One of the primary goals of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is to detect atmospheres around exoplanets, to try to suss out whether or not they could potentially support life. But, in order to do that, scientists have to know where to look, and the exoplanet has to actually have an atmosphere. While scientists know the location of about 6000 exoplanets currently, they also believe that many of them don’t have atmospheres and that, of the ones that do, many aren’t really Earth-sized. And of those, many are around stars that are too bright for our current crop of telescopes to see their atmosphere. All those restrictions mean, ultimately, even with 6000 potential candidates, the number of Earth-sized ones that we could find an atmosphere for is relatively small. So a new paper available on arXiv from Jonathan Barrientos of Cal Tech and his co-authors that describes five new exoplanets around M-dwarf stars - two of which may have an atmosphere - is big news for astrobiologists and exoplanet hunters alike.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) discovered these five candidates, but to “confirm” them requires additional work, which is reported for the first time in this new paper. When TESS finds a potentially interesting signal, its operators release a TESS Object of Interest (TOI) alert that notifies the public about a new exoplanet candidate. Confirming a candidate usually requires follow-up observations such as transit photometry or potentially even high-resolution imaging.

Doing so for these planets was really a team effort, involving data from at least nine different telescopes, including the Keck II Observatory and the Hale Telescope. All that data served to confirm the existence of five planets in four separate systems - one system had two planets that were in resonance with one another. Four were “Super-Earths” ranging from 1.28 to 1.56 times the size of our planet, while the other one, known as TOI-5716b was right around Earth’s size.

Fraser discusses exoplanet atmospheres with Dr. Joanna BarstowOne major difference between our home planet and those found around distant stars is their orbital period. They ranged from .6 days to 11.5 days, which is obviously absurdly quick but pretty normal for most current exoplanet candidates, given the limited amount of telescope time able to be devoted to them. But perhaps more importantly, they are all located around M-dwarf stars.

