Jupiter enters the evening sky and dominates the night.

It was a question I heard lots this past weekend. “What’s that bright star near the Full Moon?” That ‘star’ was actually a planet, as Jupiter heads towards opposition rising ‘opposite’ to the setting Sun this coming weekend. This places the King of the Planets high in the northern sky, in the same general spot the Full Moon occupies in January.

Jupiter at opposition 2026 sees the gas giant well-placed for northern hemisphere viewers, as it stays above the horizon on long winter nights from dusk until dawn. In 2026, opposition occurs on January 10th. Jupiter passes 4.23 Astronomical Units (AU)(393 million miles or 633 million kilometers) from Earth on January 8th, shining at a maximum of magnitude -2.7 and sporting a 47” disk.

Jupiter rising. Credit: Stellarium.

Jupiter rising. Credit: Stellarium.

This is one of the northernmost oppositions for Jupiter for this decade. This opposition in Gemini is also the northernmost for Jupiter until 2036, following a roughly once a decade cycle.

Last year was a ‘skip’ year for Jupiter, in terms of opposition. On an 11.9-year orbit around the Sun, oppositions for Jupiter shift about 30 degrees eastward from one to the next, as it visits the next zodiacal constellation along the ecliptic. The next skip year for the planet is in 2037.

Jupiter is the fourth brightest natural object in our Earthly skies, behind the Sun, the Moon and Venus. In fact, you can spot Jupiter in the daytime if you known exactly were to look for it. Pre- sunset after opposition is the very best time to try and accomplish this feat of visual athletics. Note Jupiter’s location the night prior to your attempt versus a landmark on the horizon such as a hilltop or a pole, then stand in the same place and watch the next evening before sunset, remembering where you saw the planet the night before. Can you tease out Jupiter with binoculars or by simple 'Mk-1 eyeball?'

Jupiter near the waning daytime Moon. Credit: Dave Dickinson.

Jupiter near the waning daytime Moon. Credit: Dave Dickinson.

A nearby Moon can help in this quest. The Moon passes 3.8 degrees north-northeast of Jupiter on the final day of this month January 31st, just a day prior to February 1st’s Full Moon.

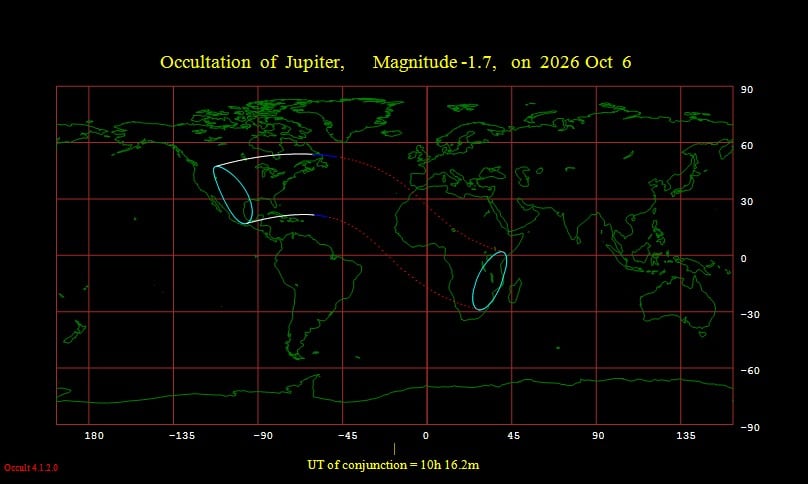

The Moon also starts a series of four occultations of Jupiter on September 8th running through November 30th of this year… the very best of which goes down very early on the morning of October 6th for eastern North America:

Occultation visibility footprint. Credit: Occult 4.2.

Occultation visibility footprint. Credit: Occult 4.2.

In the eyepiece of even a modest-sized telescope, the first thing you’ll notice looking at Jupiter are the major cloud bands. You’ll also notice its retinue of four major moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. It can be a true thrill, to watch this ‘mini-solar system’ change its configuration from one night to the next.

The moons at opposition cast their shadows almost straight back on to the cloud tops of Jove. They’ll shift to one side and reappear shortly as the planet heads towards eastern quadrature on April 5th. With some practice, you can identify a moon just by the hue and size of its shadow, from the inky pinpoint of a dot for Io, to the gray-shrouded penumbral haze of Callisto’s shadow.

The orbital plane of the moons reach edge-on around October 2026 as seen from the Earth, meaning we’ll once again start to see mutual transit season for the moons in late 2026, as one passes in front of the other.

