An annular eclipse crosses windswept remote Antarctica, heralding the first eclipse season of 2026.

Eclipse season is nigh. The first of two eclipse seasons for 2026 kicks off next week on Tuesday, February 17th, with an annular solar eclipse. And while solar eclipses often inspire viewers to journey to the ends of the Earth in order to stand in the shadow of the Moon, this one occurs over a truly remote stretch of the world, in Antarctica.

The antumbral shadow of the Moon just skims our planet on Tuesday, grazing the edge of the Antarctic continent. In fact, Antarctica is the only stretch of solid ground where annularity touches terra firma. Outside of the 616 kilometer wide track, the eclipse is partial only. The southern tip of South America, Africa and Madagascar are the only permanently populated areas that will witness a partial solar eclipse if skies are clear.

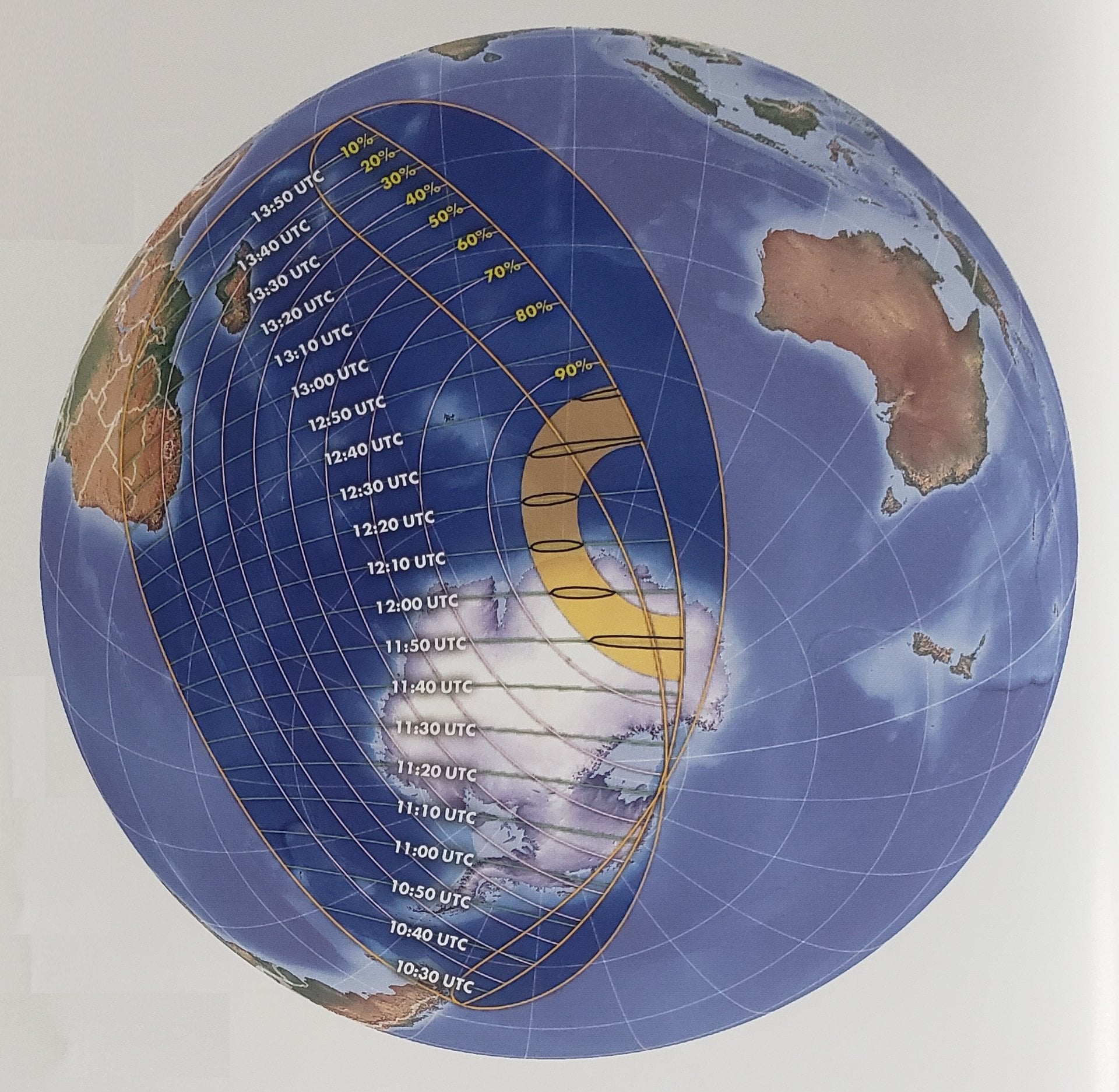

The footprint for Tuesday's annular solar eclipse. Credit: Atlas of Solar Eclipses 2020 to 2045 by Michael Zeiler and Michael Bakich.

