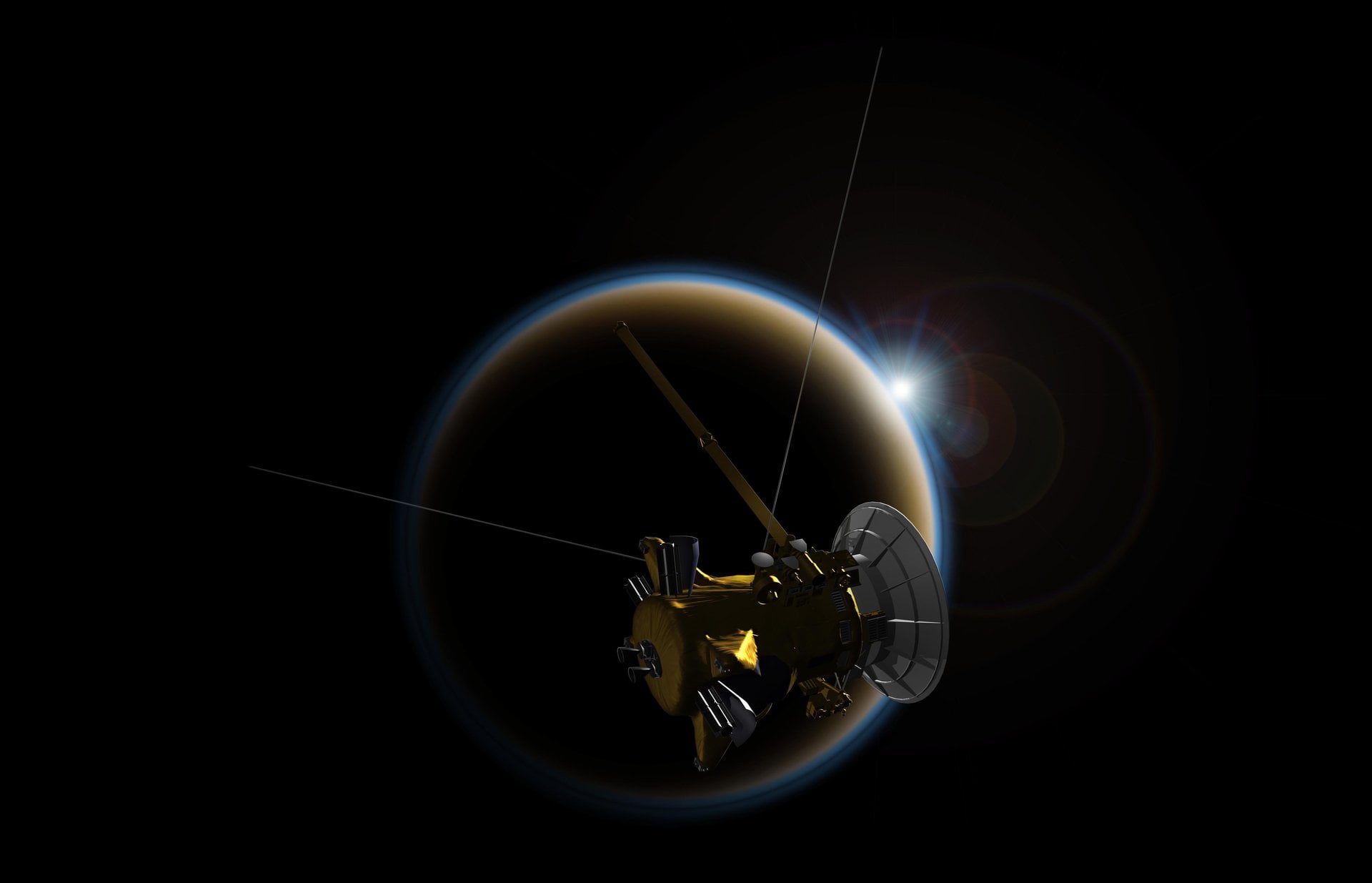

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, may not have a subsurface ocean after all.

That’s according to a re-examination of data captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which flew by Titan dozens of times starting in 2004. By 2008, all the evidence suggested a subsurface ocean of liquid water lay waiting beneath Titan’s geologically complex crust. But the latest analysis says the interior is more likely to be made of ice and slush, albeit with pockets of warm water that cycle from core to surface.

This conclusion rewrites the geologic story of one of the Solar System’s most intriguing worlds, and it was reached using only pre-existing data.

“This research underscores the power of archival planetary science data. It is important to remember that the data these amazing spacecraft collect lives on so discoveries can be made years, or even decades, later as analysis techniques get more sophisticated,” said Julie Castillo-Rogez of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in a press release. “It’s the gift that keeps giving.”

