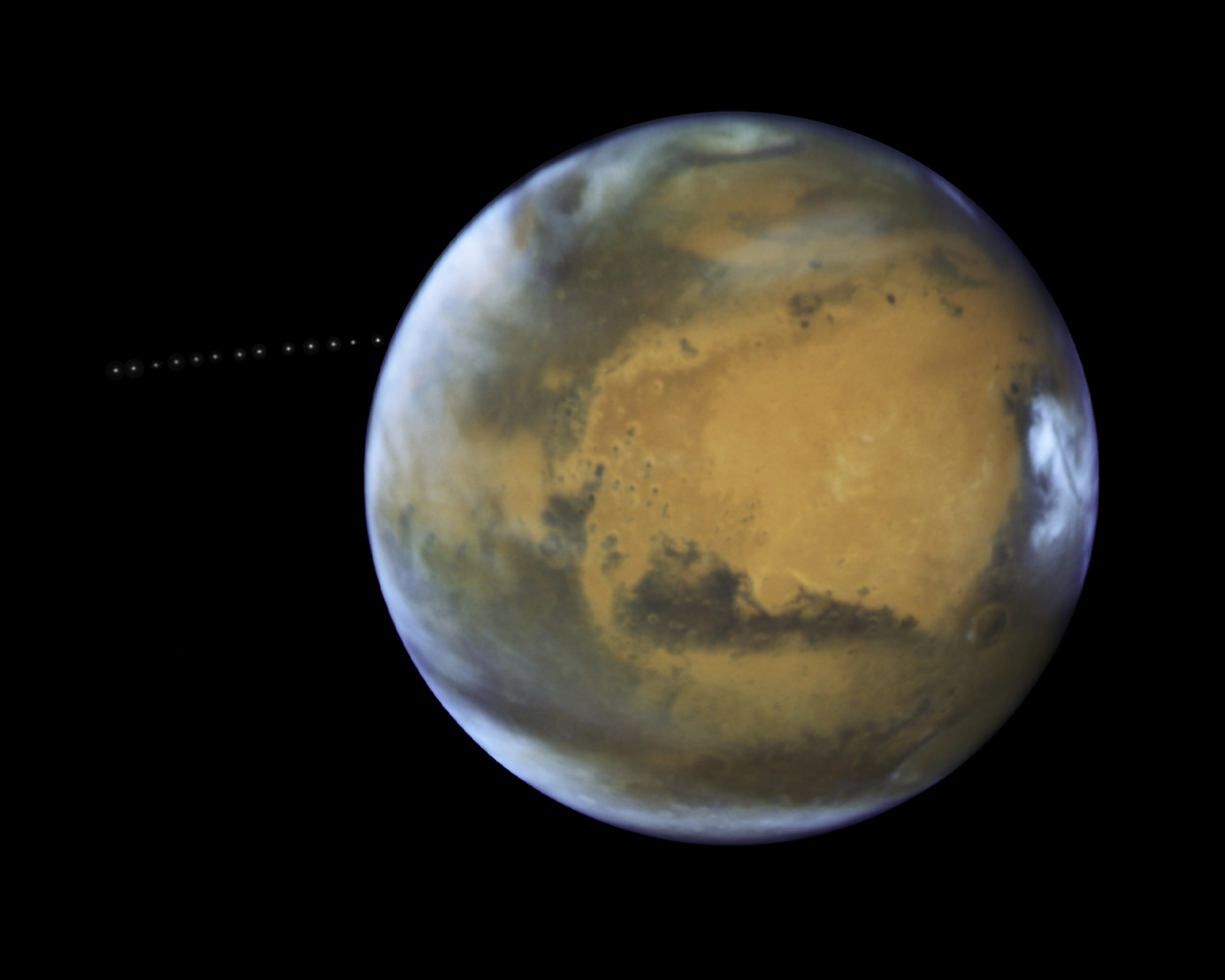

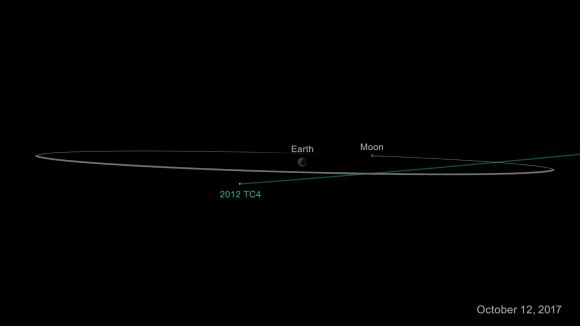

This coming October, an asteroid will fly by Earth. Known as 2012 TC4, this small rock is believed to measure between 10 and 30 meters (30 and 100 feet) in size. As with most asteroids, this one is expected to sail safely past Earth without incident. This will take place on October 12th, when the asteroid will pass us at a closest estimated distance of 6,800 kilometers (4,200 miles) from Earth’s surface.

