Positioned north of the ecliptic plane, the constellation of Perseus was one of the original 48 constellations listed by Ptolemy, and endures as one of the 88 modern constellations.adopted by the IAU. It covers 615 square degrees of sky and ranks 24th in constellation size. Perseus contains between 6 and 22 stars in its primary asterism and houses 65 Bayer Flamsteed designated stars within its confines. It is bordered by the constellations of Cassiopeia, Andromeda, Triangulum, Aries, Taurus, Auriga and Camelopardalis. Perseus is visible to all observers located at latitudes between +90° and ?35° and is best seen at culmination during the month of December.

There is one annual meteor shower associated with Perseus and it is one of the most reliable of all – the Perseids. The peak date occurs on or about August 10th of each year and the radiant – or point or origin is near the Double Cluster. The meteoroid stream duration for this meteor shower lasts about five days, with activity beginning one to two days prior to the peak date and ending two or three days afterwards. The Perseid meteor shower has a wonderful and somewhat grisly history. Often referred to as the “Tears of St. Lawrence” this annual shower coincidentally occurs roughly about the same date as the saint’s death is commemorated on August 10. While scientifically we know the appearance of the shooting stars are the by-products of comet Swift-Tuttle, our somewhat more superstitious ancestors viewed them as the tears of a martyred man who was burned for his beliefs. Who couldn’t appreciate a fellow who had the candor to quip “I am already roasted on one side and, if thou wouldst have me well-cooked, it is time to turn me on the other.” while being roasted alive? If nothing else but save for that very quote, I’ll tip a wave to St. Lawrence at the sight of a Perseid! While the fall rate – the number of meteors seen per hour – of the Perseids has declined in recent years since Swift-Tuttle’s 1992 return, the time to begin your Perseid watch is before the peak date of August 12. If you are contending with a Moon which will interfere with fainter meteors, the later you can wait to observe, the better. The general direction to face will be east around midnight and the activity will move overhead as the night continues. While waiting for midnight or later to begin isn’t a pleasant prospect, by then the Moon has gone far west and we are looking more nearly face-on into the direction of the Earth’s motion as it orbits the Sun, and the radiant – the constellation of the meteor shower origin – is also showing well. For those of you who prefer not to stay up late? Try getting up early instead! How many can you expect to see? A very average and cautiously stated fall rate for this year’s Perseids would be about 30 meteors per hour, but remember – this is a collective estimate. It doesn’t mean that you’ll see one every two minutes, but rather you may see four or five in quick succession with a long period of inactivity in between. You can make your observing sessions far more pleasant by planning for inactive times in advance. Bring a radio along, a thermos of your favorite beverage, and a comfortable place to observe from. The further you can get away from city lights, the better your chances will be.

The long “Y” shape of Perseus has a long and colorful mythological history. Perseus was conceived in a golden rain and he and his mother were cast into the sea in a chest – left to die. His mother prayed to Zeus for deliverance and they were rescued by a fisherman who raised Perseus as his son. Eventually the king, in trying to rid himself of Perseus, demanded horses as a wedding present. Knowing Perseus had none, he chose the head if Medusa instead. With the aid of the gods, Perseus defeated Medusa – and from her body sprang Pegasus, the winged horse. As the story goes, he then to flight to the lands of king Cepheus, where he then continued his saga with Cassiopeia and Andromeda – rescuing the maiden from the Cetus, the sea monster. This is why, according to legend, you find all of these constellations so close together in the sky… and Perseus is depicted holding the head of Medusa, whose most famous star – Algol – represents the eye of the demon.

