[/caption]

Some satellites get all the glory. While Hubble, Chandra, and Spitzer frequently make headlines with their stunning images, many other space based observatories silently toil away. One of them, known as the Payload for Antimatter Matter Exploration and Light-nuclei Astrophysics (PAMELA) has been in orbit since 2006, but rarely receives media attention although a stunning discovery has led to the publication of over 300 papers within a single year. A new paper in that onslaught has proposed an interesting new object: pulsars powered by white dwarfs.

PAMELA isn’t a satellite in its own right. It piggybacks on another satellite. Its mission is to observe high energy cosmic rays. Cosmic rays are particles, whether they be protons, electrons, nuclei of entire atoms, or other pieces, that are accelerated to high velocities, often from exotic sources and cosmological distances.

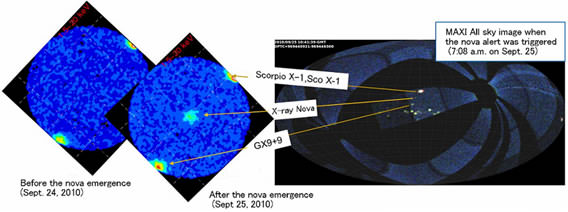

Among the types of particles PAMELA detects is the elusive positron. This anti-particle of the electron is quite rare due to the scarcity of anti-matter in general in our universe. However, much to the surprise of astronomers, in the range of 10 – 100 GeV, PAMELA has reported an abundance of positrons. In even higher ranges (100 GeV – 1 TeV) astronomers have found that there is a rise in both electrons and positrons. The conclusion from this is that something is able to actually create these particles in these energy ranges.

A flurry of papers went to publication to explain this unexpected finding. Explanations ranged from showers of particles created by even higher energy cosmic rays striking the interstellar medium, to the decay of dark matter, to neutron stars, pulsars, supernovae, and gamma ray bursts. Indeed, many events that produce high energies are sufficient to spontaneously produce matter from energy through the process of pair production. However, the range of these ejected particles would be limited. Effects, such as synchrotron and inverse Compton emission would drain their energy over large distances and as such, by the time they reached PAMELA’s detectors would be too low energy to account for the excesses in the observed energy ranges. From this, astronomers are presuming the culprits are in the local universe.

