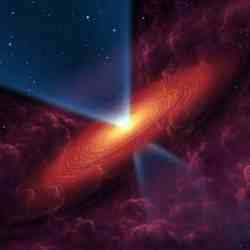

An Italian team of astronomers has observed the afterglow of a Gamma-Ray Burst that is the farthest known ever. With a measured redshift of 6.3, the light from this very remote astronomical source has taken 12,700 million years to reach us. It is thus seen when the Universe was less than 900 million years old, or less than 7 percent its present age.

“This also means that it is among the intrinsically brightest Gamma-Ray Burst ever observed”, said Guido Chincarini from INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera and University of Milano-Bicocca (Italy) and leader of a team that studied the object with ESO’s Very Large Telescope. “Its luminosity is such that within a few minutes it must have released 300 times more energy than the Sun will release during its entire life of 10,000 million years.”

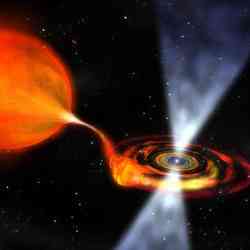

Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are short flashes of energetic gamma-rays lasting from less than a second to several minutes. They release a tremendous quantity of energy in this short time making them the most powerful events since the Big Bang. It is now widely accepted that the majority of the gamma-ray bursts signal the explosion of very massive, highly evolved stars that collapse into black holes.

This discovery not only sets a new astronomical record, it is also fundamental to the understanding of the very young Universe. Being such powerful emitters, these Gamma Ray Bursts serve as useful beacons, enabling the study of the physical conditions that prevailed in the early Universe. Indeed, since GRBs are so luminous, they have the potential to outshine the most distant known galaxies and may thus probe the Universe at higher redshifts than currently known. And because Gamma-ray Burst are thought to be associated with the catastrophic death of very massive stars that collapse into black holes, the existence of such objects so early in the life of the Universe provide astronomers with important information to better understand its evolution.

The Gamma-Ray Burst GRB050904 was first detected on September 4, 2005, by the NASA/ASI/PPARC Swift satellite, which is dedicated to the discovery of these powerful explosions.

Immediately after this detection, astronomers in observatories worldwide tried to identify the source by searching for the afterglow in the visible and/or near-infrared, and study it.

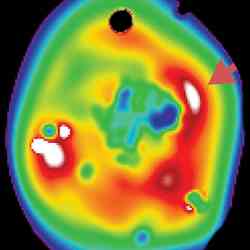

First observations by American astronomers with the Palomar Robotic 60-inch Telescope failed to find the source. This sets a very stringent limit: in the visible, the afterglow should thus be at least a million times fainter than the faintest object that can be seen with the unaided eye (magnitude 21). But observations by another team of American astronomers detected the source in the near-infrared J-band with a magnitude 17.5, i.e. at least 25 times brighter than in the visible.

This was indicative of the fact that the object must either be very far away or hidden beyond a large quantity of obscuring dust. Further observations indicated that the latter explanation did not hold and that the Gamma-Ray Burst must lie at a distance larger than 12,500 million light-years. It would thus be the farthest Gamma-Ray Burst ever detected.

Italian astronomers forming the MISTICI collaboration then used Antu, one of four 8.2-m telescopes that comprise ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) to observe the object in the near-infrared with ISAAC and in the visible with FORS2. Observations were done between 24.7 and 26 hours after the burst.

Indeed, the afterglow was detected in all five bands in which they observed (the visible I- and z-bands, and the near-infrared J, H, and K-bands). By comparing the brightness of the source in the various bands, the astronomers could deduce its redshift and, hence, its distance. “The value we derived has since then been confirmed by spectroscopic observations made by another team using the Subaru telescope”, said Angelo Antonelli (Roma Observatory), another member of the team.

Original Source: ESO News Release