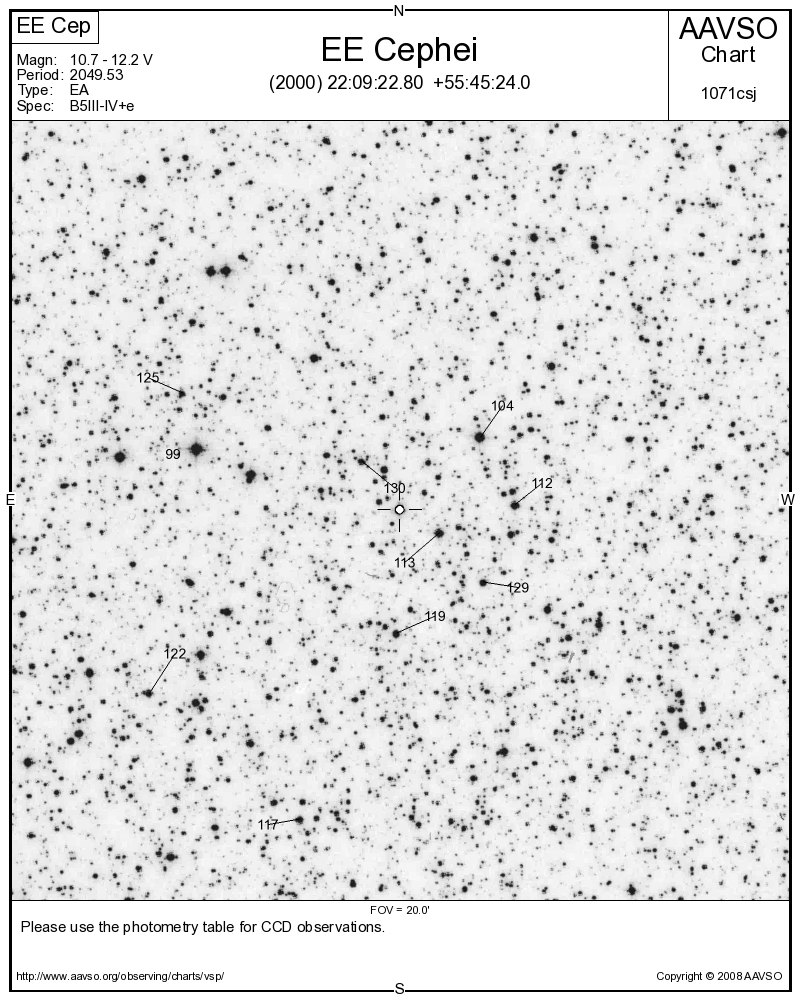

Let’s begin our binocular tour with a look a the “Demon Star” – Beta Persei – the “B” symbol on our map. Beta Persei (RA 03 08 10 Dec +40 57 20) and it is the most famous of all eclipsing variable stars. Ancient history has given this star many names. Associated with the mythological figure Perseus, Beta was considered to be the head of Medusa the Gorgon, and was known to the Hebrews as Rosh ha Satan or “Satan’s Head.” Seventeenth century maps labeled Beta as Caput Larvae, or the “Specter’s Head,” but it is from the Arabic culture that the star was formally named. They knew it as Al Ra’s al Ghul, or the “Demon’s Head,” and we now know it as Algol. Because these medieval astronomers and astrologers associated Algol with danger and misfortune, we are led to believe that Beta’s strange visual variable properties had been noted throughout history. Italian astronomer Geminiano Montanari was the first to record that Algol occasionally “faded,” and its regular timing was cataloged in 1782 by John Goodricke, who surmised that it was being partially eclipsed by a dark companion orbiting it. Thus was born the theory of the eclipsing binary, which was proved spectroscopically for Algol in 1889 by H. C. Vogel. Located 93 light-years away from Earth, Algol is the nearest eclipsing binary, and is treasured by the amateur astronomer because it requires no special equipment to easily follow its stages. Normally Beta Persei holds a magnitude of 2.1, but approximately every three days it dims to magnitude 3.4 and gradually brightens again. The entire eclipse only lasts about 10 hours! Although Algol is known to have two additional spectroscopic companions, the true beauty of watching this variable star is not telescopic – but visual.

