[/caption]

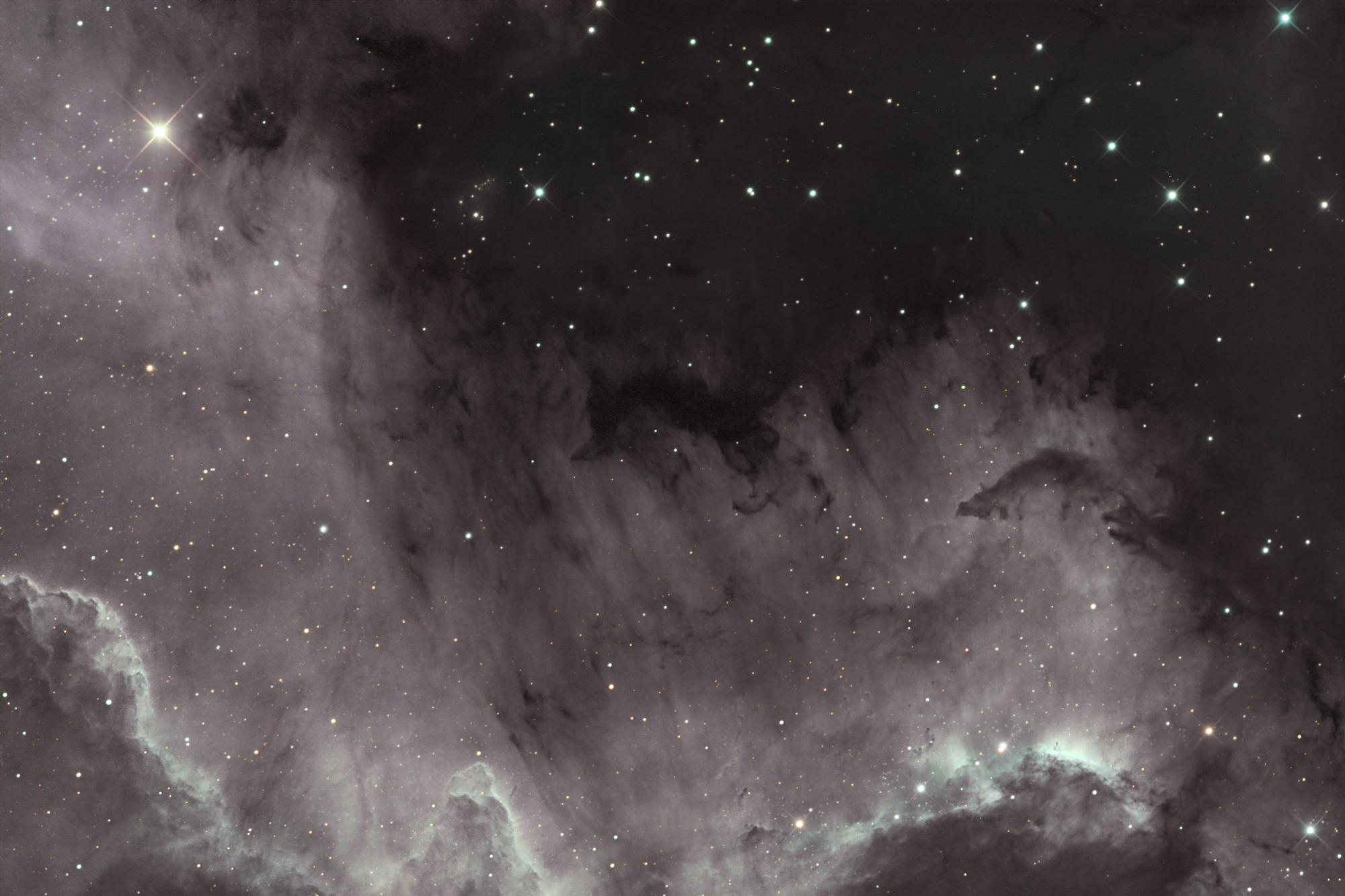

Known as Caldwell 20 to some, NGC 7000 to others and the North America Nebula to most, this diffuse emission/reflection nebula near Deneb can frequently be seen by the unaided eye from a dark location, but the sheer size of this 1600 light year distant gas cloud often confuses people as to the reality of what they are seeing. Let’s take a look at just a few of the bricks in the “Wall”..