Back in 2008, the evidence for a subsurface ocean came from measurements of tidal flexing. As Titan orbits Saturn, the gas giant tugs on it (the same way our Moon tugs on Earth), stretching and squeezing the planet, distorting its shape and therefore its gravitational field. Cassini was able to ‘feel’ these perturbations during flybys. The gravitational changes affected the spacecraft’s speed, and scientists could quantify this by measuring the doppler shift of radio signals between Cassini and Earth.

Back then, the consensus was that the tidal effects were so strong that the heat produced by it must maintain an interior liquid ocean – and that liquid ocean in turn enabled more flexing than a solid icy interior could.

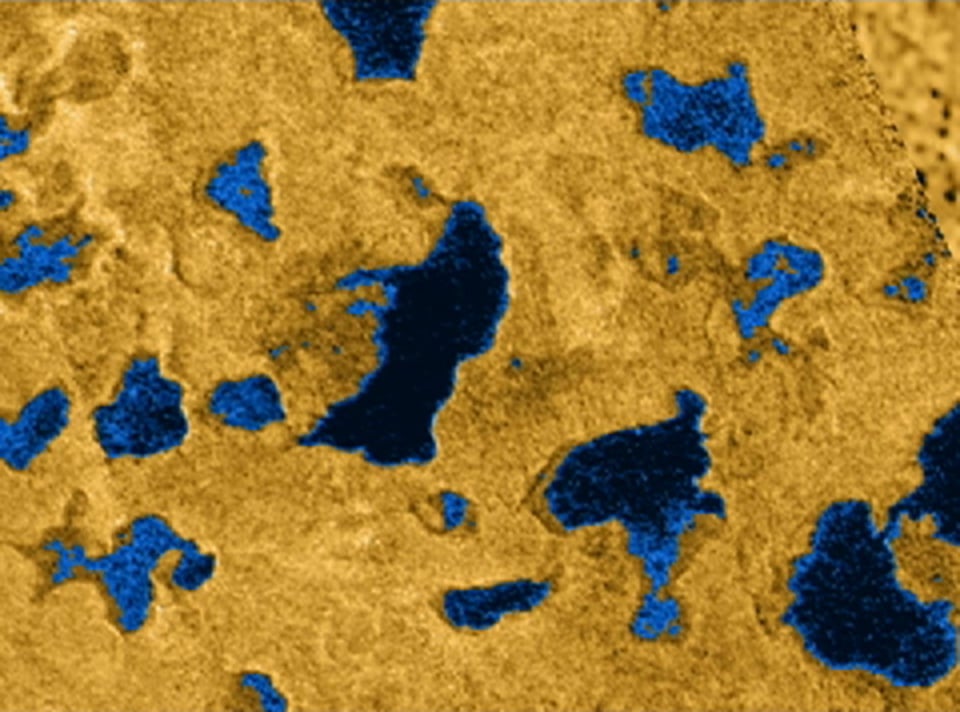

*Mosaic image of Titan's polar methane lakes, from Cassini radar data. NASA / JPL-Caltech / Italian Space Agency*

*Mosaic image of Titan's polar methane lakes, from Cassini radar data. NASA / JPL-Caltech / Italian Space Agency*

In the new analysis, published December 17, 2025, an alternative explanation for Titan’s flexibility comes in the form of a slushy mix of ice and water, rather than just water. In this scenario, researchers would expect to see greater energy dissipation in the moon’s gravitational field, and that is exactly what was found when JPL researchers used a new technique to remove noise from Cassini’s doppler data. The slush would still allow the moon to flex, but it would also remove some of the heat, thus avoiding melting into a fully liquid ocean.

For scientists interested in finding signs of organic life on Titan, the new result isn’t necessarily a disaster. In fact, it suggests a cycle in which pockets of warm water near the rocky core cycle to the surface, bringing with it vital minerals to the hydrocarbon rich crust.

“While Titan may not possess a global ocean, that doesn’t preclude its potential for harboring basic life forms, assuming life could form on Titan. In fact, I think it makes Titan more interesting,” said JPL postdoc Flavio Petricca. “Our analysis shows there should be pockets of liquid water, possibly as warm as 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit), cycling nutrients from the moon’s rocky core through slushy layers of high-pressure ice to a solid icy shell at the surface.”

Titan is likely to remain in the spotlight for the foreseeable future. Its thick atmosphere and vast surface lakes of liquid methane make it one of the most extraordinary bodies in our solar system. An upcoming NASA rotorcraft mission, Dragonfly, is expected to launch to Titan around 2028.

Read the paper: Flavio Petricca et al. “Titan’s strong tidal dissipation precludes a subsurface ocean.” Nature 2025.

Universe Today

Universe Today