The footprint for Tuesday's annular solar eclipse. Credit: Atlas of Solar Eclipses 2020 to 2045 by Michael Zeiler and Michael Bakich.

An annular eclipse occurs when the needle-thin shadow of the Moon doesn’t quite reach the Earth. This happens when the Moon is too far from the Earth in its elliptical orbit to fully cover the Sun. Though our fair planet just came off of perihelion on January 3rd, the Moon also just passed apogee earlier this week on February 10th.

Though there’s always talk about the ‘perfection’ of solar eclipses, we’re actually in an era where annulars are more common. This will become even more so in the future, as the Moon moves slowly away from the Earth. In about 600 million years time, a final brief total solar eclipse will grace the Earth one last time, after which, all eclipses of the Sun will be partial or annular only.

A recent study in the Journal of the British Astronomical Association on the frequency of solar eclipses from a given location on the Earth highlights this fact. On average, a given spot can expect to witness totality once every 373+/-7 years, while annulars occur more frequently, at an average of once every 226+/-4 years.

The penumbral shadow of the Moon touches down at 9:58 Universal Time (UT) off the southern tip of South America on February 17th, marking the start of partial phases for the eclipse. The annular action for the eclipse begins at 11:43 UT over central Antarctica, and ‘maximum annularity’ occurs shortly after at 12:11 UT, at 2 minutes and 20 seconds in duration. The eclipse shadow then sweeps out off the Antarctic coast, departing Earth at 12:41 UT over the southern Indian Ocean. Finally, the last partial phases end at 14:28 UT over the Indian Ocean, off the coast of Madagascar.

The eclipse has one thing going for it: it’s summertime in Antarctica. Two stations lie along the annular track: The European Space Agency’s Concordia Research Station and Russia’s Mirny Station. Both are occupied this time of year, and stand the best chance for humans to witness the ‘Ring of Fire’ that is an annular eclipse this coming Tuesday. Humans have witnessed totality from Antarctica before, back in 2003.

