Even most rocket scientists would rather avoid hard math when they don’t have to do it. So when it comes to figuring out orbits in complex three-body systems, like those in Cis-lunar space, which is between the Earth and the Moon, they’d rather someone else do the work for them. Luckily, some scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory seems to have a masochistic streak - or enough of an altruistic one that it overwhelmed the unpleasantness of doing the hard math - to come up with an open-source dataset and software package that maps out 1,000,000 cis-lunar orbits.

Note that the last paragraph didn’t say stable cis-lunar orbits. In fact, only 9.7% of them were “stable” over the six years the simulation was run. Others resulted in a satellite either crashing into the Moon, burning up in Earth’s atmosphere, or being ejected from the system entirely. So why is it so difficult to stay in orbit between the Earth and the Moon?

The Three-Body Problem is a popular Netflix series, based on a popular sci-fi book series, that is referencing an actual problem in physics. Systems where there are three bodies, each of which is both exerting gravity on, and being influence by the gravity of, the other two bodies, are known as being “chaotic”. Even one tiny change in the starting conditions of such a system or a slight deviation, such as getting hit by a solar storm, can cause massive and almost unpredictable changes in the orbital path of a satellite.

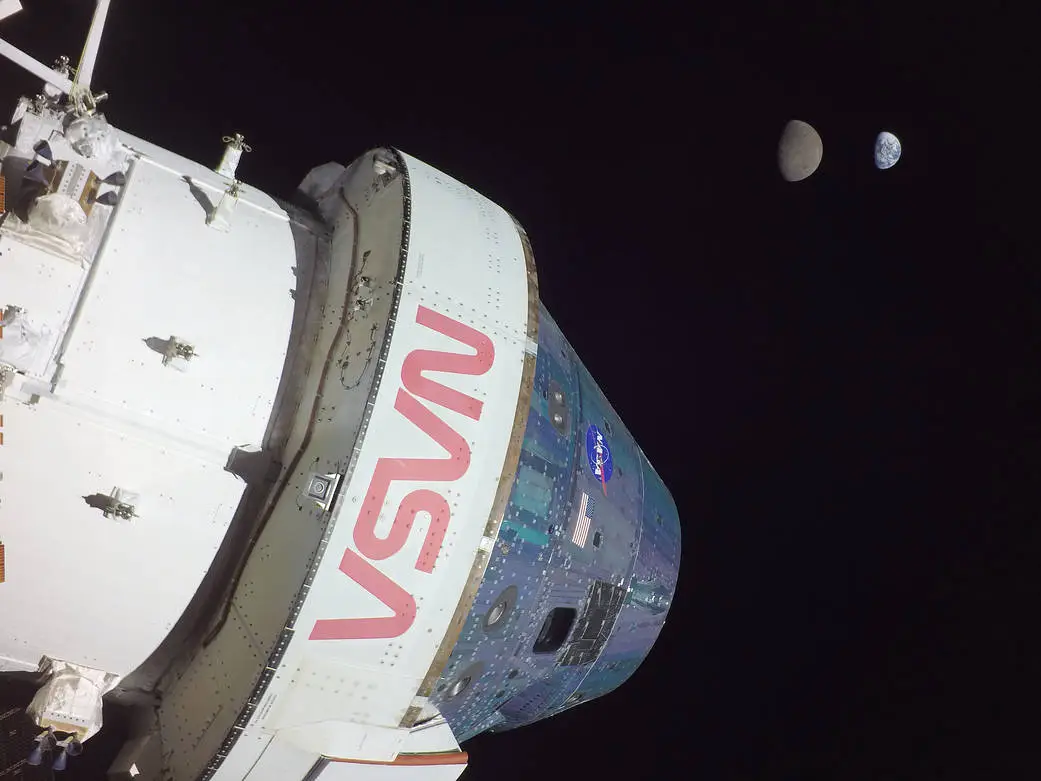

Fraser discusses the the Lunar Gateway, a critical piece of Artemis infrastructureBecause of that chaos, its been difficult to develop orbital paths for Moon missions. That is precisely what the new dataset/software is intended to solve. It provides a “Gold Standard” that can be used to prove/disprove navigational software or orbital planning systems on satellites. Those will become increasingly important as more and more organizations strive to use the space near the Moon to establish permanent bases and “Gateways” as the human presence in the system expands.

So how exactly does this data set work? Many advanced math problems have to start with a clearly defined set of “initial conditions” - in this can the LLNL scientists selected the position of the Sun, Earth, and Moon on January 1st, 1980 as their starting point, to ensure that anyone attempting to use the data has a clearly defined reference point. They then modeled a complex physics package of several forces acting on a satellite in Cis-lunar space for six years.

That physics package included gravity from each of the four systems - the Moon, the Earth, the satellite, and the Sun, which was modeled as a point source. It also included resonances between the Earth and the Moon, allowing it to capture some of the intricacies of what makes this math so difficult. In addition, it included thermal radiation pressure from the Earth, and solar radiation pressure from the Sun, both of which slowly pushes a satellite away from their respective sources, and adds even more complexity to the system.

Isaac Arthur discusses the usefulness of Cis-Lunar space. Credit - Isaac Arthur YouTube ChannelAs noted above, only about 97,000 of the 1,000,000 orbits the LLNL developed were stable - but there were notable clusters of stability located at certain areas. One such, unsurprisingly, was around the Lagrange points of the system - particularly L4 and L5, the leading and lagging Lagrange points of the Earth-Moon system. These can serve as gravitational “parking spots” for important infrastructure like the Lunar Gateway or similar equipment. Another stability point, which is slightly more surprising, was around a band about 5 times farther away than Geosynchronous Orbit. In this case, it appears the orbits are far enough away not to be completely beholden to Earth’s gravity, but also far enough from the Moon’s gravity not have it cause significant disruption to its orbital path.

National space agencies, and even militaries, might look to those islands of stability as critical parts of their future space endeavors. But as they begin to grow their presence there, they will likely refer back to this massive dataset release as part of their planning doctrine. Hopefully it will save them a ton of frustration trying to solve the math for themselves.

Learn More:

T. Yeager et al - An Open Benchmark of One Million High-Fidelity Cislunar Trajectories

UT - A Review of Humanity's Planned Expansion Between the Earth and the Moon

UT - U.S. Space Force CHPS to Patrol Around the Moon

UT - NASA Selects Six Companies to Provide Orbital Transfer Vehicle Studies

Universe Today

Universe Today