Since it commenced science operations in mid-2022, the James Webb Space Telescope has made significant strides in detecting atmospheres around exoplanets. These included providing the first clear evidence of carbon dioxide in an exoplanet atmosphere (WASP-39b), atmospheric water vapor (WASP-96 b), and even heavier elements like oxygen and carbon (HD149026b). According to the latest release, researchers announced that they have detected the strongest evidence to date for an atmosphere around a rocky planet.

The planet is the ultra-hot super-Earth TOI-561 b, a rocky planet 1.4 times Earth's radius that orbits a Sun-like star located about 275 light-years from Earth. With an orbital period of less than 11 hours, this planet is part of a rare class of objects known as ultra-short period (USP) exoplanets. Observations with Webb's Near-Infrared Spectrometer (NIRSpec) suggest that this planet is covered by a global magma ocean, with a thick blanket of gases above it. According to the team, these results challenge the prevailing theory that small planets that orbit close to their stars cannot maintain atmospheres.

The research was led by Johanna Teske and her colleagues from the Earth and Planets Laboratory at the Carnegie Institution for Science. They were joined by researchers from the Waterloo Centre for Astrophysics and Department of Physics and Astronomy, the Trottier Institute of Exoplanet Science, the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, the Atmospheric, Oceanic, and Planetary Physics research group at Oxford, and multiple universities. Their results were published on Dec. 11th in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

An artist’s concept shows what a thick atmosphere above a vast magma ocean on exoplanet TOI-561 b could look like. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI)

An artist’s concept shows what a thick atmosphere above a vast magma ocean on exoplanet TOI-561 b could look like. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI)

Because TOI-561 b orbits so close to its star, less than one-fortieth the distance between Mercury and the Sun, the research team concludes that it must be tidally locked, with one side permanently facing its sun. This means that dayside temperatures exceed the melting temperature of rock, creating a magma surface. What's more, measurements of the planet's size and mass revealed a surprisingly low density, a possible explanation for which is that the planet may have a relatively small iron core and a mantle composed of rock less dense than Earth's. As Teske explained in a NASA press release:

TOI-561 b is distinct among ultra-short period planets in that it orbits a very old (twice as old as the Sun), iron-poor star in a region of the Milky Way known as the thick disk. It must have formed in a very different chemical environment from the planets in our own solar system.” The planet's composition could be representative of planets that formed when the universe was relatively young.

Given its theoretical composition and the age of its parent star, roughly 10.5 billion years old, TOI-561 b could be representative of planets that formed when the Universe was relatively young. Another possibility is that TOI-561 b has an atmosphere that makes it appear larger than it is, similar to what has been observed with "super-puff" gas giants orbiting close to their stars. To test this theory, the team used Webb’s NIRSpec to measure the planet’s dayside temperature, which involved observing the system for more than 37 hours while TOI-561 b completed nearly four full orbits of the star.

During these orbits, the team measured the decrease in the system's brightness as the planet passed behind its parent star. This is essentially the reverse of what exoplanet researchers do with the Transit Method, where dips in a star's luminosity are used to detect potential exoplanets and measure their orbital period. This technique is also similar to the one used to search for atmospheres on rocky planets orbiting red dwarf stars (such as TRAPPIST-1). If no atmosphere existed, the planet would have no means of transferring heat between the dayside and nightside. In that case, the research team anticipated a dayside temperature of about 2,700 °C (4,900 °F).