Jupiter spins on its axis once just shy of every 10 hours, faster than any other planet in our solar system. This means that around opposition you can actually follow the cloud band features through one complete rotation in a single evening. The Great Red Spot located in the Southern Equatorial band makes a great visual anchor-point. In recent decades, the Spot has lost some of its 19th century crimson luster, and instead appears more salmon to brick hued.

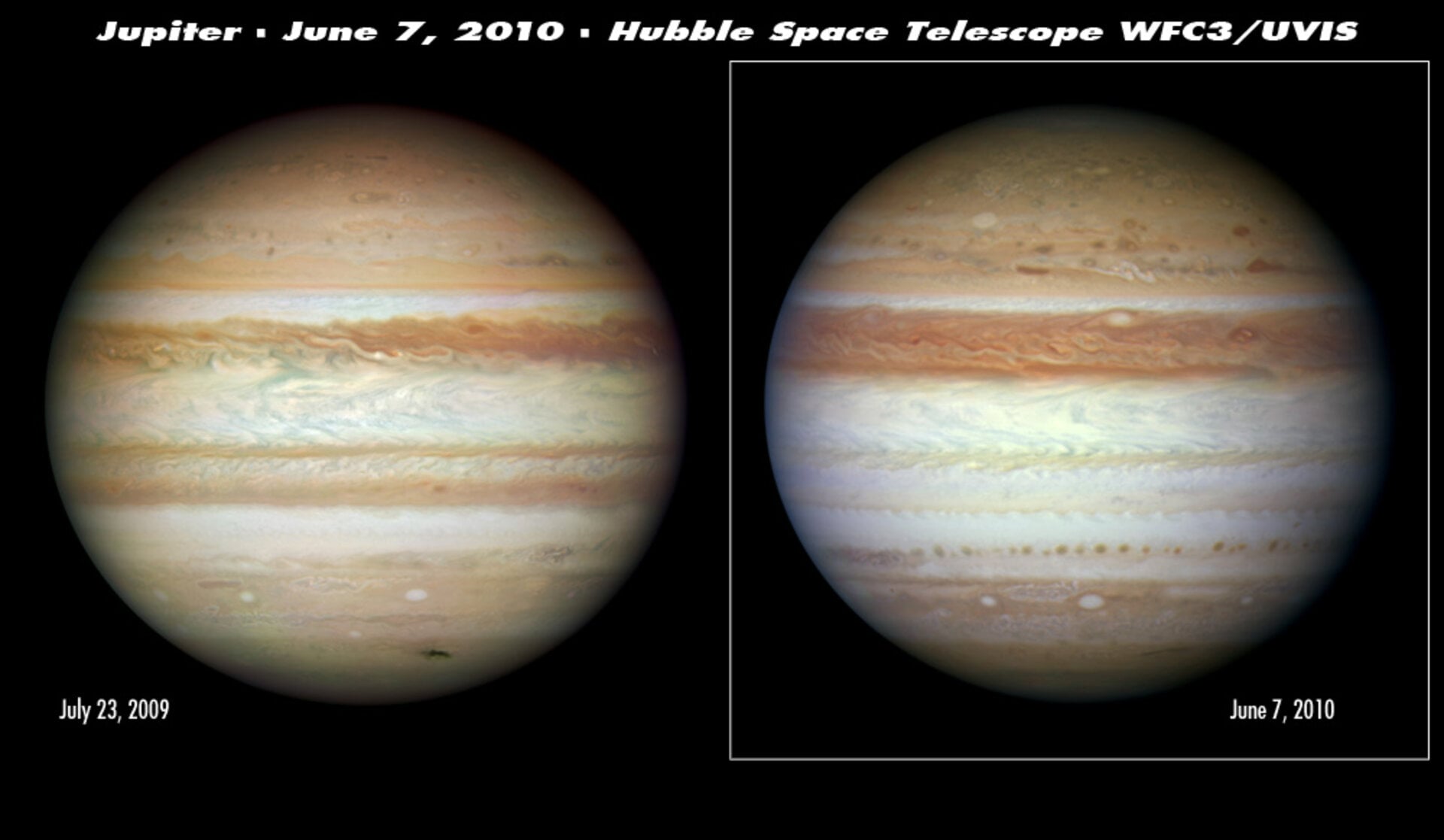

The Southern Equatorial cloud band can also on occasion pull a vanishing act, sinking from visibility. The last time it did this sort of once-a-decade disappearance was in 2010, so you could say we’re due.

The Southern Equatorial Belt pulls a vanishing act. Credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble/STScI.

The Southern Equatorial Belt pulls a vanishing act. Credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble/STScI.

Be sure to brave the cold January nights to check out the King of the Planets at its very best.

Universe Today

Universe Today