Solar sails have some major advantages over traditional propulsion methods - most notably they don’t use any propellant. But, how exactly do they turn? In traditional sailing, a ship’s captain can simply adjust the angle of the sail itself to catch the wind at a different angle. But they also have the added advantage of a rudder, which doesn’t work when sailing on light. This has been a long-standing challenge, but a new paper available in pre-print from arXiv, by Gulzhan Aldan and Igor Bargatin at the University of Pennsylvania describes a new technique to turn solar sails - kirigami.

Kirigami is an ancient Japanese form of paper cutting, similar to origami but intended to cut away the paper rather than fold it. In this particular case, it is intended to mechanically buckle the sail in a way that changes the angle the light reflects off it.

Traditionally this has been done one of three ways. Reaction wheels, which are also common on stationary satellites, are the most common way to “turn” a solar sail, but they require propellant and are extremely heavy, both of which limit the functionality of the sail itself. More recent advances include tip vanes, which are small, rotatable mirrors at the tips of the sail. Operating these is mechanically complex, and they can easily break down leaving the sail stranded in the direction its going.

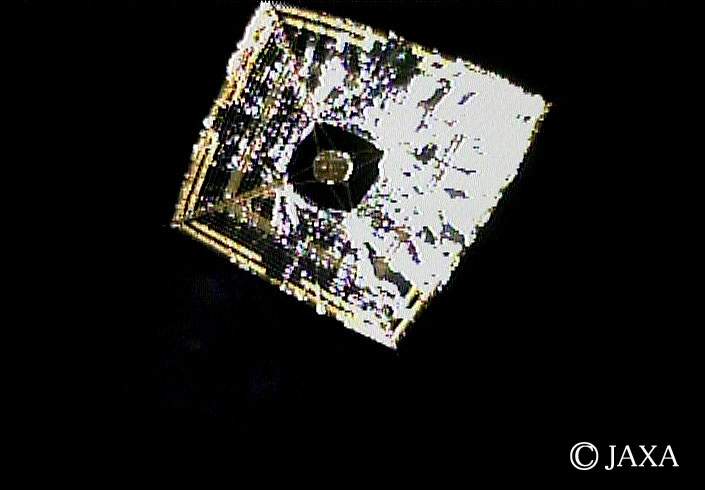

Fraser discusses the benefits of solar sails.Perhaps the most advanced idea are Reflectivity Control Devices (RCDs). Similar to what is seen on a Kindle reading display, these are liquid crystal panels that can switch between being reflective and absorptive to change the amount of energy the sail is using for momentum. While these are effective, they require power to maintain a constant state, draining a battery over time even when they are not operational.

The kirigami sail, in contrast, uses intentional “cuts” in the solar sail material. Each “unit cell” of a grid of solar sail panels is designed to contain some of these cuts running in axial and diagonal directions to the surface of the aluminized polyimide film, which is a standard material used in solar sails. When the film is pulled, the cuts allow the material to “buckle” - i.e. pop out of the plane that it’s being pulled in. This transforms the sail into a 3D surface where individual segments are tilted relative to the source of light.

These buckled sections act like thousands of tiny mirrors, bouncing light at a different angle of incidence depending on how steep their slope is. Due to conservation of momentum, the sail will be pushed in a direction opposite to where the light bounces towards, so each buckling segment can be tailored to pushing the overall sail in a particular direction.

Fraser explains what a solar sail actually does.While creating the buckling still requires some electrical power, it's only in the form of servo motors. These common components are designed to be power-efficient, but perhaps more importantly, they only use power when they are operating, unlike the RCDs used on the IKAROS mission in 2010.

To prove the system works as intended, the authors ran both a simulation and a physical experiment. The simulation used COMSOL, a standard physics simulation package, where they ran a series of ray tracing experiments and measured the forces on the sail with different buckling and solar angles. While the force on the system was measured to be small - 1 nN per Watt of sunlight - over time, that is more than enough to turn a small solar sail and its attendant payload.

To test the system in practice, the authors cut some film and put it in a test chamber with a laser. They then shined a laser on the film and then stretched it. Watching as the laser move across the wall of the chamber under different strains, the results matched the predicted angle of incidence for each strain level very well.

Ultimately, this technology could have an impact on the future of solar sailing by lowering the energy and propellant cost of its turning capabilities. But there are plenty of other competing technologies that are designed to provide the same thing, and unfortunately not a whole lot of experimental missions to test them. In other words, it might be a while before we see this technology in action in space. But when we do, the resulting sail will be sure to look astounding.

Learn More:

G. Aldan & I. Bargatin - Low-Power Solar Sail Control using In-Plane Forces from Tunable Buckling of Kirigami Films

UT - A Better Way to Turn Solar Sails

UT - Foldable Solar Sails Could Help With Aerobraking and Atmospheric Reentry

Universe Today

Universe Today