Hey you, out there beyond the wall… Is there anybody out there?

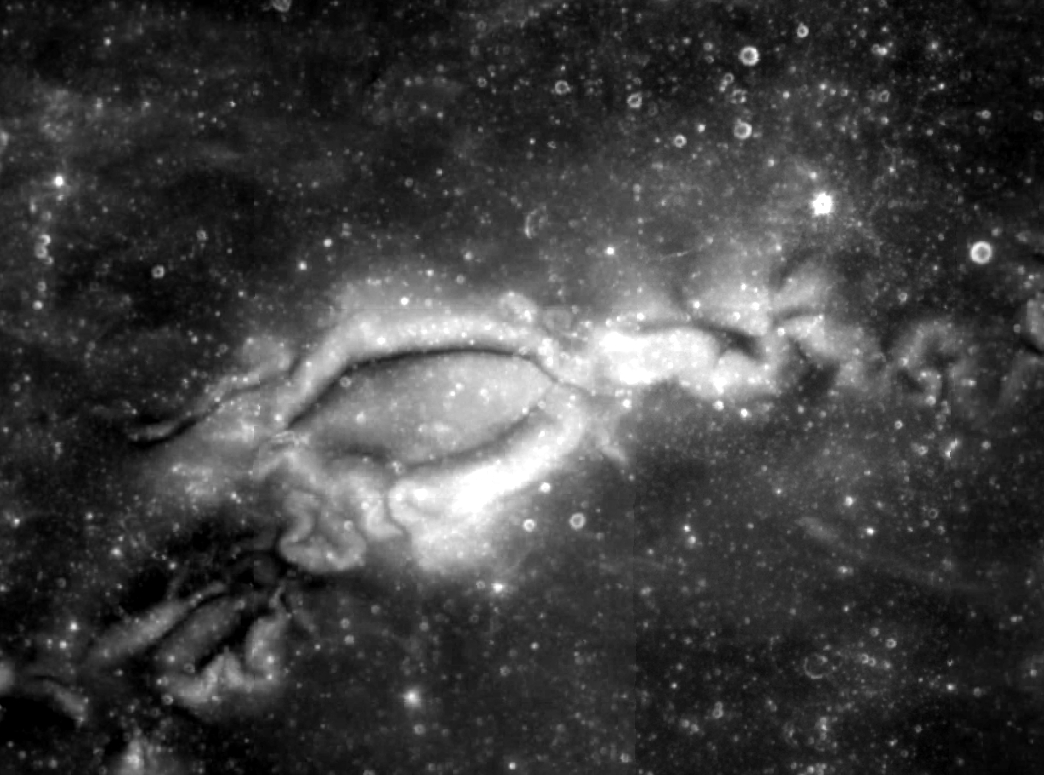

In this image taken by Kent Wood, we are looking a just a close-up of the region shaped like the Gulf of Mexico and often referred to as the “Cygnus Wall”. It is here that light from young, energetic stars is taking the surrounding cold gas fields and warming them, causing an ionization front to form – filled with dense and delightfully delicate filaments. This highly energized “shock front” stands out in bold relief against the complex dark gases and streaking dark dustlanes.

What shall we use… To fill the empty spaces? What shall we use… To complete the wall?

Let’s try star formation, eruptive variables, flare stars and T-Tauri types. According to G.W. Marcy: “A slitless spectrographic search for H..cap alpha.. emission stars in NGC 7000 has revealed 18 new examples, most of which are presumably T Tau stars. An examination of all known T Tau stars in these fields has uncovered no events of the FU Ori type, except for that of V1057 Cygni.” All of these make themselves at home in the warm ionized gas in the local interstellar medium. However, it is the properties of this ionized gas that are so curious to study. In this case, in the faint optical emission lines of hydrogen alpha.

