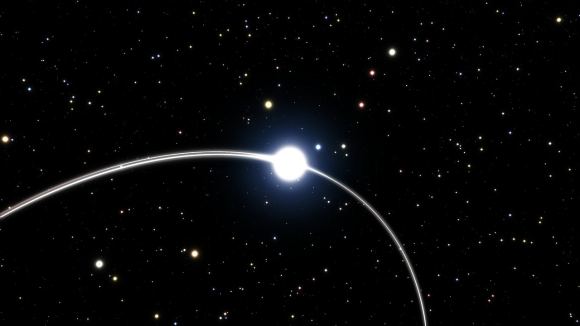

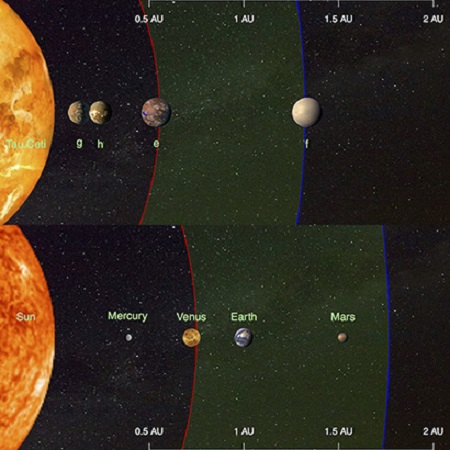

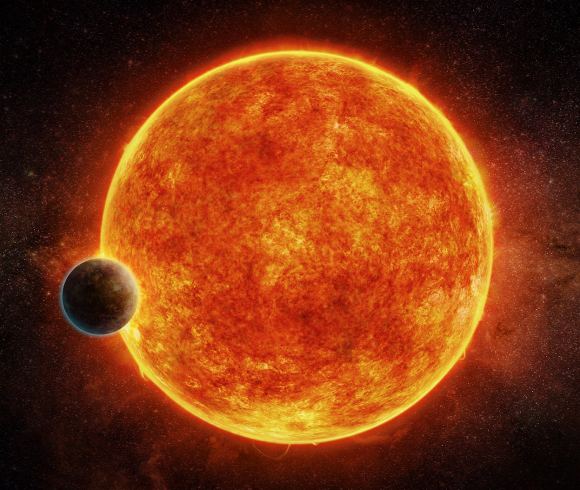

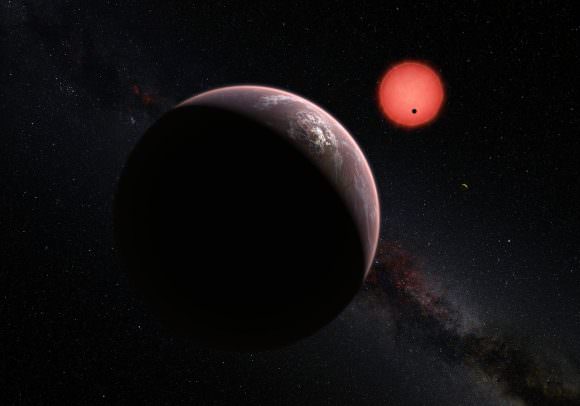

Studies of low-mass, ultra-cool and ultra-dim red dwarf stars have turned up a wealth of extra-solar planets lately. These include the discoveries of a rocky planet orbiting the closest star to the Solar System (Proxima b) and a seven-planet system just 40 light years away (TRAPPIST-1). In the past few years, astronomers have also detected candidates orbiting the stars Gliese 581, Innes Star, Kepler 42, Gliese 832, Gliese 667, Gliese 3293, and others.

The majority of these planets have been terrestrial (i.e. rocky) in nature, and many were found to orbit within their star’s habitable zone (aka. “goldilocks zone”). However the question whether or not these planets are tidally-locked, where one face is constantly facing towards their star has been an ongoing one. And according to a new study from the University of Washington, tidally-locked planets may be more common than previously thought.

