It's finally happened: Elon Musk has announced that SpaceX, the company he founded in 2002 with the goal of creating the first self-sustaining city on Mars, will no longer be focusing on Mars. As he announced on Feb. 8th via X, the social media platform he acquired in 2023, the company will now focus on creating a self-sustaining city on the Moon. Musk cited several reasons for this pivot, including a shorter development timeline ("less than 10 years, whereas Mars would take 20+ years"), faster transit times, and more regular launch windows.

While 135 million people worldwide tuned in to watch the Super Bowl, Musk typed out an auspicious message:

For those unaware, SpaceX has already shifted focus to building a self-growing city on the Moon, as we can potentially achieve that in less than 10 years, whereas Mars would take 20+ years. The mission of SpaceX remains the same: extend consciousness and life as we know it to the stars.

It is only possible to travel to Mars when the planets align every 26 months (six month trip time), whereas we can launch to the Moon every 10 days (2 day trip time). This means we can iterate much faster to complete a Moon city than a Mars city.

To Mars...

This represents a major departure for Musk, who has spent the past two decades working towards the singular goal of establishing an outpost of human civilization on Mars. In early 2001, Musk met Robert Zubrin (founder of the Mars Society) and gave a plenary talk at their fourth convention, where he first announced the Mars Oasis project. As he would later describe it, this project "would land a small robotic greenhouse that would establish life on another planet and show great images of green plants on a red background. It would get the public excited, and we'd learn a lot about what it takes to sustain plant life on the surface of Mars."

Loading tweet...

— View on Twitter

By 2012, during an [address made at the Royal Aeronautical Society in London] (https://www.space.com/18596-mars-colony-spacex-elon-musk.html), Musk outlined his vision for a self-sustaining city capable of supporting a population of 80,000. He was there to receive the Society's gold medal for his contributions to commercial space and share his plans for the future. Around the same time, Musk began offering teasers that his company planned to develop a super-heavy rocket capable of surpassing the Falcon 9 fleet's capabilities.

This became known as the Mars Colonial Transporter (MCT), formerly the BFR, a spacecraft designed to ferry passengers and cargo between Earth and Mars. In 2016, at the 67th International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Guadalajara, Mexico, Musk delivered his first annual update on the spacecraft's design, now renamed the Interplanetary Transport System (ITS). By 2019, the name was changed again to Starship and Superheavy, a name it has held ever since.

Since then, virtually all advances in terms of engine technology, flight testing, manufacturing, and materials science were directly tied to the launch vehicle's development. At the same time, Musk revealed that the Starship would rely on orbital refueling to reach Mars and how he envisioned a fleet of 1,000 Starship launches per year, each carrying 100 passengers or 100 metric tons of cargo.

...from the Moon?

For reasons that are not entirely obvious, SpaceX is now shifting its primary focus to the Moon. Musk provided all of the obvious benefits of this plan, claiming that a self-sustaining city could be built there in "less than 10 years, whereas Mars would take 20+ years." He also noted the difference in transit times and launch windows. Whereas missions to Mars can only occur every 26 months when the two planets are closest to each other (during a Mars Opposition), SpaceX would be capable of launching a lunar mission every 10 days.

