It feels like every time we publish an article about an exciting discovery of a potential biosignature on a new exoplanet, we have to publish a follow-up one a few months later debunking the original claims. That is exactly how science is supposed to work, and part of our job as science journalists is to report on the debunking as well as the original story, even if it might not be as exciting. In this particular case, it seems the discovery of dimethyl sulfide in the atmosphere of exoplanet K2-18 b was a false alarm, according to a new paper available in pre-print form on arXiv by Luis Welbanks of Arizona State University and his co-authors.

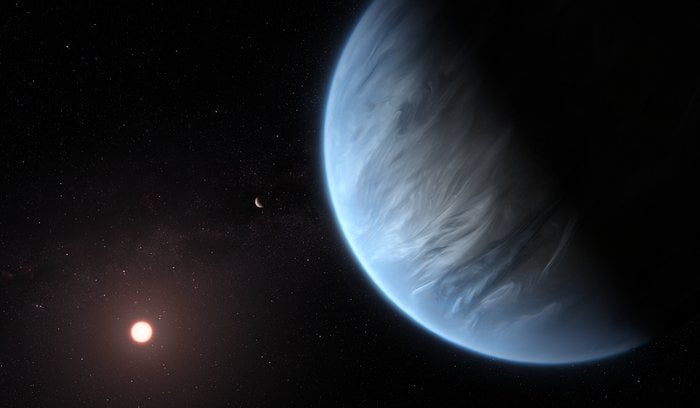

Back in 2023, during the James Webb Space Telescope’s early operational phase, it looked at a sub-Neptune planet that was about 2.6 times the size of Earth known as K2-18 b. The signal JWST found seemed exciting, as described in a paper published that year. It found what the authors thought to be preliminary evidence of dimethyl sulfide.

On Earth, dimethyl sulfide, or DMS as it’s known, is overwhelmingly produced by marine life. So the authors of the 2023 paper took that as an indication that K2-18 b had an ocean with plankton living in it, producing DMS at quantities that we were able to see from 124 light years away. The authors thought it might be a Hycean (which is a portmanteau of “Hydrogen” and “Ocean”) world capable of supporting life, so the discovery of DMS in its atmosphere seemed like further validation of that idea.

But, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. And, unfortunately for alien hunters, when other researchers looked at the evidence gathered by JWST, it didn’t seem that extraordinary. To be fair, much of the evidence they gathered was new, and was collected with the mid-infrared instrument on JWST (MIRI) rather than the near-infrared data collected by NIRSpec and used in the previous paper.

Dr. Becky discusses what we found on K2-18 b originally.The MIRI data showed that almost any hydrocarbon present in the atmosphere would create the same signal as the one the original authors claimed was made by DMS. In fact, one particular hydrocarbon (propyne) actually fit the data better than the DMS itself. So where did the original paper go wrong?

If you ask the new paper authors, they would say it’s because of Bayesian Model Comparison - a statistical trap that befalls many otherwise effective researchers. In this case, the original paper’s authors pointed out that the model including DMS fit the data better than the model containing just methane and CO2. Granted, the “data” in this case are just squiggly lines on a graph, and the JWST was being pushed to its limits observing such a small object so far away, so much of the data was undoubtedly random noise, or “artifacts” as astronomers like to call them.

Unfortunately, the authors of the first paper didn’t include models that had alternative explanations and just went with the one that included DMS, completely dismissing other possible explanations for the signal - like most other hydrocarbons, most of which have non-biological sources. This is the Bayesian Model Comparison trap - when researchers compare only binary examples to one another - i.e. does this or that model fit the data significantly better. This leads to binary outcomes, such as saying “this model is the best fit of the ones we tried”, rather than exhaustively trying all potential models that could explain the data.

Fraser discusses exoplanet atmospheres with Dr. Joanna BarstowThat is where the new paper stepped in. It looked at the fit of over 90 other models, most of which contained some form of hydrocarbon, and found that almost all of them fit the data as well or even better than the DMS did. As such, the likelihood that DMS was actually the chemical seen by JWST dropped significantly.

Such findings are a necessary part of the scientific process - they serve as part of its self-correcting mechanism. And, like good scientists, the authors have a suggestion for how this debate could be further resolved. And, like almost all astronomers, their suggestion is to build a larger telescope. In this case, the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), which will be ground-based rather than space-based, should be able to provide higher resolution images of K2-18 b that would more clearly differentiate what type of gas is in its atmosphere. If it is DMS, then great, the original authors’ claim will have been upheld and humanity might have found its first “smoking gun” of biological life outside our solar system. But, more likely, the signal is caused by some other hydrocarbon, or combination thereof, and data from the ELT can parse out which ones. Even if that is the final result, we can still rejoice in the scientific process continuing along and helping us temper our discoveries when we get too excited about them.

Learn More:

L. Welbanks et al. - Challenges in the detection of gases in exoplanet atmospheres

UT - There are Many Ways to Interpret the Atmosphere of K2-18 b

UT - More Questions About Life on Exoplanet K2-18b

UT - Another Explanation for K2-18b? A Gas-Rich Mini-Neptune with No Habitable Surface

Universe Today

Universe Today