The study – which is available online under the title “Tidal Locking of Habitable Exoplanets” – was led by Rory Barnes, an assistant professor of astronomy and astrobiology at the University of Washington. Also a theorist with the Virtual Planetary Laboratory, his research is focused on the formation and evolution of planets that orbit in and around the “habitable zones” of low-mass stars.

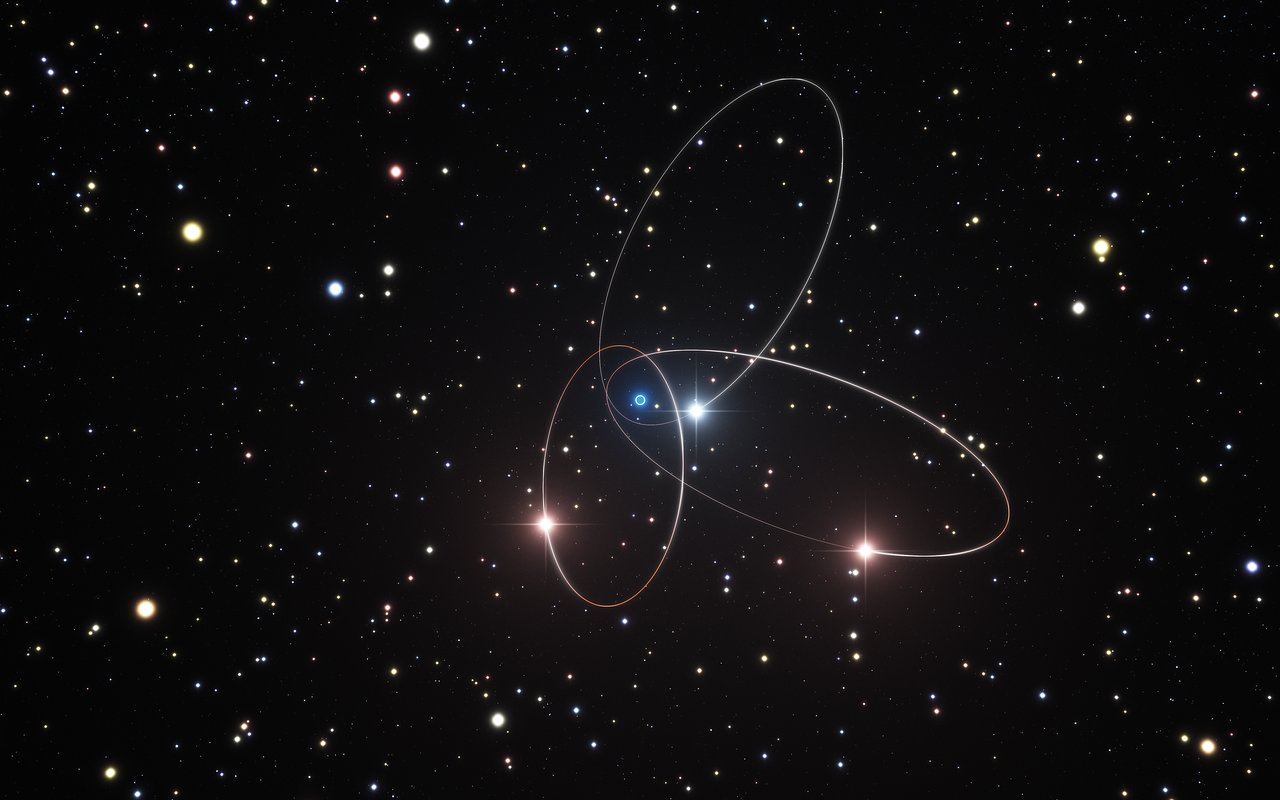

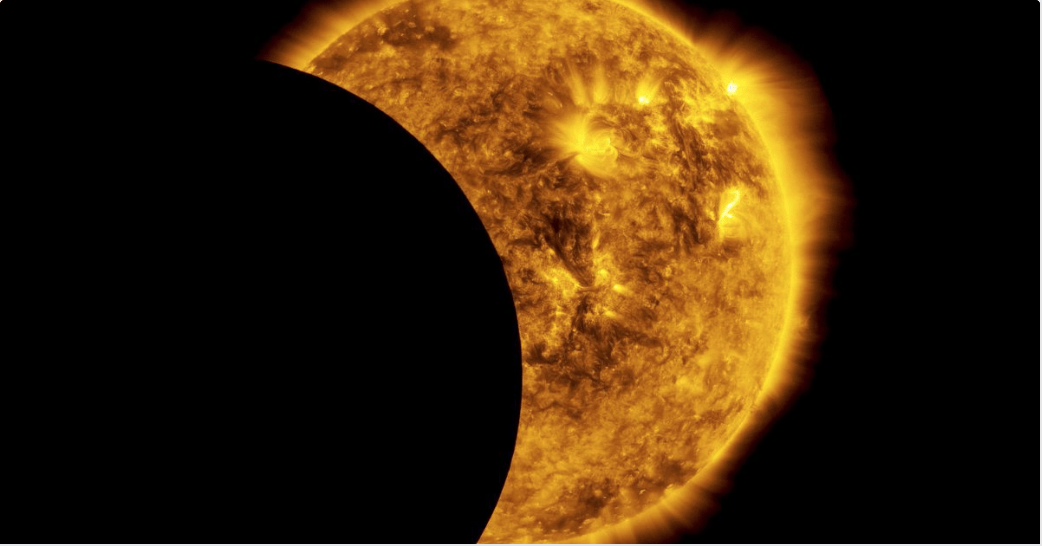

For modern astronomers, tidal-locking is a well-understood phenomena. It occurs as a result of their being no net transfer of angular momentum between an astronomical body and the body it orbits. In other words, the orbiting body’s orbital period matches its rotational period, ensuring that the same side of this body is always facing towards the planet or star it orbits.

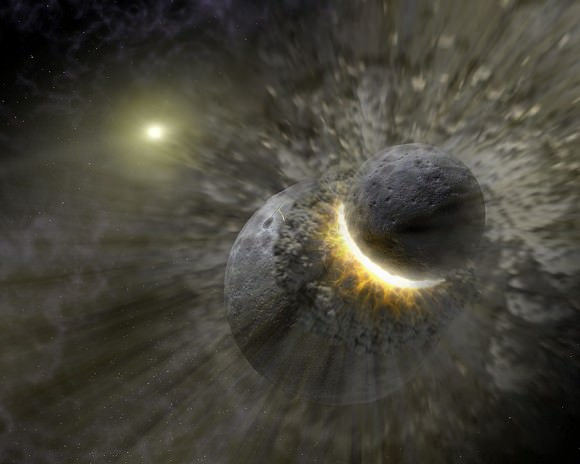

Consider Earth’s only satellite – the Moon. In addition to taking 27.32 days to orbit Earth, the Moon also takes 27.32 days to rotate once on its axis. This is why the Moon always presents the same “face” towards Earth, while the side that faces away is known as the “dark side”. Astronomers believe this became the case after a Mars-sized object (Theia) collided with Earth some 4.5 billion years ago.

Aside from throwing up debris that would eventually form the Moon, the impact is believed to have struck Earth at such an angle that it gave our planet an initial rotation period of 12 hours. In the past, researchers have used this 12-hour estimation of Earth’s rotation as a model for exoplanet behavior. However, prior to Barnes’ study, no systematic examinations had ever been conducted.

Looking to address this, Barnes chose to address the long-held assumption that only smaller, dimmer stars could host orbiting planets that were tidally locked. He also considered other possibilities, which included slower or faster initial rotation periods as well as variations in planet size and the eccentricity of their orbits. What he found was that previous studies had been rather limited and only made allowances for one outcome.

As he explained in a University of Washington press statement:

“Planetary formation models, however, suggest the initial rotation of a planet could be much larger than several hours, perhaps even several weeks. And so when you explore that range, what you find is that there’s a possibility for a lot more exoplanets to be tidally locked. For example, if Earth formed with no Moon and with an initial ‘day’ that was four days long, one model predicts Earth would be tidally locked to the sun by now.”

