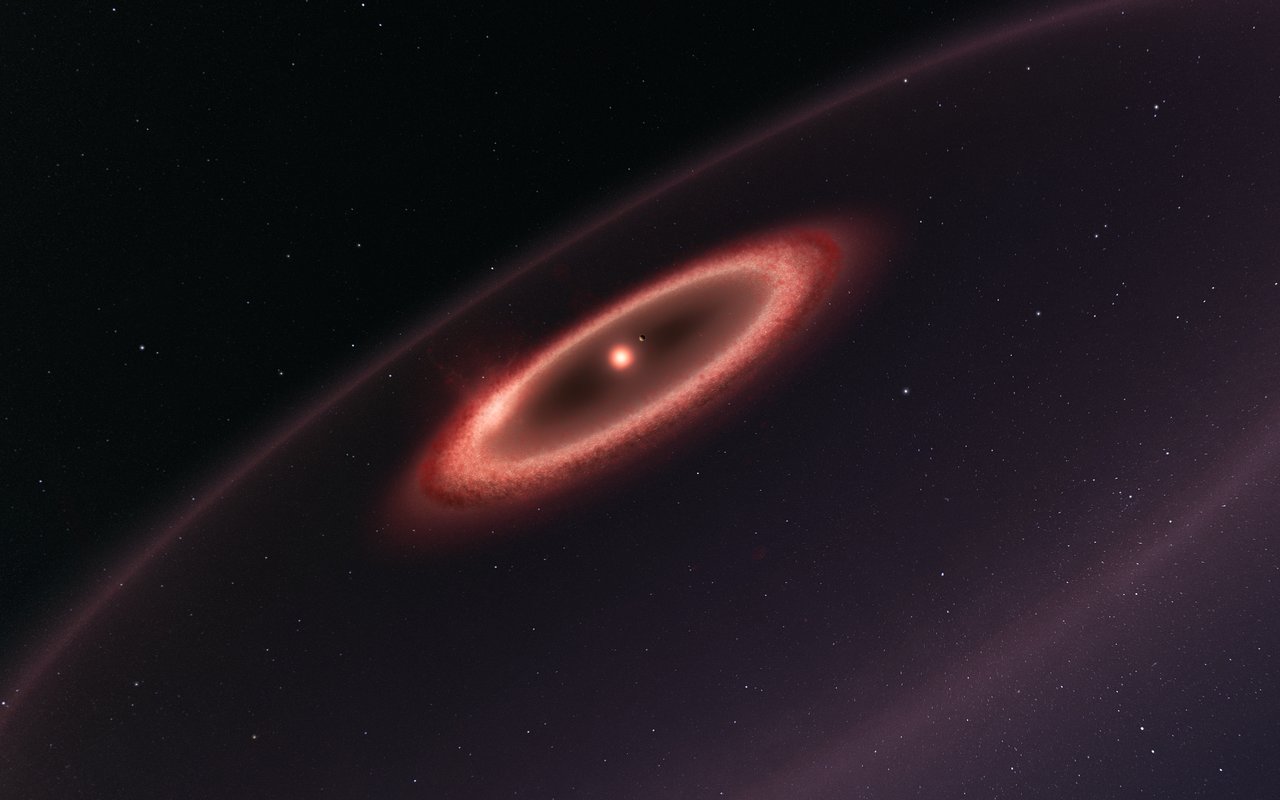

In August of 2016, the European Southern Observatory (ESO) announced the discovery of a terrestrial (i.e. rocky) extra-solar planet orbiting within the habitable zone of the nearby Proxima Centauri star system, just 4.25 light-years away. Naturally, news of this was met with a great deal of excitement. This was followed about six months later with the announcement of a seven-planet system orbiting the nearby star of TRAPPIST-1.

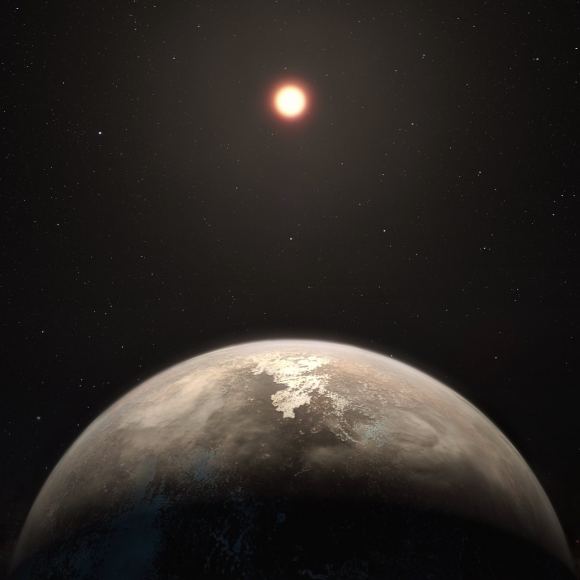

Well buckle up, because the ESO just announced that there is another potentially-habitable planet in our stellar neighborhood! Like Proxima b, this exoplanet – known as Ross 128b – is relatively close to our Solar System (10.8 light years away) and is believed to be temperate in nature. But on top of that, this rocky planet has the added benefit of orbiting a quiet red dwarf star, which boosts the likelihood of it being habitable.

The discovery paper, titled “A temperate exo-Earth around a quiet M dwarf at 3.4 parsecs“, was recently released by the ESO. The discovery team was led by Xavier Bonfils of the University of Grenoble Alpes, and included members from the Geneva Observatory, the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), the University of Buenos Aires, the University of Laguna, the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), and the University of Porto.

