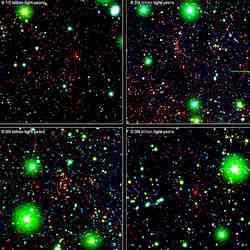

Inward migration of a group of protoplanets, where they’re represented by white circles. Image credit: QMUL Click to enlarge

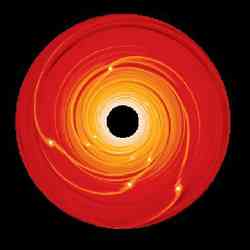

Astronomers think they’ve got a handle on many aspects of planetary formation. But two British researchers have discovered a problem with the formation of gas giant planets. Under their model, the cores of these massive planets should be drawn inward by their parent star in only 100,000 years – not nearly enough time to form into a stable orbit. It could be that the first generations of planets never get past the “clump” stage before they’re destroyed. It’s only the later generations that actually survive long enough to become planets.

Two British astronomers, Paul Cresswell and Richard Nelson present new numerical simulations in the framework of the challenging studies of planetary system formation. They find that, in the early stages of planetary formation, giant protoplanets migrate inward in lockstep into the central star. Their results will soon be published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

In an article to be published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, two British astronomers present new numerical simulations of how planetary systems form. They find that, in the early stages of planetary formation, giant protoplanets migrate inward in lockstep into the central star.

The current picture of how planetary systems form is as follows: i) dust grains coagulate to form planetesimals of up to 1 km in diameter; ii) the runaway growth of planetesimals leads to the formation of ~100 ? 1000 km-sized planetary embryos; iii) these embryos grow in an “oligarchic” manner, where a few large bodies dominate the formation process, and accrete the surrounding and much smaller planetesimals. These “oligarchs” form terrestrial planets near the central star and planetary cores of ten terrestrial masses in the giant planet region beyond 3 astronomical units (AU).

However, these theories fail to describe the formation of gas giant planets in a satisfactory way. Gravitational interaction between the gaseous protoplanetary disc and the massive planetary cores causes them to move rapidly inward over about 100,000 years in what we call the “migration” of the planet in the disc. The prediction of this rapid inward migration of giant protoplanets is a major problem, since this timescale is much shorter than the time needed for gas to accrete onto the forming giant planet. Theories predict that the giant protoplanets will merge into the central star before planets have time to form. This makes it very difficult to understand how they can form at all.

For the first time, Paul Cresswell and Richard Nelson examined what happens to a cluster of forming planets embedded in a gaseous protoplanetary disc. Previous numerical models have included only one or two planets in a disc. But our own solar system, and over 10% of the known extrasolar planetary systems, are multiple-planet systems. The number of such systems is expected to increase as observational techniques of extrasolar systems improve. Cresswell and Nelson’s work is the first time numerical simulations have included such a large number of protoplanets, thus taking into account the gravitational interaction between the protoplanets and the disc, and among the protoplanets themselves.

The primary motivation for their work is to examine the orbits of protoplanets and whether some planets could survive in the disc for extended periods of time. Their simulations show that, in very few cases (about 2%), a lone protoplanet is ejected far from the central star, thus lengthening its lifetime. But in most cases (98%), many of the protoplanets are trapped into a series of orbital resonances and migrate inward in lockstep, sometimes even merging with the central star.

Cresswell and Nelson thus claim that gravitational interactions within a swarm of protoplanets embedded in a disc cannot stop the inward migration of the protoplanets. The “problem” of migration remains and requires more investigation, although the astronomers propose several possible solutions. One may be that several generations of planets form and that only the ones that form as the disc dissipates survive the formation process. This may make it harder to form gas giants, as the disc is depleted of the material from which gas giant planets form. (Gas giant formation may still be possible though, if enough gas lies outside the planets’ orbits, since new material may sweep inward to be accreted by the forming planet). Another solution might be related to the physical properties of the protoplanetary disc. In their simulations, the astronomers assumed that the protoplanetary disc is smooth and non-turbulent, but of course this might not be the case. Large parts of the disc could be more turbulent (as a consequence of instabilities caused by magnetic fields), which may prevent inward migration over long time periods.

This work joins other studies of planetary system formation that are currently being done by a European network of scientists. Our view of how planets form has drastically changed in the last few years as the number of newly discovered planetary systems has increased. Understanding the formation of giant planets is currently one of the major challenges for astronomers.

Original Source: Astronomy & Astrophysics