That’s certainly good news. But beyond the fact that it does not pose a threat to Earth, NASA is also planning on using the occasion to test their new detection and tracking network. As part of their Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO), this network is responsible for detecting and tracking asteroids that periodically pass close to Earth, which are known as Potentially Hazardous Objects (PHOs)

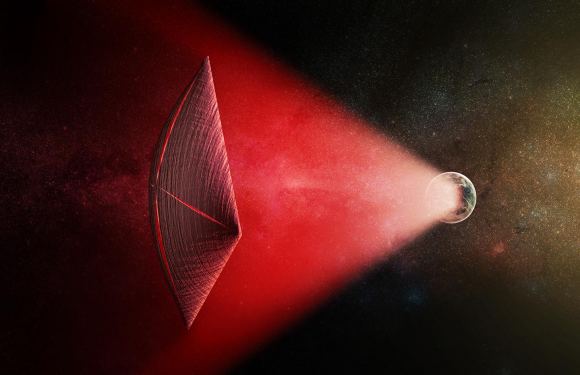

In addition to relying on data provided by NASA’s Near-Earth Object (NEO) Observations Program. the PDCO also coordinates NEO observations conducted by National Science Foundation (NSF)-sponsored ground-based observatories, as well as space situational awareness facilities run by the US Air Force. Aside from finding and tracking PHOs, the PDCO is also responsible for coming up with ways of deflecting and redirecting them.

The PDCO was officially created in response to the NASA Office of Inspector General’s 2014 report, titled “NASA’s Efforts to Identify Near-Earth Objects and Mitigate Hazards.” Citing such events as the Chelyabinsk meteor, and how such events are relatively common, the report indicated that coordination, early warning and mitigation strategies were needed for the future:

“[I]n February 2013 an 18-meter (59 foot) meteor exploded 14.5 miles above the city of Chelyabinsk, Russia, with the force of 30 atomic bombs, blowing out windows, destroying buildings, injuring more than 1,000 people, and raining down fragments along its trajectory… Recent research suggests that Chelyabinsk-type events occur every 30 to 40 years, with a greater likelihood of impact in the ocean than over populated areas, while impacts from objects greater than a mile in diameter are predicted only once every several hundred thousand years.”

The PDCO was established in 2016, which makes this upcoming flyby the first chance they will have to test their network of observatories and scientists dedicated to planetary defense. Michael Kelley is the program scientist and the NASA Headquarters lead for the TC4 observation campaign, which has been monitoring 2012 TC4 for years. As he said in a recent NASA press statement:

“Scientists have always appreciated knowing when an asteroid will make a close approach to and safely pass the Earth because they can make preparations to collect data to characterize and learn as much as possible about it. This time we are adding in another layer of effort, using this asteroid flyby to test the worldwide asteroid detection and tracking network, assessing our capability to work together in response to finding a potential real asteroid threat.”

In addition, the flyby will be an opportunity to reacquire 2012 TC4, which astronomers lost track of in 2012 when it moved beyond the range of their telescopes. For this reason, people like Professor Vishnu Reddy of the University of Arizona are also excited. A member of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, Reddy also leads the campaign to reacquire the asteroid. As he indicated, this flyby will be a chance for collaborative observation.

“This is a team effort that involves more than a dozen observatories, universities and labs across the globe so we can collectively learn the strengths and limitations of our near-Earth object observation capabilities,” he said. “This effort will exercise the entire system, to include the initial and follow-up observations, precise orbit determination, and international communications.”

2012 TC4 was originally discovered on Oct. 5th, 2012, by the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) at the Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii. After it sped past Earth in that same year, it has not been directly observed since. And while it is slightly larger than the meteor that exploded in Earth’s atmosphere near Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013, scientists are certain that it will pass us by at a safe distance.

This is based on tracking data that was collected by scientists from NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS). After monitoring 2012 TC4 for a period of seven days after it was discovered in 2012, they determined that at its closest approach, the asteroid will pass no closer than 6,800 km (4,200 mi) to Earth. However, it is more likely that it will pass us at distance of about 270,000 km (170,000 mi).

This would place it at a distance that is about two-thirds the distance between the Earth and the Moon. The last time this asteroid passed Earth, it did so at a distance that was one-quarter the distance between the Earth and the Moon. Therefore, the odds of it passing by without incident are even greater this time around. So rather than representing a threat, the passage of this asteroid represents a good chance for research.

As Paul Chodas, the manager of the CNEOS at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, stated:

“This is the perfect target for such an exercise because while we know the orbit of 2012 TC4 well enough to be absolutely certain it will not impact Earth, we haven’t established its exact path just yet. It will be incumbent upon the observatories to get a fix on the asteroid as it approaches, and work together to obtain follow-up observations than make more refined asteroid orbit determinations possible.”

By monitoring 2012 TC4 as it flies by, astronomers will be able to refine their knowledge about the asteroid’s orbit, which will help them to predict and calculate future flybys with even greater precision. This will further mitigate the risk posed by PHOs down the road, and help the PDCO to develop and test strategies to address possible future impacts.

In short, remain calm! This flyby is a good thing!

Further Reading: NASA