The Kuiper Belt has been an endless source of discoveries over the course of the past decade. Starting with the dwarf planet Eris, which was first observed by a Palomar Observatory survey led by Mike Brown in 2003, many interesting Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) have been discovered, some of which are comparable in size to Pluto.

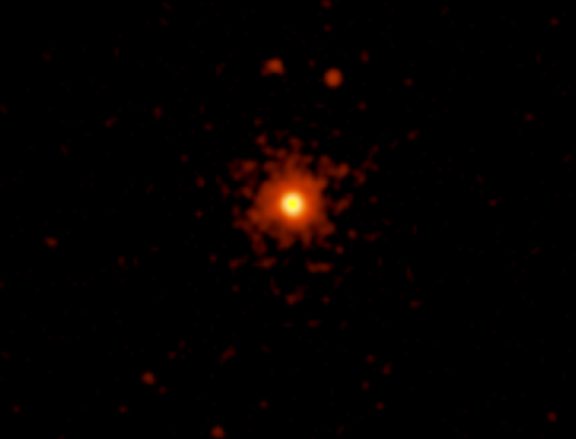

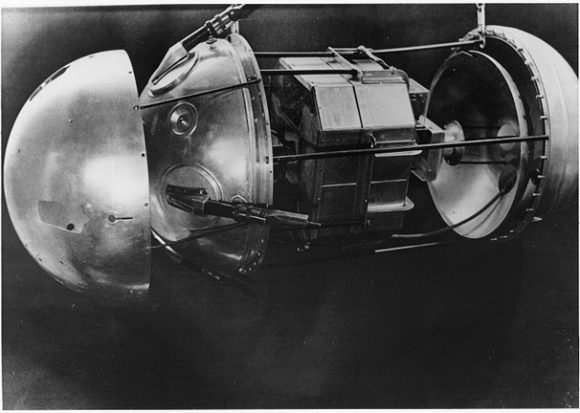

And according to a new report from the IAU Minor Planet Center, yet another body has been discovered beyond the orbit of Pluto. Officially designated as 2014 UZ224, this body is located about 14 billion km (90 AUs, or 8.5 billion miles) from the Sun. This dwarf planet is not only the latest member of the our Solar family, it is also the second-farthest body from our Sun with a stable orbit.

The discovery was made by David Gerdes, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Michigan, and various colleagues associated with at the Dark Energy Survey (DES) – a project which relies on the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. In the past, Gerdes’ research has focused on the detection of dark energy and the expansion of the Universe.

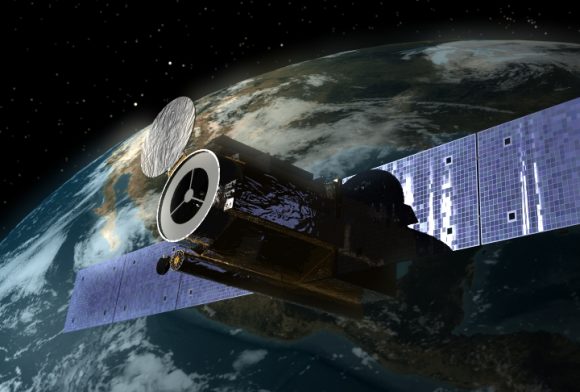

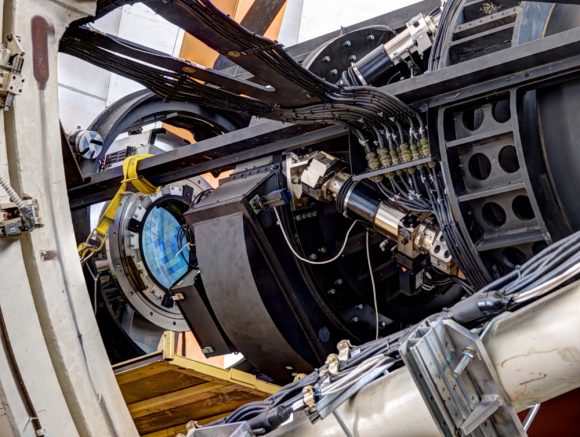

Towards this end, DES has spent the past five years surveying roughly one-eighth of the sky using the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), a 570-Megapixel camera mounted on the Victor M. Blanco telescope at Cerro Tololo. This instrument was commissioned by the US. Dept of Energy to conduct surveys of distant galaxies, and Dr. Gerdes had a hand in creating.

