Astronomers know that supermassive black holes (SMBH) can inhibit star formation. These behemoths, which seem to be present in the center of large galaxies like ours, inject energy into their surroundings, heating up star-forming gas. Gas needs to be cool to collapse and form stars, so active SMBH put a damper on the process.

This is called black hole feedback, and it's an active area of research.

But new research extends this phenomenon. It shows that rather than only inhibiting star formation in their own galaxies, SMBH can actually suppress the process in surrounding galaxies. While astrophysicists have observed quasars—which are extremely luminous and active SMBH—ionizing intergalactic diffuse hydrogen, this research extends the idea into star formation in other galaxies.

The work is titled "Quasar Radiative Feedback May Suppress Galaxy Growth on Intergalactic Scales at z = 6.3" and it's published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The lead author is Yongda Zhu. Zhu is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Arizona Department of Astronomy and Steward Observatory.

"We present observational evidence that intense ionizing radiation from a luminous quasar suppresses nebular emission in nearby galaxies on intergalactic scales at z = 6.3," the researchers explain in their paper. A redshift of 6.3 indicates this object is being observed only about 900 million years after the Big Bang, during the Epoch of Reionization (EOR). The research is based on the quasar J0100+2802, the most UV luminous quasar in this epoch.

When the authors say that radiation from the quasar "suppresses nebular emission in nearby galaxies," they're referring to doubly-ionized oxygen [O iii]. In this case, it's [O iii] λ5008, one of the brightest emission lines in star-forming regions. While stars form when clouds of molecular hydrogen collapse, [O iii] comes from hot young stars, whose powerful UV ionizes oxygen. In essence, it traces the effect of UV radiation from the quasar on star-forming gas in nearby galaxies. In this case, they're referring to other galaxies in a group with the quasar's galaxy.

*This is a JWST NIRCam image of Quasar SDSS J0100+2802 and other distant galaxies of various types. SDSS J0100+2802 is a hyperluminous quasar that's 40,000 times more luminous than all the stars in the Milky Way. That overpowering energy has far-reaching consequences. Image Credit: By ESA/Webb - https://esawebb.org/images/EIGER1/, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=170756442*

*This is a JWST NIRCam image of Quasar SDSS J0100+2802 and other distant galaxies of various types. SDSS J0100+2802 is a hyperluminous quasar that's 40,000 times more luminous than all the stars in the Milky Way. That overpowering energy has far-reaching consequences. Image Credit: By ESA/Webb - https://esawebb.org/images/EIGER1/, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=170756442*

These results are based on JWST observations, and they help explain some other, separate observations with the space telescope. Those previous observations showed that in the early Universe, fewer galaxies surrounded brilliant quasars. This was counter to the norm, where galaxies are found in groups. Why would early quasar galaxies be found alone?

"We were puzzled," said Zhu, "Was the expensive JWST broken?" he added with a laugh. "Then we realized the galaxies might actually be there, but difficult to detect because their very recent star formation was suppressed."

The researchers decided to study J0100+2802 to test the idea. It's extremely bright in UV, and is powered by a supermassive black hole with about 12 billion solar masses.

The heart of this research is in comparing the UV-induced [O iii] with the UV continuum in the neighbouring galaxies. The UV continuum remains fairly constant regardless of distance from the quasar, while the [O iii] decreases. Since [O iii] traces recent star formation, decreased [O iii] indicates suppressed recent star formation. In a nutshell, this shows that the quasar is ionizing star-forming gas in the neighbouring galaxies, preventing it from forming stars.

"Traditionally, people have thought that because galaxies are so far apart, they evolve largely on their own," lead author Zhu said in a press release. "But we found that a very active, supermassive black hole in one galaxy can affect other galaxies across millions of light-years, suggesting that galaxy evolution may be more of a group effort."

"An active supermassive black hole is like a hungry predator dominating the ecosystem," he said. "Simply put, it swallows up matter and influences how stars in nearby galaxies grow."