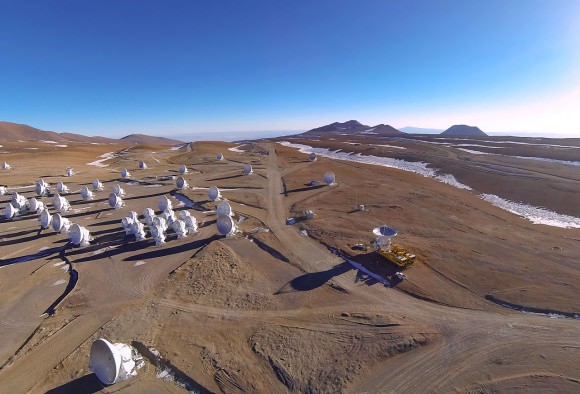

The discovery was made using the ESO’s High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS), located at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. This observatory relies on measurements of a star’s Doppler shift in order to determine if it moving back and forth, a sign that it has a system of planets. Using the HARPS data, the team determined that a rocky planet orbits Ross 128 (an M-type red dwarf star) at a distance of about 0.05 AU with a period of 9.9 days.

Despite its proximity to its host star, Ross 128b receives only 1.38 times more irradiation than the Earth. This is due to the cool and faint nature of red dwarf stars like Ross 128, which has a surface temperature roughly half that of our Sun. From this, the discovery team estimated that Ross 128b’s equilibrium temperature is likely somewhere between -60 and 20°C – i.e. close to what we experience here on Earth.

As Nicola Astudillo-Defru of the Geneva Observatory – and a co-author on the discovery paper – indicated in an ESO press release:

“This discovery is based on more than a decade of HARPS intensive monitoring together with state-of-the-art data reduction and analysis techniques. Only HARPS has demonstrated such a precision and it remains the best planet hunter of its kind, 15 years after it began operations.”

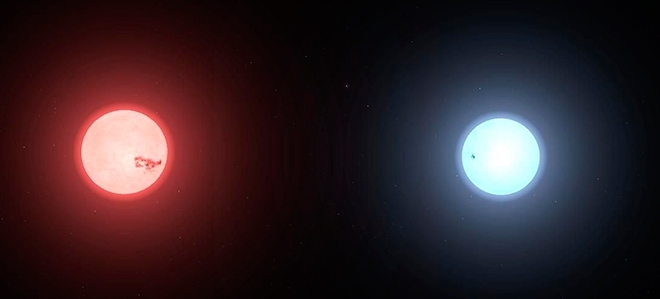

But what is most encouraging is the fact that Ross 128 is the “quietest” nearby star that is also home to an exoplanet. Compared to other classes of stars, M-type red dwarfs are particularly low in mass, dimmer and cooler. They are also the most common type of star in the Universe, accounting for 70% of the stars in spiral galaxies and more than 90% of all stars in elliptical galaxies.

Unfortunately, they are also variable and unstable compared to other classes of star, which means they experience regular flare ups. This means that any planets which orbit them will be periodically subjected to deadly ultraviolet and X-ray radiation. In comparison, Ross 128 is much quieter, meaning it experiences less in the way of flare activity, and planets orbiting it are therefore exposed to less radiation over time.

This means that, relative to Proxima b or those planets located within TRAPPIST-1’s habitable zone – Ross 128b is more likely to retain an atmosphere and support life. For those who are engaged in searches for exoplanets around M-type stars – or are of the opinion that red dwarfs are the best bet for finding habitable worlds – this latest discovery would seem to confirm that they are looking in the right spots!

As noted, red dwarfs are the most common in the Universe, and in recent years, many rocky planets (sometimes even a multi-planet system) have been found orbiting these stars. Combined with their natural longevity – which can remain in their main sequence phase for up to 10 trillion years – red dwarf stars have understandably become a popular target for exoplanet-hunters.

In fact, lead author Xavier Bonfils named their HARPS program “The Shortcut to Happiness” for this very reason. As he and his colleagues indicated, it is easier to detect small cool planets of Earth around smaller, dimmer M-type stars than it is around stars that are more similar to the Sun.

However, many in the scientific community have remained skeptical about the likelihood that any of these planets could be habitable (again, due to their variable nature). But this most recent discovery, along with recent research that indicates how tidally-locked planets that orbit red dwarf stars could hold onto their atmospheres, is another possible indication that these fears may be for naught.

Being at a distance of about 11 light-years from Earth, Ross 128b is currently the second-closest exoplanet to our Sun. However, Ross 128 itself is slowly moving closer towards us and will become our nearest stellar neighbor in roughly 79,000 years. At this point, Ross 128b will replace Proxima b and become the closest exoplanet to Earth!

But of course, much remains to be found about this latest exoplanet. While the discovery team consider Ross 128b to be a temperate planet based on its orbit, it remains uncertain as to whether it lies within, beyond, or on the cusp of the star’s habitable zone. However, further studies are expected to shed more light on this and other questions relating this potentially-habitable world.

Astronomers also anticipate that more temperature exoplanets will be discovered in the coming years, and that future surveys will be able to determine a great deal more about their atmospheres, composition and chemistry. Instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) are expected to play a major role.

Not only will these and other instrument help turn up more exoplanet candidates, they will also be used in the hunt for biosignatures in planet’s atmospheres (i.e. oxygen, nitrogen, water vapor, etc.). As Bonfils concluded:

“New facilities at ESO will first play a critical role in building the census of Earth-mass planets amenable to characterization. In particular, NIRPS, the infrared arm of HARPS, will boost our efficiency in observing red dwarfs, which emit most of their radiation in the infrared. And then, the ELT will provide the opportunity to observe and characterize a large fraction of these planets.”

At this juncture, the process of exoplanet discovery is moving beyond detection and getting into the process of characterization and detailed study. Even so, it is nice that we are still making groundbreaking discoveries in the field of detection. In the coming years, we may transition from looking for an Earth 2.0 to a point where weare actively studying several at once!