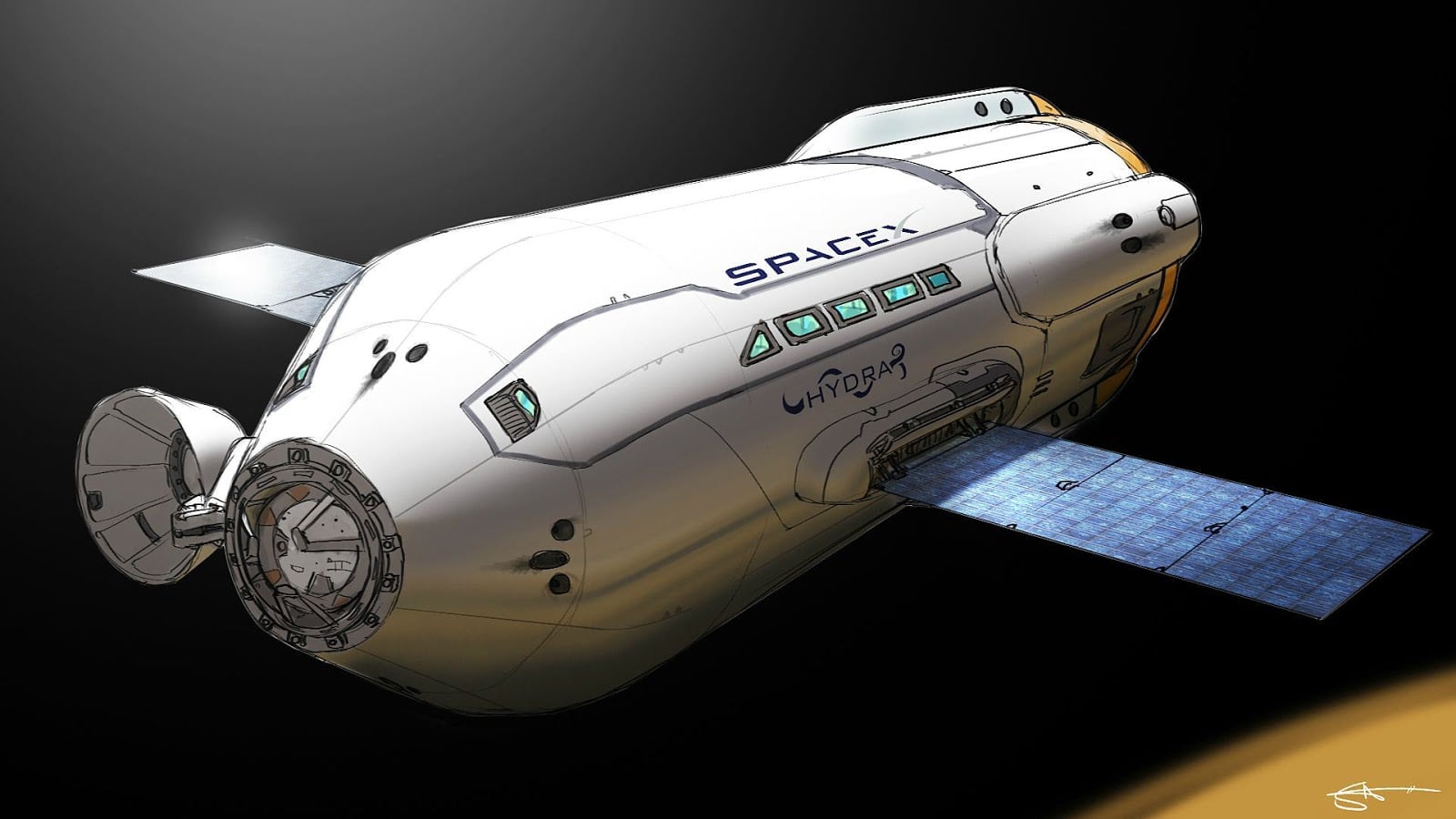

Concept art for SpaceX's Mars Colonial Transporter (MCT) Credit: Stanley Von Medvey (aka bagtaggar)

Concept art for SpaceX's Mars Colonial Transporter (MCT) Credit: Stanley Von Medvey (aka bagtaggar)

What's more, transits to the Moon are very rapid by comparison. Using conventional propulsion, it can take a spacecraft 6 to 9 months to reach Mars, whereas the Apollo missions took just 3 to 4 days to reach the Moon (Musk believes his rockets could make it in 2). That kind of launch cadence would certainly make the creation of a self-sustaining city on the Moon much easier and more cost-effective. However, Musk emphasized that SpaceX is not abandoning the idea of building a city on Mars; it is just being put on the back burner for now. As he wrote:

The mission of SpaceX remains the same: extend consciousness and life as we know it to the stars... SpaceX will also strive to build a Mars city and begin doing so in about 5 to 7 years, but the overriding priority is securing the future of civilization and the Moon is faster.

Why Now?

Naturally, there is the question of timing and why Musk is announcing this now. In the past, Musk has been dismissive about the potential for human habitats and commercial operations on the Moon. A little over a year ago, he went as far as to characterize the Moon as "a distraction" and reiterated his company's vision of going "straight to Mars." What exactly has changed in the past 14 months that would convince Elon to make such a seismic shift?

On the one hand, there have been setbacks in the development of the lunar lander version of the Starship (the Starship HLS), which is vital to NASA's [Artemis Program](https://www.nasa.gov/humans-in-space/artemis/). To date, the launch vehicle has conducted 11 flight tests, 5 of which failed, resulting in the loss of the spacecraft. In addition, the company has still not made an on-orbit refueling demonstration, which is also vital to Artemis.

