When we think of ice on Mars, we typically think of the poles, where we can see it visibly through probes and even ground-based telescopes. But the poles are hard to access, and even more so given the restrictions on exploration there due to potential biological contamination. Scientists have long hoped to find water closer to the equator, making it more accessible to human explorers. There are parts of the mid-latitudes of Mars that appear to be glaciers covered by thick layers of dust and rock. So are these features really holding massive reserves of water close to where humans might first step foot on the Red Planet? They might be, according to a new paper from M.A. de Pablo and their co-authors, recently published in Icarus.

The key might be a small, volcanic island in Antarctica. Known as Deception Island, it’s a volcano that has covered some massive glaciers surrounding it with ash and dust from a series of eruptions in the 60s and 70s. The authors think they found a volcano on Mars with a similar history known as Hecates Tholus.

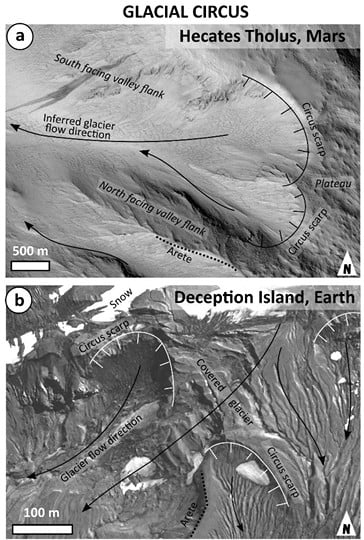

Hecates Tholus is an ancient shield volcano on Mars that has many of the same features as the Deception Island volcano. And since we know there’s ice settled under the debris in Antarctica, it would imply that similar features might be underlying the debris surrounding Hecates Tholus.

Fraser discusses where water might be hiding on MarsThere are several “smoking gun” features on Mars that strongly suggest the presence of glacial ice rather than just loose rock, or even rock that is cemented together with a small amount of ice. First are the crevasses. Any explorer will tell you how absurdly dangerous these features are on Earth, but the key feature of the ones on Deception Island is that they’re visible from Space, particularly near what are known as the “headwalls” of the glacier - the sheer, near-vertical cliff that features as the uppermost end of a glacier. Similar features are noticeable from space at Hecates Tholus, and such clear, visible fractures wouldn’t be noticeable if it were simply rock underlying them. Specifically, these crevasses mean a solid ice core is still moving underneath the debris surface from the volcano.

Another smoking gun is the presence of bergschrunds. These are distinct, deep cracks that form at the top of a glacier. All bergschrunds are technically a type of crevasse, though they are much larger and created by a very specific process compared to typical examples. That process is the separation of moving from stagnant ice. Some examples of bergschrunds near Hecates Tholus run up to 600m long, and are a clear indication that, at least at one point, there was active ice movement.

A final point of evidence is the bulldozer effect - or more specifically the presence of “push moraines” at the bottom of the valleys of both Deception Island and Hecates Tholus. When they’re moving, glaciers act as bulldozers, pushing massive rocks in front of them and leaving behind bumpy terrain. Similar shapes to those seen on Deception Island are again visible surrounding Hecates Tholus, indicating that, at some point, there was an active glacier in the area.

Fraser talks about the restriction of exploration missions to the Martian South Pole.So if these glaciers do exist, how did they survive for millions of years without evaporating? The authors propose a two-stage process. First, when crevasses formed, some of the water did sublimate away, but those holes were then coated with dust, protecting the newly exposed water from further sublimation. Eventually, this resulted in the shallow “troughs” that are what we actually see on Mars instead of true crevasses.

One obvious question for the people playing close attention to Martian exploration is - why didn’t SHARAD see anything there. If a sub-surface glacier exists at the equator, surely the ground penetrating radar on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter would be able to pick up a signal from it. After all, we’ve repeatedly reported on it doing so in other Martian regions (and occasionally having to “update” those discoveries). The physics of SHARAD’s radar does not operate well on the steep slope of volcanoes, making it difficult to get a clear picture of whatever is located under the dust and debris. To truly get a better understanding we will need samples on the ground, whether from robots or humans.

But there’s another, unspoken implication as part of the paper. If Mars truly does have huge glaciers hiding near Hecates Tholus, it might have plenty of other ones hiding near other massive volcanoes as well. Article IX of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty requires exploration of other solar system bodies to avoid “harmful contamination” of celestial bodies. Many people have interpreted that clause as requiring explorers to avoid the Martian poles, where there is evidence of plenty of water. If there turns out to be water all over Mars, buried under debris from volcanoes, does that now mean that those areas are off-limits to explorers as well?

Only time will tell for that answer - and we may never actually know if there is water surrounding these volcanoes unless we actually send explorers there - there’s only so much we can do remotely. There are some proposals for missions that could settle the debate, such as FlyRADAR, but for now, we will have to wait for definitive word of whether Martian volcanoes are covered in glaciers - and maybe take a look at a Deceptive one in our own neck of the woods in the meantime.

Learn More:

M. A. de Pablo et al. - Debris-covered glaciers on deception island (Antarctica) as analogues for possible glaciers on the lower northwest flank of Hecates Tholus volcano, Mars

UT - Mars Glaciers Have More Water Content than Previously Thought

Universe Today

Universe Today