The Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer (SPHEREx), which launched back in May, was designed to explore the cosmos in optical and near-infrared light. Over its planned two-year mission, this observatory will observe the entire sky using a triple-mirror telescope and mercury-cadmium-telluride photodetector arrays, allowing it to gather data on more than 450 million galaxies, including the 100 million stars in the Milky Way, to explore the origins of the Universe.

On Dec. 18th, the mission released its first infrared map of the entire sky in 102 wavelengths, capturing parts of the Universe that are invisible to the naked eye. This data will help scientists address some of the greatest cosmological mysteries. These include how cosmic inflation in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang influenced the distribution of galaxies in our Universe. In addition, the data will shed light on how galaxies have evolved since and how the ingredients of life were distributed throughout the Milky Way.

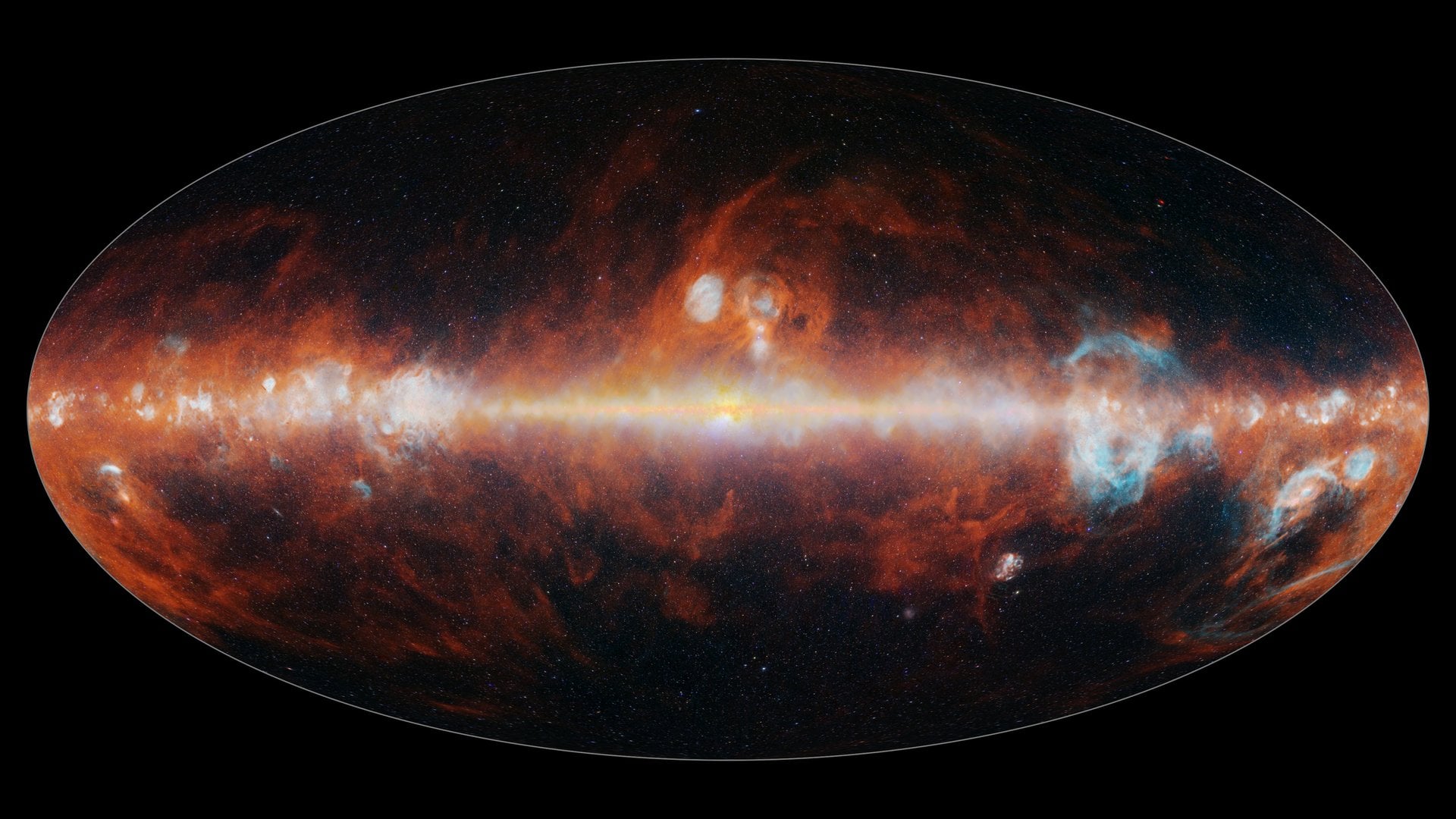

While the IR wavelengths are not visible to the naked eye, they are represented by different colors in the maps. The main image (shown above) shows hot hydrogen gas represented in blue, cosmic dust in red, and stars in green, blue, and white. Whereas some of the maps highlight distant galaxies and stars in the Milky Way's disk, with the wavelengths emitted by the dust and hot gas removed to make them more visible, others highlight nebulae and stellar nurseries and dust - like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), from which planets form.

Each wavelength provides unique information about the galaxies observed, their stars, and other features. SPHEREx relies on six detectors equipped with a specially designed filter to separate the light it gathers into different wavelengths. "The superpower of SPHEREx is that it captures the whole sky in 102 colors about every six months," said Beth Fabinsky, SPHEREx's project manager, in a NASA press release: "That’s an amazing amount of information to gather in a short amount of time. I think this makes us the mantis shrimp of telescopes, because we have an amazing multicolor visual detection system, and we can also see a very wide swath of our surroundings."

The mission builds on the work of previous observatories, such as NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), which have also mapped the entire sky. However, no other mission has done so in as many colors or with the same field of view as SPHEREx. The data it obtains will be used to measure distances to the more than 450 million galaxies observed, providing the first three-dimensional distance map of the cosmos. This will allow scientists to detect subtle variations in how galaxies are clustered and distributed throughout the cosmos.

The space telescope began observations in May and completed its first all-sky mosaic earlier this month. Every day, SPHEREx has observed another strip of the sky, taking about 3,600 images a day as it orbits Earth from pole to pole. Over the course of six months, the observatory has observed the full 360 degrees of the sky, capturing a massive trove of data and producing over 100 infrared maps. Said Shawn Domagal-Goldman, director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA HQ:

It’s incredible how much information SPHEREx has collected in just six months — information that will be especially valuable when used alongside our other missions’ data to better understand our Universe. We essentially have 102 new maps of the entire sky, each one in a different wavelength and containing unique information about the objects it sees. I think every astronomer is going to find something of value here, as NASA’s missions enable the world to answer fundamental questions about how the universe got its start, and how it changed to eventually create a home for us in it.

SPHEREx will complete three additional all-sky scans during its two-year primary mission, which will be merged to increase the sensitivity of its measurements. These measurements will offer insights into an event that took place one billionth of a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang and has not been repeated since. The first dataset has been made available to the public and can be accessed here.

Further Reading: NASA

Universe Today

Universe Today