From this, he found that potentially-habitable planets that orbit very late M-type (red dwarf) stars are likely to attain highly-circular orbits about 1 billion years after their formation. Furthermore, he found that for the majority, their orbits would be synchronized with their rotation – aka. they would be tidally-locked with their star. These findings could have significant implications for the study of exoplanets formation and evolution, not to mention habitability.

In the past, tidally-locked planets were thought to have extremes climates, thus eliminating any possibility of life. As an example, the planet Mercury experiences a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance, meaning it rotates three times on its axis for every two orbits it completes of the Sun. Because of this, a single day on Mercury lasts as long as 176 Earth days, and temperature range from 100 (-173 °C; -279 °F) to 700 K (427 °C; 800 °F) between the day side and the night side.

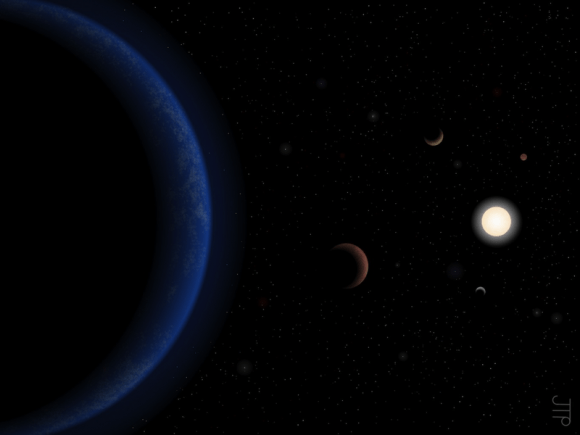

For a tidally-locked planets that orbit close to their stars, it was believed this situation would be even worse. However, astronomers have since come to speculate that the presence of an atmosphere around these planets could redistribute temperature across their surfaces. Unlike Mercury, which has no atmosphere and experiences no wind, these planets could maintain temperatures that would be supportive to life.

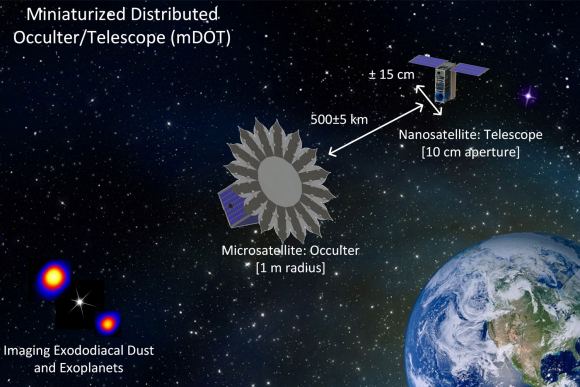

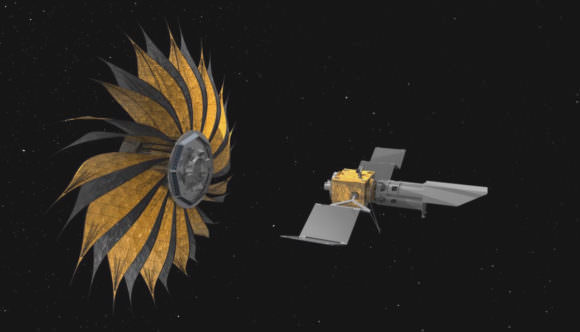

In any case, this study is one of many that is putting constraints on recent exoplanet discoveries. This is especially important given that the detection and study of extra-solar planets is still in its infancy, and limited to largely indirect methods. In other words, astronomers make estimates of a planet’s size, composition and whether or not it has an atmosphere based on transits and the influence these planets have on their stars.

In the coming years, next-generations missions like the James Web Space Telescope and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellites (TESS) are expected to improve this situation drastically. In addition to conducting more detailed observations on existing discoveries, they are also expected to uncover a wealth of more planets. If Barnes’ study is correct, the majority of those found will be tidally-locked, but that need not mean they are uninhabitable.

Prof. Barnes paper was accepted for publication by the journal Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. The research was funded by a NASA grant through the Virtual Planetary Laboratory.

Further Reading: University of Washington, arXiv