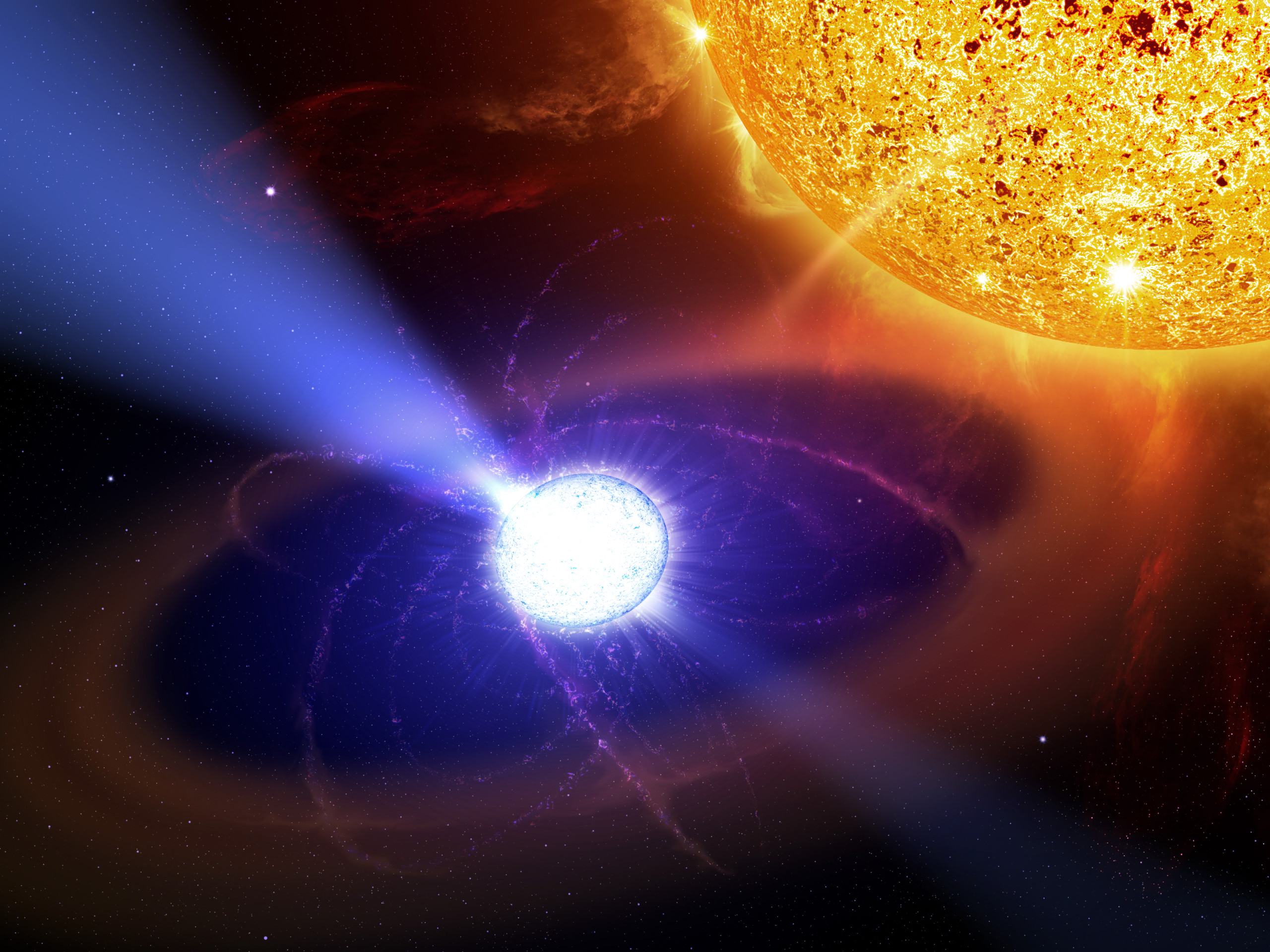

Joining the long list of candidates, a new paper has proposed a mundane object could be responsible for the high energy necessary to create these energetic particles, albeit with an unusual twist. Neutron stars, one of the potential objects formed in a supernova, are known to release large amounts of energies when spinning quickly while creating a strong magnetic field in the form of pulsars, but the authors propose that white dwarfs, the products of the slow death from stars not massive enough to result in a supernova, may be able to do the same thing. The difficulty in creating such a white dwarf pulsar is that, since white dwarfs don’t collapse to such a small size, they don’t “spin up” as much as they conserve angular momentum and shouldn’t have the sufficient angular velocity necessary.

The authors, led by Kazumi Kashiyama at Kyoto University propose that a white dwarf may reach the necessary rotational speed if they undergo a merger or accrete a sufficient amount of mass. This idea is not unheard of since white dwarf mergers and accretion are already implicated in Type Ia Supernovae. The combination of this with the expectation that around 10% of white dwarfs are expected to have magnetic fields of 106 Gauss, the steps necessary to produce a pulsar from a white dwarf seem to be in place. They note that since white dwarfs tend to have weaker magnetic fields, they shed their angular momentum more slowly and would last longer. Although this duration is still far longer than humans can possibly watch, this may indicate that many of the pulsars observed in our own galaxy are white dwarfs.

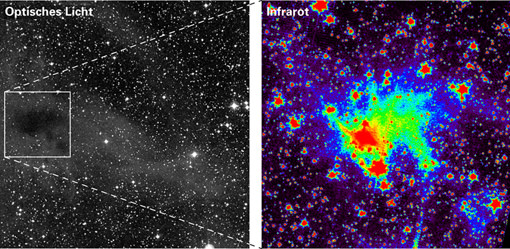

Next, the authors hope to conclusively identify such a star. The creation of each of these types of pulsars may provide a clue: Since neutron stars form from supernovae, they are surrounded by a shell of gas that contains a shock front from the supernova itself, which is more dense than the interstellar medium in general. As particles pass through this shock front, some of them would be lost. The same would not be said for white dwarfs which formed from a more gentle release and aren’t impeded by the relatively high density area. This shift in energy distributions may be one distinguishing characteristic.

Some stars have even been tentatively proposed as candidates for white dwarf pulsars. AE Aquarii was seen to give off some pulsar-like signals. EUVE J0317-855 is another white dwarf that appears to meet the qualifications, although no signals have been detected from this star. This new class of stars would be able to explain the excess signal in the higher energy range detected by PAMELA and will likely be the target of further observational searches in the future.