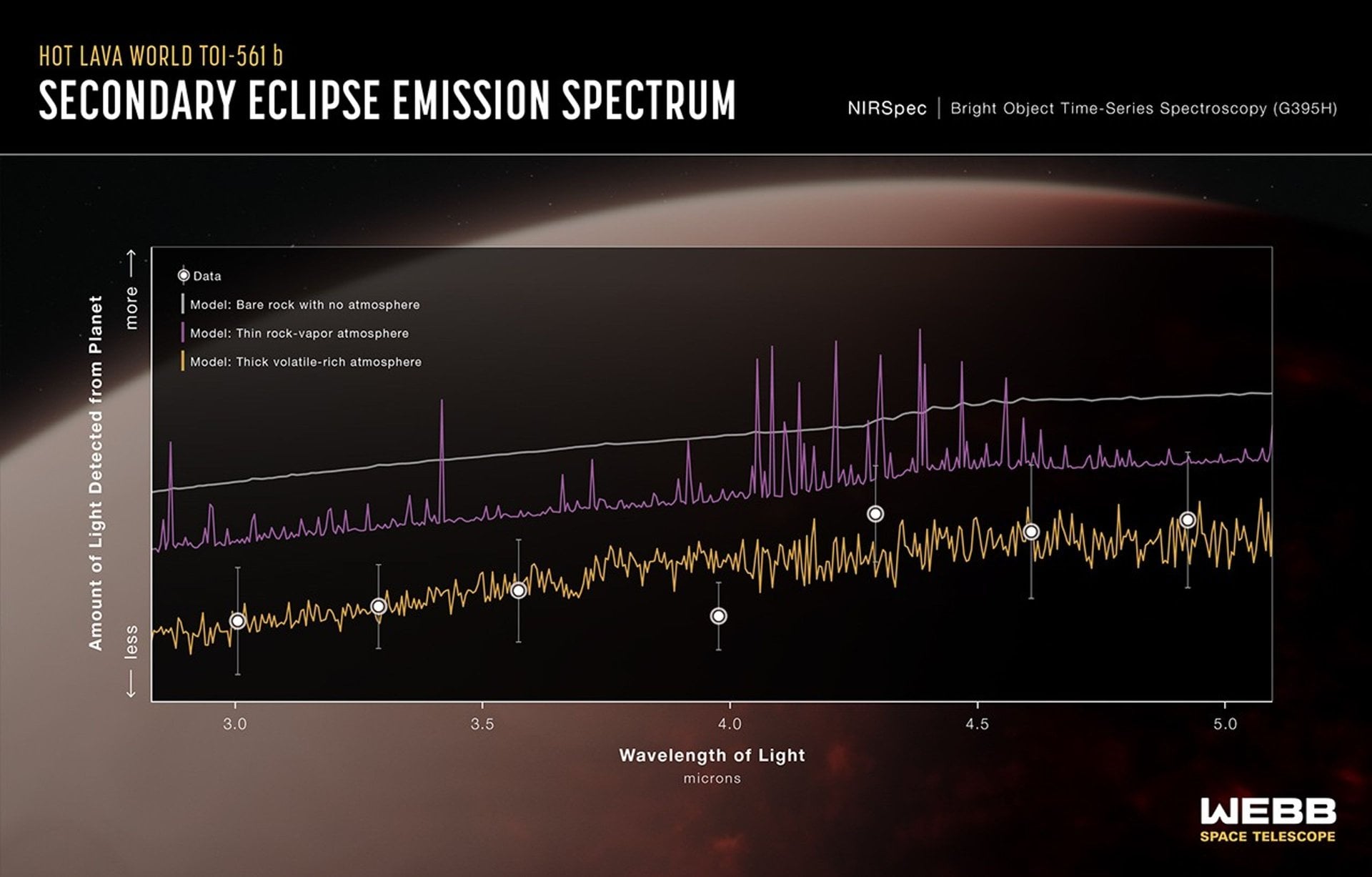

An emission spectrum captured by NASA's James Webb Space Telescope in May 2024 shows the brightness of different wavelengths of near-infrared light emitted by exoplanet TOI-561 b. Credit: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI/Teske et al. (2025).

An emission spectrum captured by NASA's James Webb Space Telescope in May 2024 shows the brightness of different wavelengths of near-infrared light emitted by exoplanet TOI-561 b. Credit: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI/Teske et al. (2025).

However, NIRSpec observations showed a dayside temperature closer to 1,800 °C (3,200 °F). Said co-author Dr Anjali Piette, from the University of Birmingham:

We really need a thick, volatile-rich atmosphere to explain all the observations. Strong winds would cool the dayside by transporting heat over to the nightside. Gases like water vapour would absorb some wavelengths of near-infrared light emitted by the surface before they make it all the way up through the atmosphere. The planet would look colder because the telescope detects less light, but it's also possible that there are bright silicate clouds that cool the atmosphere by reflecting starlight.

The question remains: how could a small, tidally-locked planet exposed to so much radiation hold onto its atmosphere, especially one as dense as TOI-561 b's appears to be. "We think there is an equilibrium between the magma ocean and the atmosphere. While gases are coming out of the planet to feed the atmosphere, the magma ocean is sucking them back into the interior," said co-author Tim Lichtenberg from the University of Groningen. "This planet must be much, much more volatile-rich than Earth to explain the observations. It's really like a wet lava ball."

These results are the first to come from Webb’s General Observers (GO) Program 3860, part of its Cycle 2 programs. The team is currently analyzing the full data set to determine temperatures on both sides of the planet and learn more about the atmosphere's composition.

Further Reading: NASA

Universe Today

Universe Today