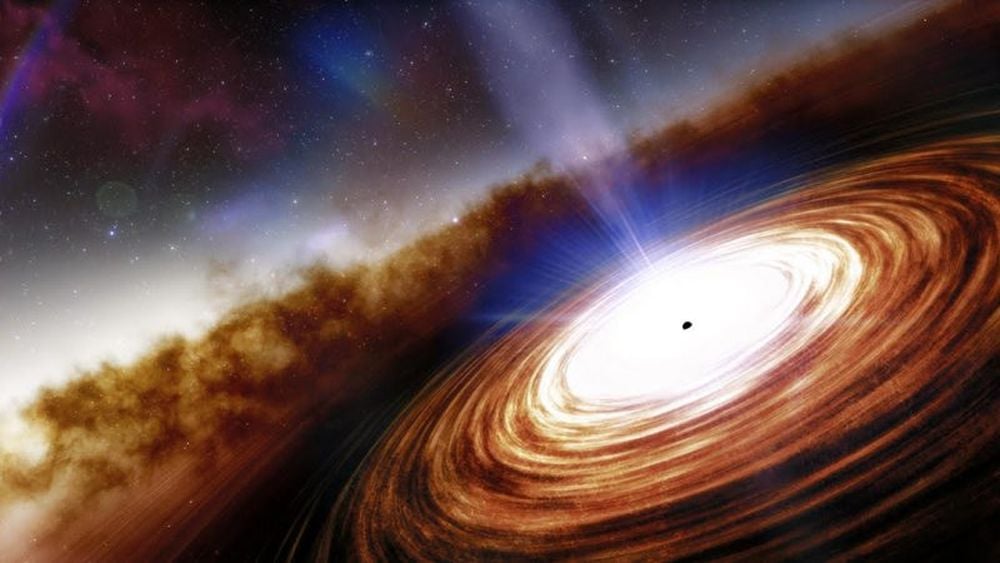

While quasars can emit powerful, energetic jets into their surroundings, that's not the source of radiation in this work. Instead it comes from superheated material in the supermassive black hole's accretion disk. That disk acts like an extremely energetic UV floodlight that suppresses star formation in nearby galaxies. Image Credit: NOIRLab/ NSF/ AURA/ J. da Silva/ Keck Observatory.

While quasars can emit powerful, energetic jets into their surroundings, that's not the source of radiation in this work. Instead it comes from superheated material in the supermassive black hole's accretion disk. That disk acts like an extremely energetic UV floodlight that suppresses star formation in nearby galaxies. Image Credit: NOIRLab/ NSF/ AURA/ J. da Silva/ Keck Observatory.

"Black holes are known to 'eat' a lot of stuff, but during the active eating process and in their luminous quasar form, they also emit very strong radiation," said Zhu. "The intense heat and radiation split the molecular hydrogen that makes up vast, interstellar gas clouds, quenching its potential to accumulate and turn into new stars."

We probably shouldn't be surprised that an extraordinarily massive and extremely luminous, energetic object can have far-reaching effects. We're only infants in this Universe, and we're bound to keep discovering how things work on such a massive scale.

"For the first time, we have evidence that this radiation impacts the universe on an intergalactic scale," said Zhu, "Quasars don't just suppress stars in their host galaxies, but also in nearby galaxies within a radius of at least a million light-years."

"These results are consistent with a scenario in which quasar radiation rapidly alters ISM conditions, likely through H2 photodissociation or ionization, suppressing recent star formation without immediately affecting the UV-bright stellar population," the authors write. "JWST provides direct constraints on such radiative feedback during reionization, offering a window into quasar–galaxy interaction at the highest redshifts."

These results are intriguing, but they're based on a sample of one. The next step is to test this idea against other quasars from the early Universe. The authors say that the JWST can do this wide-field NIRCam imaging and NIRSpec follow-up observations.

It's possible that our own Milky Way galaxy had a quasar at one time, and it's instinctive to wonder if it may have had a suppressing effect on star-formation in nearby galaxies, as well as in the MW itself. But we may never know.

"Understanding how galaxies influenced one another in the early universe helps us better understand how our own galaxy came to be," Zhu said. "Now we realize that supermassive black holes may have played a much larger role in galaxy evolution than we once thought – acting as cosmic predators, influencing the growth of stars in nearby galaxies during the early universe."

Universe Today

Universe Today