The Milky Way's galactic center should be home to many pulsars, but for some reason, we can't find them. New research identified a candidate pulsar very near the MW's center. If it can be confirmed, it's a chance to test General Relativity.

The tentative discovery comes from the Breakthrough Listen Galactic Center Survey. It's one of the most sensitive searches for pulsars in the Milky Way's complex central region.

The discovery is in a paper titled "On the Deepest Search for Galactic Center Pulsars and an Examination of an Intriguing Millisecond Pulsar Candidate." It's published in The Astrophysical Journal, and the lead author is Karen Perez. Perez is a recent PhD graduate from Columbia University.

The research is based on about 20 hours of galactic center (GC) observations with the Green Bank Telescope, a radio telescope in West Virginia. The search was sensitive to the most luminous pulsars that astrophysicists expect to find there. "Among 5282 signal candidates, we identify an interesting 8.19 ms MSP candidate..." the paper's authors write. They explain that the source was consistent across a 1 hour scan. "We are unable to make a definitive claim about the candidate due to a mixed degree of confidence from these tests and, more broadly, its nondetection in subsequent observations," they explain.

There's a persistent missing pulsar problem when it comes the the Milky Way's GC. Despite repeated efforts, and despite the fact that the region is densely-packed with stars and should be teeming with pulsars, only a few have ever been detected. "This deepens the ongoing missing pulsar problem in the GC, reinforcing the idea that strong scattering and/or extreme orbital dynamics may obscure pulsar signals in this region," the authors write.

The Milky Way's galactic center is packed with stars, as this infrared image from the Spitzer Space Telescope shows. Many of the stars will be massive ones that explode as supernovae. Since pulsars are neutron stars, and neutron stars come from supernovae, there should be plenty of pulsars in the region. But only a few have been identified. Image Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech, Susan Stolovy (SSC/Caltech) et al.

The Milky Way's galactic center is packed with stars, as this infrared image from the Spitzer Space Telescope shows. Many of the stars will be massive ones that explode as supernovae. Since pulsars are neutron stars, and neutron stars come from supernovae, there should be plenty of pulsars in the region. But only a few have been identified. Image Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech, Susan Stolovy (SSC/Caltech) et al.

The candidate is named BLPSR, for Breakthrough Listen Pulsar. If this one is confirmed, it could illuminate the limitations or problems of our search methods and potentially open a floodgate of other discoveries.

But finding this one could also be a real gift to scientists for another reason. Pulsars are sometimes called cosmic lighthouses. They're highly magnetized neutron stars that rotate rapidly. They emit electromagnetic radiation from their poles, and when their poles are pointed at Earth, we can see the radiation. The radiation signal flickers in and out of view as they rotate. This one is a millisecond pulsar (MSP) with a frequency of 8.19 ms between signals. It's location near Sagitarrius A-star, the Milky Way's SMBH, is fortuitous.

There are six known pulsars near the GC, but none of them are close enough to test GR. "While these discoveries support the presence of a large pulsar population near the GC, none lie close enough (within a parsec) to the SMBH to probe its gravitational field," the authors write. They're so far from the SMBH that they don't even appear in this survey.

If BLPSR can be confirmed, then it can be used to test General Relativity.

"Any external influence on a pulsar, such as the gravitational pull of a massive object, would introduce anomalies in this steady arrival of pulses, which can be measured and modeled," said study co-author Slavko Bogdanov in a press release. Bogdanov is a research scientist at the Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory. “In addition, when the pulses travel near a very massive object, they may be deflected and experience time delays due to the warping of space-time, as predicted by Einstein's General Theory of Relativity.”

This configuration—an extremely precise clock closely orbiting an extreme gravitational environment— would allow "unprecedented tests" of GR. For the first time, scientists could obtain precise measurements of space-time near supermassive black holes. This is an extremely important and long term goal of studying the galactic center. Any deviations in the timing of the pulsar's signal tells us about the space-time. It would let physicists measure frame-dragging and also test the no-hair theorem, among other things.

The problem is, while BLPSR was detected once, it didn't appear in subsequent efforts. The researchers explain that the signal could've arisen from background noise. "In light of these factors—and given the extraordinary implications of detecting a pulsar near Sgr A*—we remain highly skeptical of BLPSR and emphasize that a much stronger burden of proof is required before asserting its astrophysical origin."

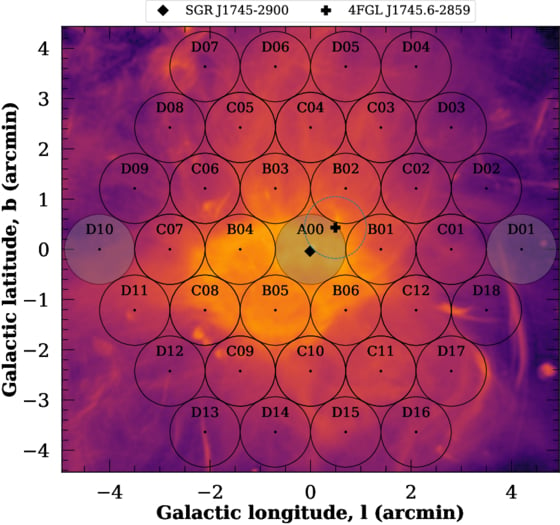

*This figure shows the pointings from the Breakthrough Listen Galactic Center survey. The black diamond represents the location of the known GC magnetar, J1745–2900, near the SMBH Sgr A*. The black cross shows a bright gamma-ray point source thought to be the high-energy counterpart to the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A-star. The region should be teeming with pulsars but isn't. Image Credit: Perez et al. 2026. ApJ*

*This figure shows the pointings from the Breakthrough Listen Galactic Center survey. The black diamond represents the location of the known GC magnetar, J1745–2900, near the SMBH Sgr A*. The black cross shows a bright gamma-ray point source thought to be the high-energy counterpart to the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A-star. The region should be teeming with pulsars but isn't. Image Credit: Perez et al. 2026. ApJ*

Breakthrough Listen is releasing their data so that other researchers can pore over it. The researchers are also looking ahead to more sensitive surveys of the GC.

“We’re looking forward to what follow-up observations might reveal about this pulsar candidate,” lead author Perez said. "If confirmed, it could help us better understand both our own Galaxy, and General Relativity as a whole.”

Future observations are needed, and the authors point out that the Square Kilometer Array could be able to detect and confirm pulsars in the GC.

"Detecting, confirming, and timing a pulsar in a close orbit around Sgr A* remains a major goal for testing general relativity, understanding the SMBH, and probing the dense and turbulent environment at the heart of our Galaxy," the authors write. "Such surveys will ultimately reveal the long-hypothesized pulsar population or further deepen the missing pulsar problem in the GC," they conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today