Now, let’s use our binoculars and head for Alpha Persei – the “a” symbol on our map. The brightest star of this constellation is also called Mirfak . It is a supergiant star of stellar spectral type F5 Ib with an apparent brightness of 1.79 magnitude and resides at a distance of about 590 light-years. Is it big? You bet. Mirfak is about 62 times larger than our Sun and shines 5000 times brighter, but the beauty is in the field. If you’ve noticed that Alpha is in a group of stars, you’ve noticed right. It’s called the Alpha Persei Association. Viewable with the unaided eye, but best in binoculars, this young, moving star cluster is also known as Melotte 20 or Collinder 39 and is around 601 light years away. Brightest members include Alpha, Delta, Epsilon, Psi, 29, 30, 34 and 48 Persei.

Keep your binoculars handy as we head off to NGC 869 and NGC 884 – the “Double Cluster”. These two open stars clusters (NGC 869 (RA 02:19.1 Dec +57:09) and NGC 884 (RA 02:22:0 Dec +57:08) are perhaps the most beautiful objects of the night sky for binoculars and small, rich field telescopes. Both lie at distances of more than 7,000 light years and are separated by several hundred light-years. Often seen by the unaided eye as a hazy patch in the winter Milky Way, the clusters were first recorded by Hipparchus, but have likely been known since antiquity. NGC 869 is considered to be as much as 19 million years old and this OB1 association sometimes is called Chi Persei. Its companion, NGC 884 is nearer to 12 million years old and is dominated by bright blue stars which notes its youth. Also look for a smattering of orange stars in larger telescopes!

Ready to get Messier? Then locate Messier 34 (RA 02:42:1 Dec +42:46). In binoculars, M34 will show around a dozen fainter stars clustered together, and perhaps a dozen more scattered around the field. Small telescopes at low power will appreciate M34 for its resolvability and the distinctive orange star in the center. Larger aperture scopes will need to stay at lowest power to appreciate the 18 light-year span of this 100 million year old cluster, but take the time to power up and study. You will find many challenging doubles inside!

Now hop on to NGC 1342 (RA 3:31.6 Dec +37:20). Holding a respectable magnitude 7 and covering about 14 arc minutes of sky, this small, compressed, open cluster of stars is well within binocular and small telescope range. It’s been studied for galactic disc metallicity and is on many binocular and deep sky observing lists.

How about two more galactic star clusters? Then try your hand at NGC 1545 (RA 4:20:9 Dec +50:15). It’s around 6th magnitude, but at 18 arc minutes in size will require at least a small telescope to separate it from the starry background. It has been studied for universality of initial mass function of open star clusters. More northern NGC 1528 (RA 4:15:4 Dec +51:14) is about the same magnitude, but a little larger and is also known as Herschel 61, Collinder 47 and Melotte 23.

What about NGC 1499? NGC 1499 (RA 04:00:07 Dec +36:37) is the “California Nebula”. If you’re able to view under very dark skies, the California Nebula can be seen unaided and in binoculars, but its low surface brightness makes it tough for a telescope. NGC 1499 is probably illuminated by Xi Persei, a hot blue-white main sequence star of spectral type O7e. This star belongs to an association of young stars which probably arose from this interstellar cloud, the Perseus OB2 association. What a great opportunity for astrophotographers!

You can also try IC 348 (RA 3:44.5 Dec +32:17). This open star cluster with nebulosity has an apparent magnitude of 7 – but that doesn’t mean it’s bright or easy. It’s a very faint reflection nebula that’s going to require perfect conditions and probably the aid of a nebula filter, too. The “Flying Ghost” has been the subject of many studies, including the search for outflows and protostars. In 2006, the Spitzer Space Telescope turned an eye its way to find disc-less T-Tauri type stars as well as thosel as surrounded by thick, primordial disks. Why is that important? “The disk longevity and thus conditions for planet formation appear to be most favorable for the K6-M2 stars, which are objects of comparable mass to the Sun for the age of this cluster.”

There are many other wonderful deep sky objects in Perseus, so get a good star chart and enjoy the “Hero”!

Sources:

Chandra Observatory

Wikipedia

Chart Courtesy of Your Sky.