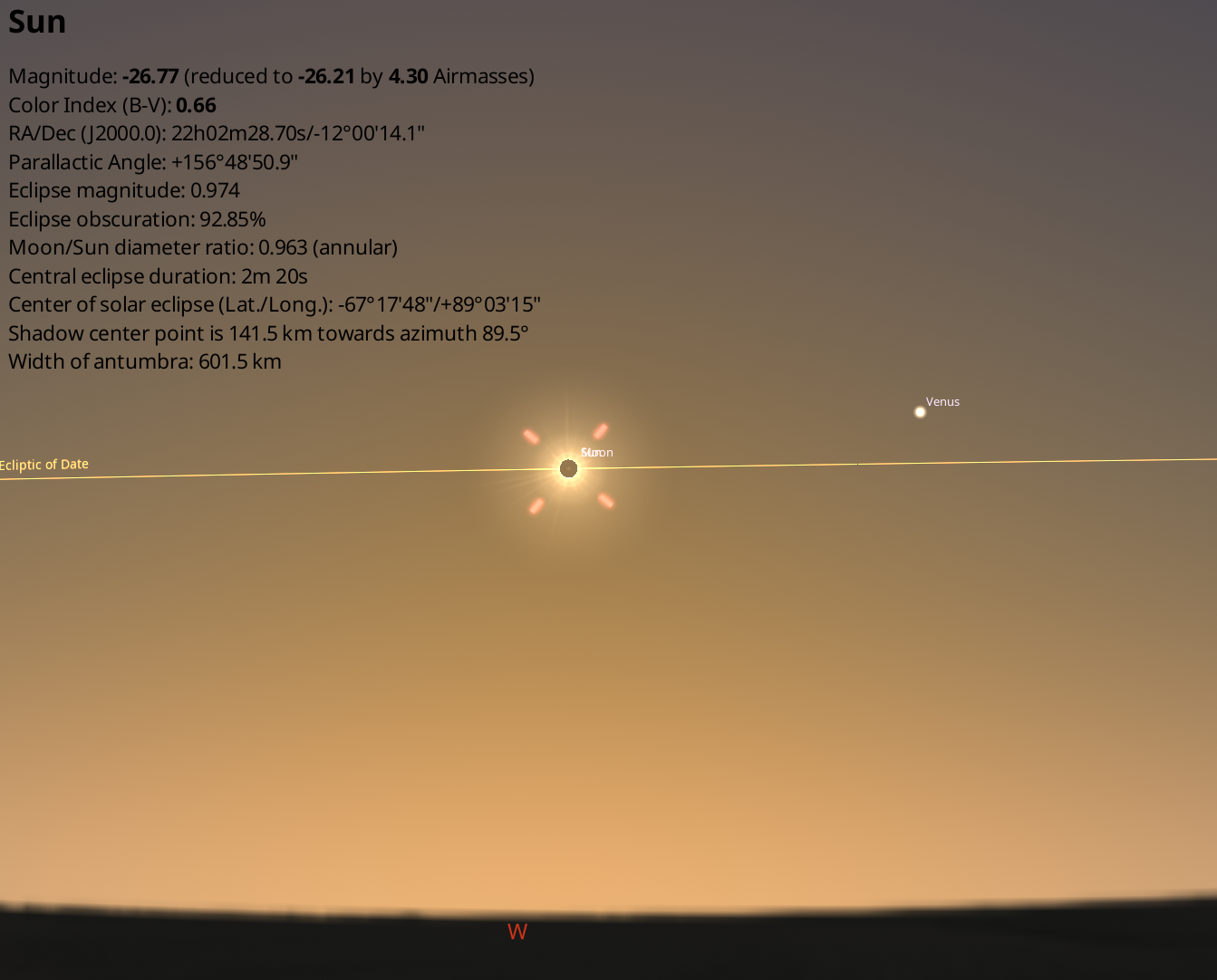

If you’re fortunate enough to see the annular eclipse, keep an eye out for -4th magnitude Venus, located about 10 degrees from the Sun.

Tuesday's annular eclipse versus Venus, as seen from the Antarctic coast. Credit: Stellarium.

Tuesday's annular eclipse versus Venus, as seen from the Antarctic coast. Credit: Stellarium.

