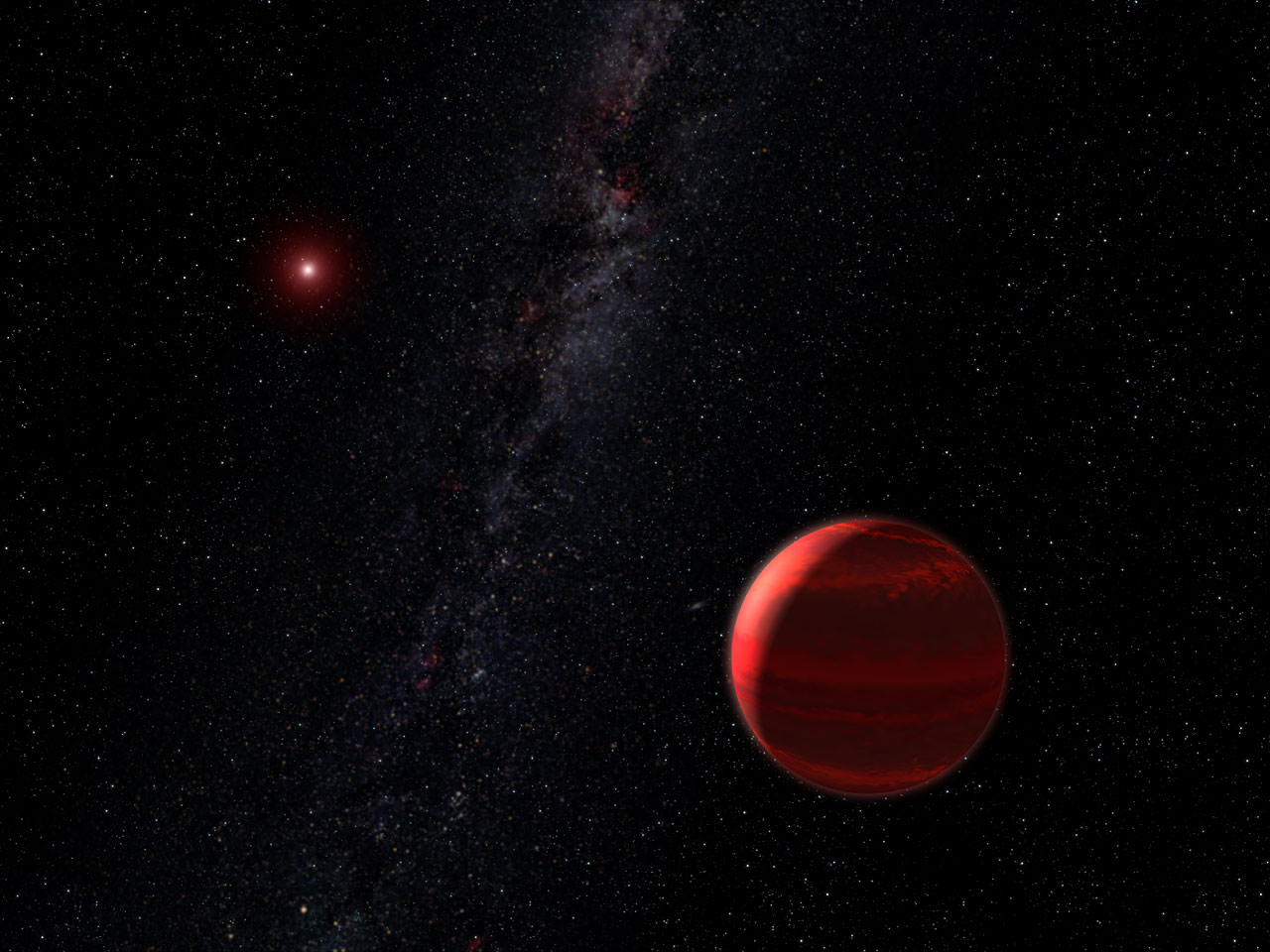

In 2007, something strange happened to a distant star near the centre of our galaxy; it underwent what is known as a ‘microlensing’ event. This transient brightening didn’t have anything to do with the star itself, it had something to do with what passed in front of it. 1,700 light years away between us and the distant star, a brown dwarf crossed our line of sight with the starlight. Although one would think that the star would have been blocked by the brown dwarf, its light was actually amplified, generating a flash. This flash was created via a space-time phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

Although lensing isn’t rare in itself (although this particular event is considered the “most extreme” ever observed), the fact that astronomers had the opportunity to witness a brown dwarf causing it means that either they were very lucky, or we have to think about re-writing the stellar physics textbooks…

“By several measures OGLE-2007-BLG-224 was the most extreme microlensing event (EME) ever observed,” says Andrew Gould of Ohio State University in Columbus in a publication released earlier this month, “having a substantially higher magnification, shorter-duration peak, and faster angular speed across the sky than any previous well-observed event.”

OGLE-2007-BLG-224 revealed the passage of a brown dwarf passing in front of a distant star. The gravity of this small “failed star” deflected the starlight path slightly, creating a gravitational lens very briefly. Fortunately there were a number of astronomers prepared for the event and captured the transient flash of starlight as the brown dwarf focused the light for observers here on Earth.

From these observations, Gould and his team of 65 international collaborators managed to calculate some characteristics of the brown dwarf “lens” itself. The brown dwarf has a mass of 0.056 (+/- 0.004) solar masses, with a distance of 525 (+/- 40) parsecs (~1,700 light years) and a transverse velocity of 113 (+/- 21) km/s.

Although getting the chance to see this happen is a noteworthy in itself, the fact that it was a brown dwarf that acted as the lens is extremely rare; so rare in fact, that Gould believes something is awry.

“In this light, we note that two other sets of investigators have concluded that they must have been ‘lucky’ unless old-population brown-dwarfs are more common than generally assumed,” Gould said.

Either serendipity had a huge role to play, or there are far more brown dwarfs out there than we thought. If there are more brown dwarfs, something isn’t right with our understanding of stellar evolution. Brown dwarfs may be a more common feature in our galaxy than we previously calculated…

Sources: “The Extreme Microlensing Event OGLE-2007-BLG-224: Terrestrial Parallax Observation of a Thick-Disk Brown Dwarf,” Gould et al., 2009. arXiv:0904.0249v1 [astro-ph.GA], New Scientist, Astroengine.com