New Space is a term now commonly used around the rocketry and satellite industries to indicate a new, speed focused model of development that takes its cue from the Silicon Valley mindset of “move fast and (hopefully don’t) break things.” Given that several of the founders of rocketry and satellite companies have a Silicon Valley background, that probably shouldn’t be a surprise, but the mindset has resulted in an exponential growth in the number of satellites in orbit, and also an exponential decrease in the cost of getting them to orbit. A new paper, recently published in pre-print form in arXiv from researchers at Schmidt Sciences and a variety of research institutes, lays out plans for the Lazuli Space Observatory, which hopes to apply that same mindset to flagship-level space observatory missions.

If you’ve never heard of Schmidt Sciences, you’re not alone. It is a philanthropic vehicle for Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, and his wife Wendy. They are the ones footing the bill for this $500M experiment in privately funded space telescopes.

The logic behind the project is simple - taxpayer funded observatories, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, have to utilize “flight proven” or completely derisked technology, which results in eye-watering price tags. JWST itself cost $10B when all was said and done, and Roman is currently on track to rack up $3B in expenses. These costs help ensure all the systems work flawlessly, and hopefully ensure tax payers won’t have to watch billions of dollars of their tax money go up in a fireball.

Fraser discusses the future of space telescopes.Luckily for Mr. Schmidt, even if Lazuli does end up in a fireball, he can cry into his remaining $36B fortune for comfort. In fact, that’s part of the point of the mission - it's an experiment to prove that the “move fast and break things” philosophy even works for expensive, “flagship” level space observatories. To keep the cost low, up to 80% of the telescope will use off-the-shelf components. Operating under the umbrella of Schmidt Sciences also alleviates a lot of the bureaucratic and political decision-making process that inevitably delays government-funded programs.

So where does the Lazuli fit within the wider context of space observatories? JWST is already up and operational, sending back spectacular images to Earth and seemingly producing a new academic paper every week or so. Roman is the next major one for launch, with a current scheduled date of May 2027. However, both have weaknesses when tracking “transient” phenomena, such as kilonovae or gravitational wave producing black hole mergers. These events have a time scale of hours, rather than days, and require almost immediate reaction from as many observatories as possible to catch them.

JWST, quite simply, can’t move fast enough. While it is capable of capturing extremely high resolution images of its target, it can’t rotate (or “slew” as it’s called in space telescope language) fast enough to get in position to watch these events before they end. Roman, on the other hand, is a survey telescope. It concentrates on wide swaths of the sky at any given time, but it doesn’t have the ability to resolve individual star systems or galaxies to the extent that Lazuli will.

NASA talks about the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) that will serve as one of its next major “flagship” telescopes.That “Target of Opportunity” tracking is Lazuli’s sweet spot. It will be designed to slew as quickly as possible (hopefully within an hour and a half) to a new target to observe as much data as it can of short-lived events like those that cause gravitational waves. To do so, it will have to work in concert with other, ground-based observatories like LIGO, the gravitational wave detector. But it will have the added advantage of being in space, without having to worry about cloud cover or daylight blocking its view of the critical early stages of these events.