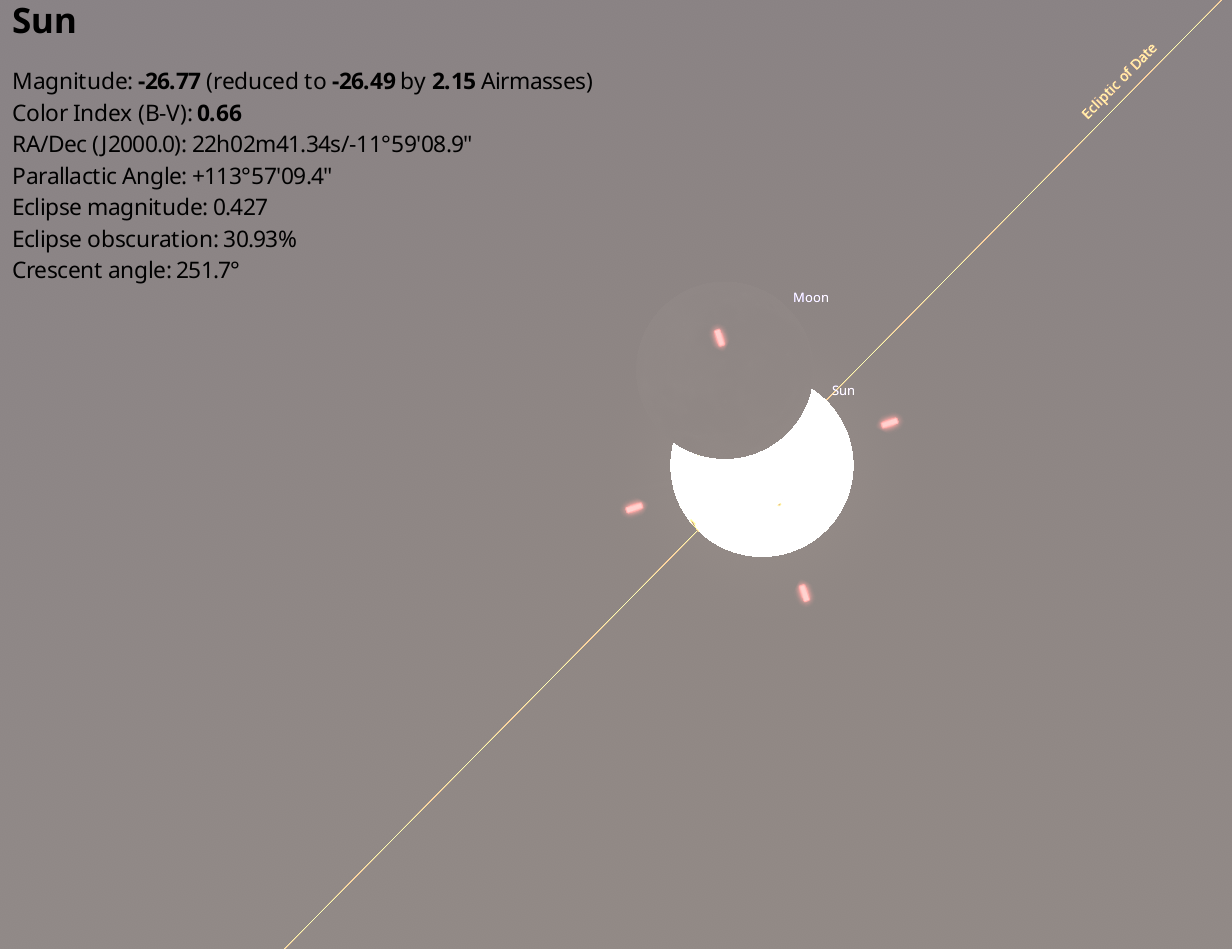

Prospects for South America and southern Africa are for a slight partial eclipse only. Cape Town, South Africa sees a 5% partial solar eclipse, while Tierra del Fuego and the southern tip of South America sees a 2% eclipse. The South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic sees a barely perceptible less than 1% eclipse. Madagascar gets a better view, with a 40% eclipse along its southeastern coast.

The point of maximum eclipse as seen from southern Madagascar. Credit: Stellarium.

The point of maximum eclipse as seen from southern Madagascar. Credit: Stellarium.

If skies are clear, regions along the Antarctic coast and far out to sea have a shot at an unforgettable sight: the glowing horns of the Sun, piercing the horizon. This can look as if a demon is about to emerge from the sea itself. If you didn’t know better, what would you make of such a sight?

Be sure to take proper eye and safety precautions during all phases of the eclipse, annular or partial. This means wearing eclipse glasses with the proper ISO 12312-2 certification, safely projecting the Sun or using a filter meant specifically for solar observing.

We’re still coming off of the peak for Solar Cycle 25, meaning that the prospects for a spotty photogenic Sun on Tuesday are pretty good. Too bad massive active region AR4366 has just rotated out of view, but a new massive group could always make itself known at any time.

For the rest of us, the best chance to ‘see’ the eclipse may come from space. NOAA’s GOES-East weather satellite offers full-disk views of the Earth, and I fully expect we’ll see the shadow nick the Earth in the satellite’s view on eclipse day.

2023's hybrid annular-total solar eclipse as seen from cis-lunar space, from the Hakuto-R lander. Credit: iSpace.

2023's hybrid annular-total solar eclipse as seen from cis-lunar space, from the Hakuto-R lander. Credit: iSpace.

I’m not seeing any webcasts featuring the eclipse live, but its not out of the realm of plausibility that some intrepid expedition might attempt this feat.

This eclipse is member 61 of the 71 eclipses in solar saros 121, which started all the way back on April 25th, 944 AD. This particular saros produced its last total solar eclipse on October 9th, 1809, and will produce its final brief partial solar eclipse on June 7th, 2206 AD.

An animation of Tuesday's eclipse. Credit: NASA/GSFC/A.T. Sinclair.

An animation of Tuesday's eclipse. Credit: NASA/GSFC/A.T. Sinclair.

Solar eclipses always occur at New Moon, and Tuesday’s New Moon sets at few interesting events in motion. First up, the sighting of the slim waxing crescent Moon on the evenings following Tuesday mark the start of Ramadan and the month of fasting and reflection on the Muslim calendar. The Full Moon on March 3rd is also the Paschal Moon leading up to Easter on April 5th, meaning it's also Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday and the start of Lent on the Gregorian Calendar next week.

Follow that Moon next week, as it groups with Mercury and Venus at dusk. The waxing crescent Moon actually occults Mercury on Wednesday night February 18th for the southeastern U.S., less than a day prior to Mercury reaching greatest elongation on the 19th.

Finally, this also sets us up for the bookend of the eclipse season, and something very special: a total lunar eclipse on March 3rd. This sees the return of totality for the Americas, the Pacific Ocean region, and eastern Asia and Australia.

And this is only eclipse season one of two, for 2026. The next season features a deep partial lunar eclipse on August 28th, preceded by one of the skywatching highlights for the year: a total solar eclipse next August 12th, with totality crossing Greenland, Iceland, the North Atlantic and northern Spain.

Eclipses almost always mean travel to the far flung corners of the globe, and a journey Tuesday’s annular eclipse would be the very pinnacle of astronomical adventure. While most of us will sit this one out, we can still marvel at how the clockwork gears of the Universe continue to turn, meshing the shadow of the Moon across the Earth.

Universe Today

Universe Today