Not surprisingly, this same technology has also allowed for discoveries to be made at the edge of the Solar System. Two years ago, this is precisely what Gerdes challenged a group of undergraduate students to do (as part of a summer project). These students examined images taken by DES between 2013-2016 for indications of moving objects. Since that time, the analysis team has grown to include senior scientists, postdocs, graduate and undergraduate students.

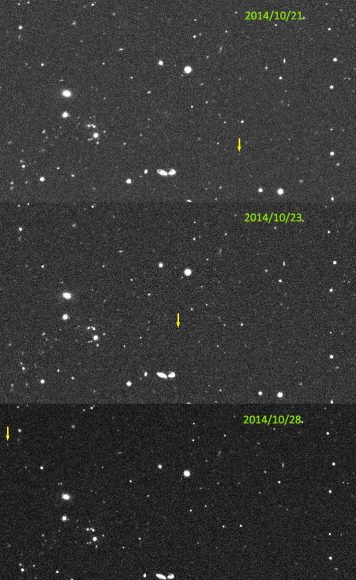

Whereas distant stars and galaxies would appear stationary in these images, distant TNOs showed up in different places over time – hence why are called “transients”. As Dr. Gerdes explains in his 2014 UZ224 Fact Sheet, which is available through his University of Michigan homepage:

“To identify transients, we used a technique known as “difference imaging”. When we take a new image, we subtract from it an image of the same area of the sky taken on a different night. Objects that don’t change disappear in this subtraction, and we’re left with only the transients… This process yields millions of transients, but only about 0.1% of them turn out to be distant minor planets. To find them, we must “connect the dots” and determine which transients are actually the same thing in different positions on different nights. There are many dots and MANY more possible ways to connect them.”

This was a difficult process. In addition to needing thousands of computers at Fermilab to process the hundreds of terabytes of data, the team had to write special programs to do it. Gerdes and his colleagues also relied on help from Professors Masao Sako and Gary Bernstein of the University of Pennsylvania, who contributed the key breakthroughs that allowed them to perform difference imaging over the entire survey area.

In the end, dozens of new Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) were discovered, one of which was 2014 UZ224. According to their observations, its diameter could be anywhere from 350 to 1200 km, and it takes 1,136 years to complete a single orbit of our Sun. For the sake of perspective, Pluto is 2370 km in diameter, and has an orbital period of 248 years.

Stephanie Hamilton, a graduate student at the University of Michigan, was personally involved with the project. Her role was to determine the size of 2014 UZ224, which was difficult from initial observations alone. As she told Universe Today via email:

“The object’s brightness in visible light alone depends both on its size and how reflective it is, so you can’t uniquely determine one of those properties without assuming a value for the other. Fortunately there’s a solution to that problem – the heat the object emits is also proportional to its size, so obtaining a thermal measurement in addition to the optical measurements means we would then be able to calculate the object’s size and albedo (reflectance) without having to assume one or the other.

“We were able to obtain an image of our object at a thermal wavelength using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. I am working on combining all of our data together to determine the size and albedo, and we expect to submit a paper on our results around mid-November or so.”

But as with all things related to “dwarf planets”, there has been some disagreement over this discovery. Given the dimensions of the object, there are some who question whether or not the label applies. But as Gerdes indicates on the Fact Sheet, this body fits most of the prerequisites:

“According to the official IAU guidelines, a dwarf planet must satisfy four criteria. It must a) orbit the sun (check!), b) not be a satellite (check!) c) not have cleared the neighborhood around its orbit (check!) and d) have enough mass to be round. It’s this last item that’s uncertain, and the only way for sure is to get a picture that’s detailed enough to actually see its shape. Nevertheless, an object over 400 km in diameter is likely to be round.”

Gerdes and his team expect to be busy, authoring the paper that will detail their findings, using the ALMA array to get more assessments of 2014 UZ224 size, and sifting through the data to look for more objects in the Kuiper Belt. This includes the fabled Planet 9, which astronomers have been seeking out for years.

Given its distance from the Sun, 2014 UZ224’s orbit would not be influenced by the presence of Planet 9, and is therefore of no help. However, Gerdes is optimistic that the evidence of this massive body is there in the data. Given time, and a lot of data-processing, they just might find it! In the meantime, this newly discovered object is likely to be the focal point of a lot of fascinating research.

“It’s an interesting object in its own right – distant objects like this are ‘cosmic leftovers’ from the primordial disk that gave birth to the solar system,” writes Gerdes. “By studying them and learning more about their distribution, orbital characteristics, sizes, and surface properties, we can learn more about the processes that gave birth to the solar system and ultimately to us.”

Further Reading: 2014 UZ224 Fact Sheet (University of Michigan)