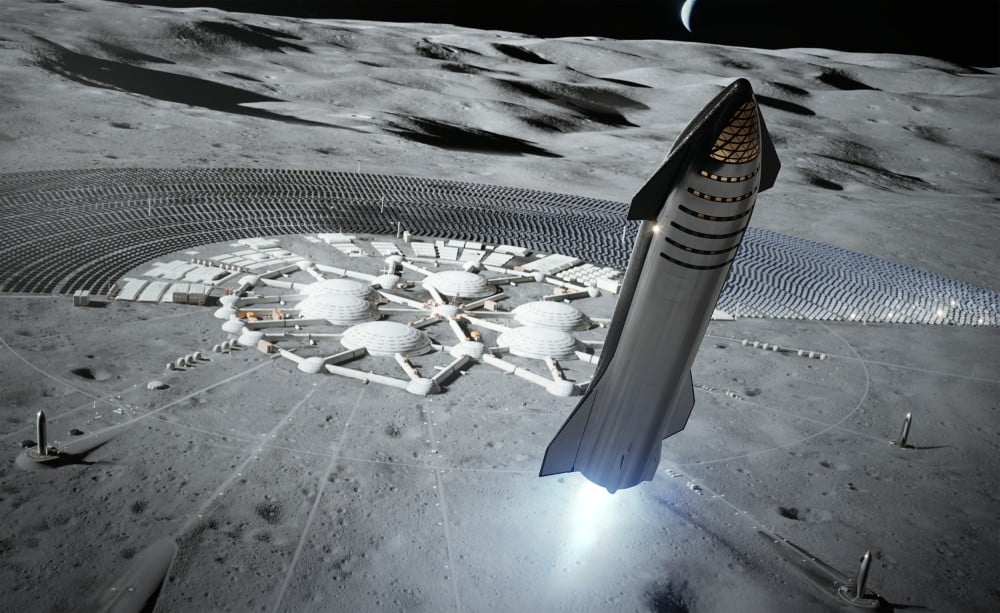

*A SpaceX Starship lifts off from a Mars base in this artist’s concept. Credit: SpaceX*

*A SpaceX Starship lifts off from a Mars base in this artist’s concept. Credit: SpaceX*

Faced with these obstacles, there is significant doubt that the Starship HLS will be ready in time for Artemis III, which is currently scheduled to launch next year. This is what led acting Administrator Sean Duffy to announce back in October that NASA was opening up the HLS contract to competition again. This does not bode well for Musk, who is already facing competition from Blue Origin (SpaceX's chief rival) for Artemis missions. At present, Jeff Bezos' has secured HLS contracts for Artemis V and VI using the company's Blue Moon lander.

SpaceX is also facing growing competition in the satellite launch market. While SpaceX has dominated this sector for many years, other companies and startups are capturing a growing share. In 2025, the total commercial space market was valued at $27.43 billion, with SpaceX accounting for 80% of the market share (roughly $22 billion). However, this was also the year that Blue Origin achieved its first orbital flight with the New Glenn rocket, which will make it a major contender in the satellite launch market. Rocket Lab is another rising star, specializing in low-cost launches servicing microsatellites.

For years, Musk has also focused on developing generative AI software integrated with his X social media platform. This plan has grown to include commercial space, as indicated by the recent merger of SpaceX and xAI. Musk announced that the "immediate focus" on the expanded company is deploying a constellation of up to one million satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). In so doing, Musk hopes to address a growing challenge for AI processing stations: rising electricity demand and the need for water to keep the equipment at operating temperature. As he wrote in a statement roughly a week ago:

By directly harnessing near-constant solar power with little operating or maintenance costs, these satellites will transform our ability to scale compute. It’s always sunny in space! Launching a constellation of a million satellites that operate as orbital data centers is a first step towards becoming a Kardashev II-level civilization, one that can harness the sun’s full power, while supporting AI-driven applications for billions of people today and ensuring humanity’s multiplanetary future.

By securing resources and launch capabilities on the Moon, SpaceX would be able to service and extend this constellation well beyond LEO. It's also consistent with the many recent discussions for "commercializing cis-lunar space," the next step beyond commercializing LEO. Between solar arrays in space, data centers, and an outpost on the Moon, SpaceX and other companies would effectively enable the extension of human civilization beyond Earth. For anyone hoping to live, work, and visit a city on the Moon, they could look forward to having abundant electricity and wireless internet on demand.

Conclusions?

Faced with these circumstances, Musk may be opting to shift his focus to smaller, more achievable goals. With the lunar market looming and Mars a much more distant prospect, he may also be hoping to beat his competitors to the punch. The mention of the Kardashev Scale in his statement is especially interesting, as it implies that these data centers would assist humanity in harnessing the power of the entire Solar System. Of course, Musk is known for his hyperbole and for statements that his plans are part of a massive effort to solve the world's problems and "save humanity."

But one cannot deny that this seismic shift is practical and likely driven by multiple factors. In reality, Musk is not stating anything new regarding the benefits he cited. For decades, space agencies and scientists alike have spoken of the importance of lunar exploration and settlement before going to Mars. Famed Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield summed it up perfectly when he said, "[O]ur efforts should be focused on renewed exploration of the Moon and the creation of a lunar settlement before we do the same for Mars."

This is also the rationale behind NASA's "Moon to Mars" mission architecture, which it has pursued ever since the Constellation Program (2005-2010). For Musk, this may be a case of reading the writing on the wall after years of having to push back the start date for his proposed Martian city. Only time will tell.

Universe Today

Universe Today