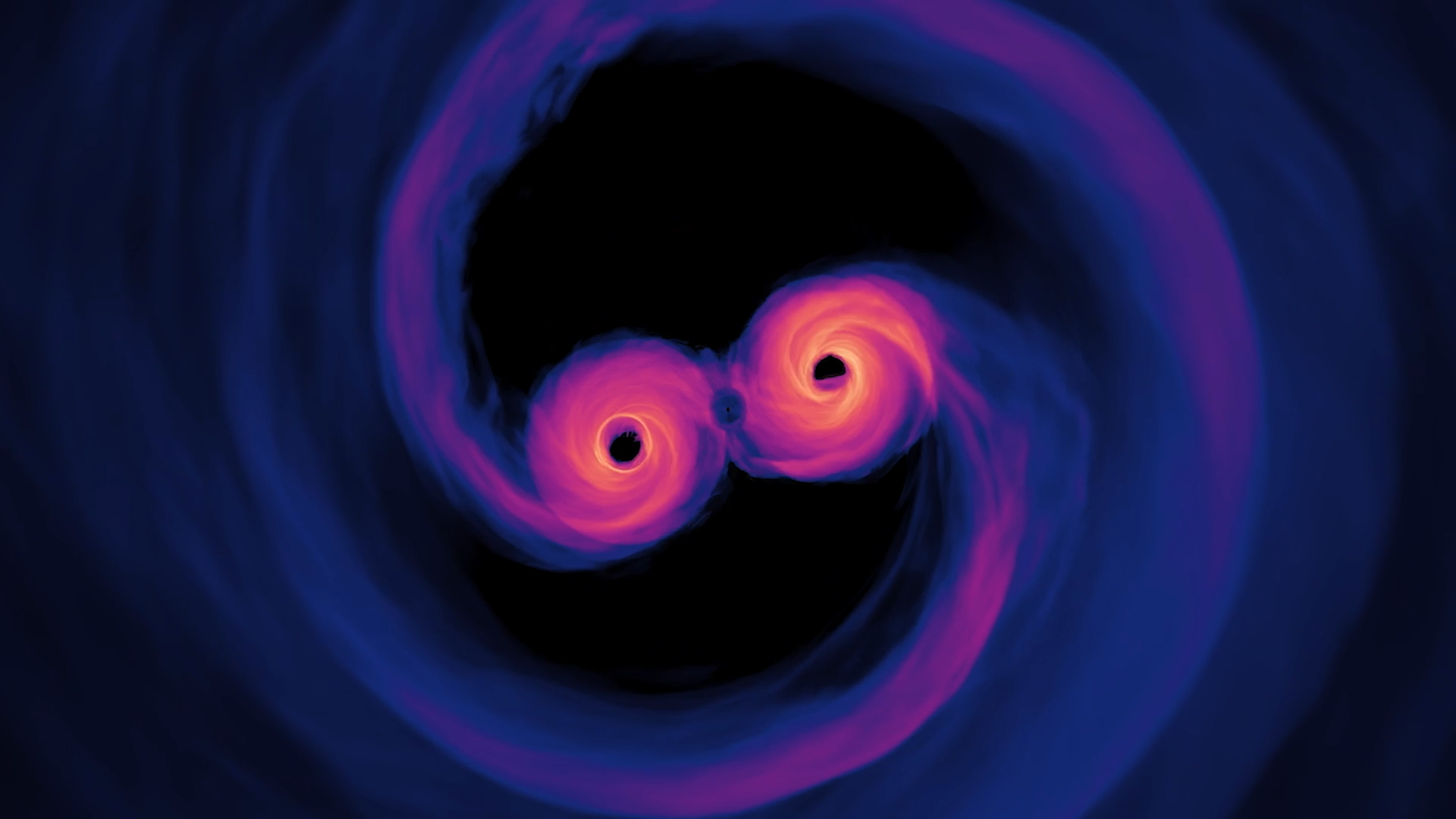

The universe is a big place, and tracking down some of the more interesting parts of it is tricky. Some of the most interesting parts of it, at least from a physics perspective, are merging black holes, so scientists spend a lot of time trying to track those down. One of the most recent attempts to do so was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters by the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav) collaboration. While they didn’t find any clear-cut evidence of continuous gravitational waves from merging black hole systems, they did manage to point out plenty of false alarms, and even disprove some myths about ones we thought actually existed.

NANOGrav isn’t your traditional gravitational wave detector. LIGO and its Earth-based brethren use long lasers to deter tiny interferences caused by gravitational waves moving the photons that make up the laser beam. NANOGrav takes a space-based approach and uses a series of 68 pulsars as their detectors. Pulsars are known for their regular timing, and any deviation from that could be caused by a gravitational wave - so finding regular, repeating patterns of a change in a pulsar’s timing would be pretty strong evidence for a continuous gravitational wave caused by a black hole merger.

Even with the help of the pulsars, searching the whole sky for potential sources of them would leave a lot of variables. So, the NANOGrav researchers decided to focus on a specific sub-set of plausible candidates that radio and visible light observations hinted might contain merging black holes. They came up with 114 galaxies that flickered in a regular pattern, and turned their attention to pulsars that could detect gravitational waves coming from those specific galaxies.

Fraser discusses what exactly gravitational waves are.The short answer of what they found is - nothing. But negative results in science can be exciting as well. In this case, they were able to disprove the existence of a merging black hole in the center of a galaxy known as 3C 66B - or at least constrain the mass of those merging black holes to something much smaller than originally thought. In addition, they did find two potentially interesting active galactic nuclei (AGNs), but they didn’t pass the ultimate statistical test to prove that they were actually a pair of merging black holes.

That didn’t stop them from giving them more personalized names though - so SDSS J1536+0441 became known as Rohan, after Rohan Shivakumar, a Yale undergraduate student who first analyzed the system. Given that there were only two really interesting candidates, and apparently someone in the NANOGrav collaboration is a Tolkien fan, the other interesting galaxy - SDSS J0729+4008, earned the name Gondor.

Rohan was actually the most interesting of the two, as it had previously been catalogued as having a “smoking gun” for a black hole binary in electromagnetic data by showing “double-peaked” emission lines. However, when Rohan ran the numbers on the pulsar data, it required a mass on the extremely high range of the possible sizes for the black holes. As a press release from Yale noted, this one is definitely worth following up on, though.

Fraser talks about how we can use gravitational waves to watch black hole collisions.Gondor, on the other hand, seemed to have regular periodicity of flickering pulsar light, but that faded over the course of the 15 year study. This particular target also was reliant on “noisy” pulsars to begin with, so the seemingly periodic signal might have just been noise in the end.

But, perhaps most importantly, this paper lays out a roadmap on how to use pulsars to detect binary black hole mergers. NANOGrav’s data is getting close to sensitive enough to pick up on these signals - and in some cases astronomers can even use it to confirm (or refute) findings from studies done with the electromagnetic spectrum. The authors think combining NANOGrav’s data with other pulsar sources, such as the International Pulsar Timing Array, will lead to a boost in sensitivity, and hopefully lead to the first confirmed detection of gravitational waves from an individual supermassive black hole binary in the coming years.

Learn More:

Yale - ‘The beacons were lit!’ A system to detect and map merging black holes

N. Agarwal et al. - The NANOGrav 15 yr Dataset: Targeted Searches for Supermassive Black Hole Binaries

UT - Black Hole Merger Provides Clearest Evidence Yet that Einstein, Hawking, and Kerr were Right

Universe Today

Universe Today