Hey you, don’t help them to bury the light…

Along the bright rim of the wall is where the action is at. According to the work of Koji (et al), it is here where most of the star forming action is going on. “We have found small clusters of near-infrared sources having young stellar object (YSO) colors in some of these objects; most of the cluster members are considered to be older than the IRAS point sources and to be pre–main-sequence stars such as T Tauri stars. In at least six bright-rimmed clouds, the clusters are elongated toward the bright-rim tip or the exciting star(s) of the bright rim with the IRAS sources situated near the other end. There is a tendency for bluer (i.e., older) stars to be located closer to the exciting star(s) and for redder (i.e., younger) stars to be closer to the IRAS sources. This asymmetric distribution of the cluster members strongly suggests small-scale sequential star formation or propagation of star formation from the side of the exciting star(s) to the IRAS position in a few times 105 yr, as a result of the advance of the shock caused by the UV radiation from the exciting star(s).”

And all in all it was just a brick in the wall…

But some of the true beauty is the dust and soot laced clouds filled with PAHs. We learned about those Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, not long ago and just what they mean. And, we know the Cygnus X region is one of the richest star formation sites in the Galaxy. But what about this structure? This Wall?

A distant ship, smoke on the horizon…. You are only coming through in waves.

Believe it or not, NGC 7000 was imaged from the lunar surface during the 1972 Apollo 16 mission and continues to be studied for its polarization properties and scattering in h-alpha wavelengths. It has even had its electron temperature taken to prove that interstellar dust is masking the light we see. However, what we do see may be an illusion. From the studies of R.J. Reynolds; “According to photoionization models of the warm ionized medium, these [O i]/Ha ratios suggest that most of the Ha originates from density-bounded, nearly fully ionized regions along the lines of sight rather than from partially ionized H i clouds or layers of H ii on the surfaces of H i clouds.”

Hey you, out there beyond the wall… Is there anybody out there?

Venture into the dark cloud and find out. According to Laugalys (et al) “Magnitudes and color indices of 430 stars down to V Ëœ 17.5 mag in the eight-color Vilnius + I photometric system were obtained in four areas of diameter 20′ within the dark cloud L935 separating the North America and Pelican nebulae. Spectral types, interstellar color excesses, extinctions and distances of stars were determined from the photometric data. The plot of extinction vs. distance shows that the dark cloud begins at a distance of 520±50 pc. About 40 stars in the cloud, mostly K and M dwarfs, are suspected to have Hα emission; these stars also exhibit infrared excesses. Four of them are known pre-main-sequence stars. Our star set contains J205551.3+435225 (V = 13.24) which, according to Camerón and Pasquali (2005), is the O5 V type star ionizing the North America and Pelican nebulae. If this spectral type is confirmed, the star would have an extinction AV between 9 and 10 magnitudes (depending on the accepted extinction law) and a distance which is not very different from the dust cloud distance.”.

How shall I fill the final places? How should I complete the wall?

I guess the last words would be the illuminating source. In a study done by Comerón and Pasquali; “We present the results of a search for the ionizing star of the North America (NGC 7000) and the Pelican (IC 5070) nebulae complex. The application of adequate selection criteria to the 2MASS JH KS broad-band photometry allows us to narrow the search down to 19 preliminary candidates in a circle of 0o 5 radius containing most of the L935 dark cloud that separates both nebulae. Follow-up near-infrared spectroscopy shows that most of these objects are carbon stars and mid-to-late-type giants, including some AGB stars. Two of the three remaining objects turn out to be later than spectral type B and thus cannot account for the ionization of the nebula, but a third object, 2MASS J205551.25+435224.6, has infrared properties consistent with it being a mid O-type star at the distance of the nebulae complex and reddened by AV ≃ 9.6. We confirm its O5V spectral type by means of visible spectroscopy in the blue. This star has the spectral type required by the ionization conditions of the nebulae and photometric properties consistent with the most recent estimates of their distance. Moreover, it lies close to the geometric center of the complex that other studies have proposed as the most likely location for the ionizing star, and is also very close to the position inferred from the morphology of cloud rims detected in radio continuum. Given the fulfillment of all the conditions and the existence of only one star in the whole search area that satisfies them, we thus propose 2MASS J205551.25+435224.6 as the ionizing star of the North America/Pelican complex.”

All in all… It’s just another brick in the wall.

We would like to thank AORAIA member, Kent Wood for the splendid image and the great research challenge!