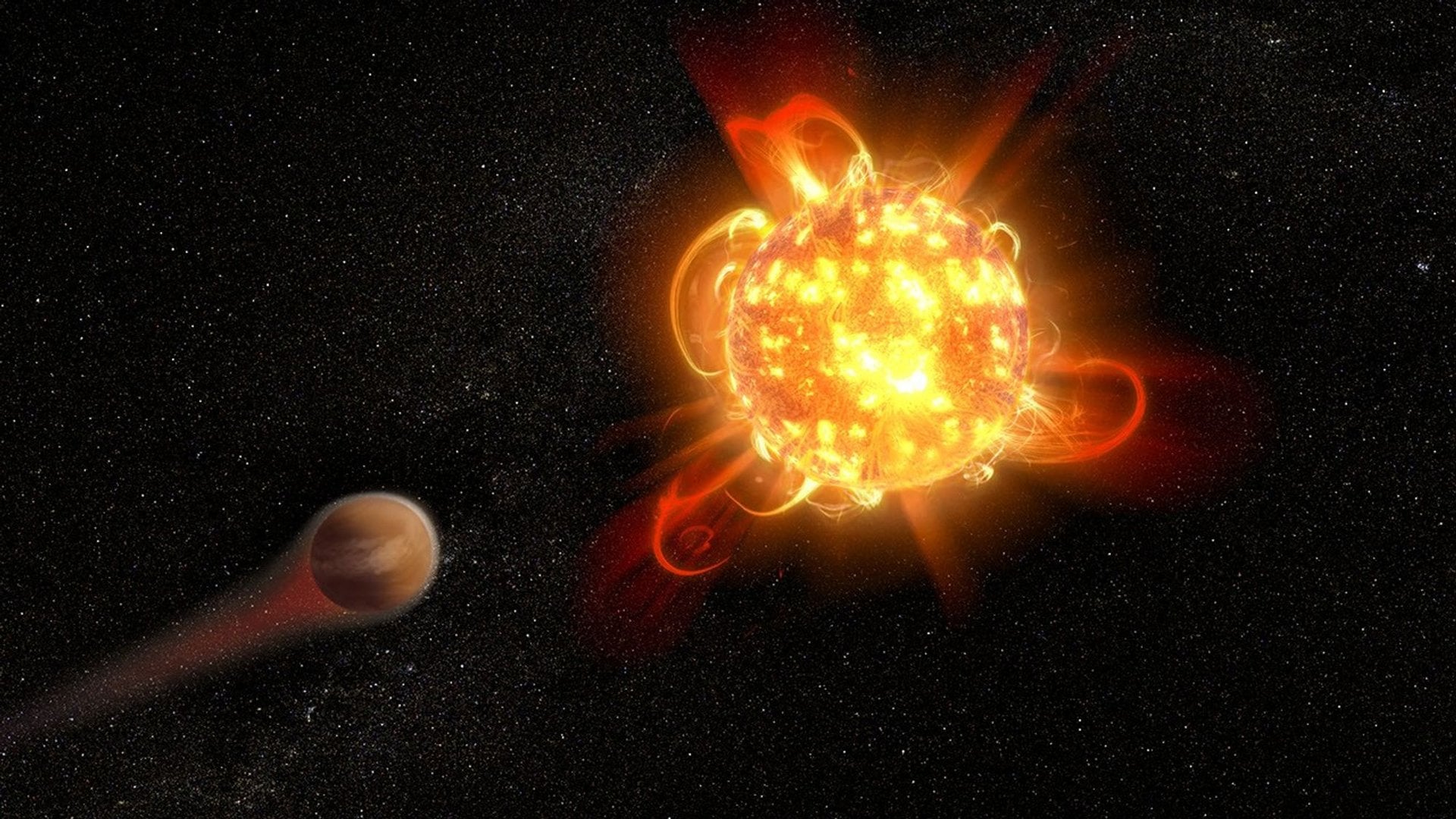

That’s important for two reasons. First, M-dwarfs are relatively dim, which means its much easier for a telescope like the James Webb Space Telescope to block out the star’s light while attempting to resolve an atmosphere. But, on the other hand, they are also notoriously volatile, with massive X-ray and ultraviolet flares that can “sandblast” away a planet’s atmosphere if they are too close to the star.

Scientists account for this sandblasting effect by estimating a “cosmic shoreline”. It represents a plot between the “insolation” (i.e. sunlight/radiation) a planet receives and its gravity. Higher insolation blows atmospheres off planets more readily. But higher masses allow a planet to keep a stronger grip on its atmosphere. This plot of insolation vs gravity draw a very clear, linear line, which scientists have taken to calling the cosmic shoreline.

Fraser discusses the technology we'll need to observe truly Earth-like exoplanets.In the paper, the five planets are actually split up into three categories. Three of the planets are very clearly “above” the cosmic shoreline, meaning the energy from their stars has likely blasted away whatever atmospheres they may have had. A fourth planet, TOI-5736b, which is the one with the shortest period, is in a category by itself since, while it receives a ton of radiation, its large radius and mass mean it could, at least theoretically, hold onto a volatile-rich (i.e. heavy) atmosphere simply because it is so large.

That leaves one stand-out - exoplanet TOI-5728b. Despite orbiting an active M-dwarf star, the atmosphere in this exoplanet seems to be enough to hold on to its atmosphere. Combining that with the fact that M-dwarfs are very dim make this planet an excellent candidate for follow-up from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to attempt a direct atmospheric detection.

Realistically, though, with a 11.5 day orbital period, the likelihood that there is any complex life on this newly confirmed planet is slim. But some extremeophiles could potentially eek out an existence if properly protected. We won’t know until we look, and this pipeline of TOI discovery to confirmation and characterization, to eventual observation by some of the most sought-after observatories in the world, is exactly how science is supposed to work.

It might be awhile before JWST, which is obviously very busy, is able to turn its attention to this one particular planet. Eventually though, we should get some data on its atmosphere, which will excite both planetary scientists and astrobiologists. They’ll just have to wait a little bit longer as the wheels of science continue to turn.

Learn More:

J. G. Barrientos et al - From Earths to Super-Earths: Five New Small Planets Transiting M Dwarf Stars

UT - Warm Exo-Titans as a Test of Planetary Atmospheric Diversity

UT - GJ 12 b: Earth-Sized Planet Orbiting a Quiet M Dwarf Star

UT - Scientists Find the Strongest Evidence Yet of an Atmosphere on a Molten Rocky Exoplanet

Universe Today

Universe Today