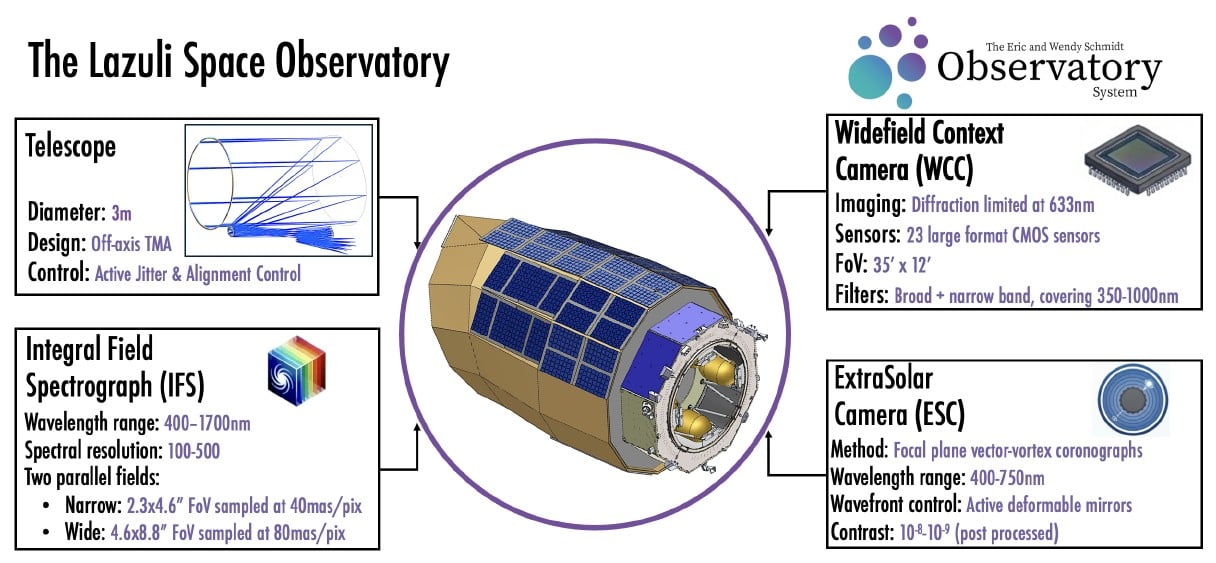

Another way Lazuli will capture transients is through its Widefield Context Camera, which, like Roman, will look at a large swatch of sky using 23 separate CMOS sensors. This will provide additional context to the other instruments on board, but can also detect small changes in stars brightness that represent exoplanet transits. In theory, at least, Lazuli should be able to detect Earth-sized planets around relatively nearby Sun-like stars.

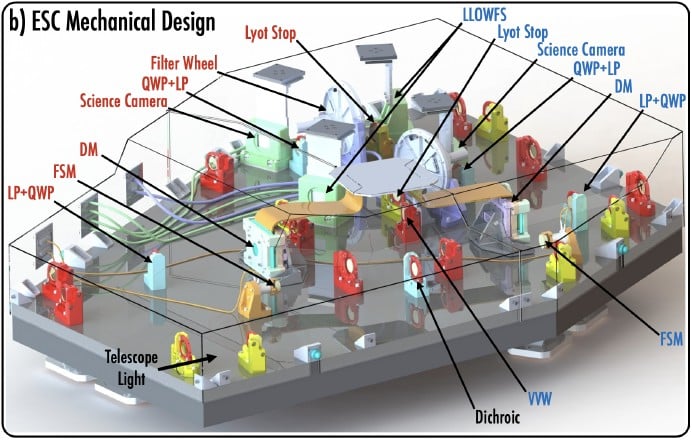

But not only will it be able to detect those exoplanets, it should also be able to directly image them. It will use a technology called a Vector Vortex Coronagraph (VVC), along with a series of deformable mirrors, to suppress starlight of individual systems by up to 10 million times. A VVC is planned for use on NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory, which is still decades away from launch, so Lazuli will even be able to serve as a technology demonstration platform for that idea well before it's put into practice in a taxpayer-funded mission.

Mechanical design of the Extra Solar Camera instrument planned for implementation on the Lazuli Observatory. Credit - A. Roy et al.

Mechanical design of the Extra Solar Camera instrument planned for implementation on the Lazuli Observatory. Credit - A. Roy et al.

Perhaps the most impressive part of this idea is that the whole mission is planned to be conceived, defined, built, and launched in a little over three years. Currently, at least, Schmidt Sciences is planning a 3-5 year development cycle for this massive space observatory - a timeline that would be exponentially faster than any comparable system developed by a government-led space organization. Given that it will be bigger than Hubble, that would be an absolutely astonishing timeline. Though, admittedly, New Space leaders have a penchant for massively underestimating the amount of time it will take to do something.

Even if it takes double that amount of time, it will still mean the world will get another flagship-level space observatory in the next decades. Or it will get an $500M lesson in what could go wrong applying speed to large-scale astrophysics projects. Luckily for Mr. Schmidt, if he just leaves his remaining $36B in an S&P index fund, he would make back around 40 times what the entire project cost him over the five-year development period, so, while he might be disappointed, he certainly won’t be broke.

Learn More:

A. Roy et al. - The Lazuli Space Observatory: Architecture & Capabilities

UT - Is the Habitable Worlds Observatory a Good Idea?

UT - The Habitable Worlds Observatory Could Find More Very Massive Stars

Universe Today

Universe Today