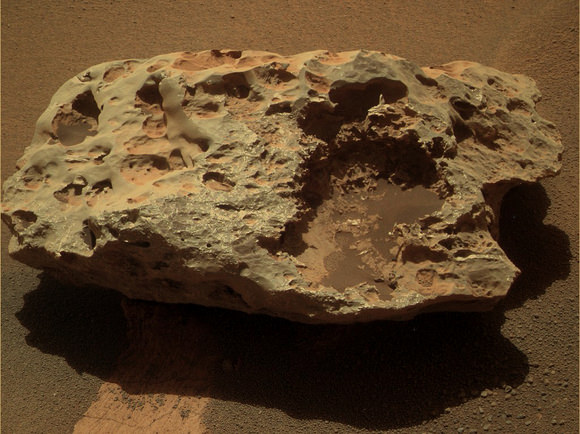

The Opportunity rover has come across an odd-shaped, large, dark rock, about 0.6 meters (2 feet) across on the surface of Mars, which may be a meteorite. The rover team spotted the rock called “Block Island,” on July 18, 2009, in the opposite direction from which it was driving. The team then had the rover do a hard right (not really, but you know what I mean) and backtrack some 250 meters (820 feet) to study it closer. Oppy has been studying the rock with its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer to get composition measurements and to confirm if indeed it is a meteorite.

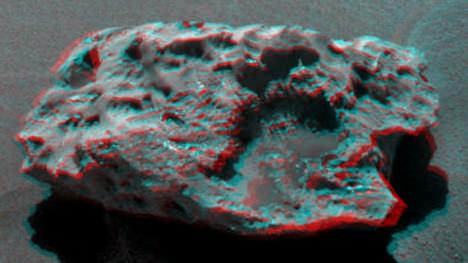

Below, see a close-up, colorized version of Block Island and a 3-D version, both created by Photoshopper Extraordinaire Stu Atkinson.

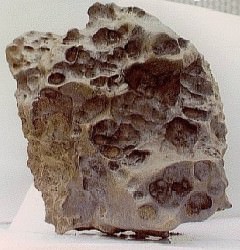

Block Island really does have a meteorite-like look to it. Stu suggested on his blog that it looks like several meteorites found on Earth, such as one of the Derrick Peak meteorites found in Antarctica, shown below. The Derrick Peak meteorites are iron meteorites, and about 27 were found in one location in Antarctica. Researchers believe they all came from one meteor shower.

Check out Stu’s blog Cumbrian Sky to see lots of other meteorites, including the one Opportunity found on Mars in 2005.

And below is a look at Block Island in 3-D. We’ll keep you posted on the results from Oppy’s examinations of this rock, and what this interesting find might tell us.

Sources: JPL, Cumbrian Sky

Shouldn’t meteorites on Mars not look like those on Earth?

If the Martian atmosphere is thinner, the rocks won’t get braked and baked as much when hurtling through it, right?

This will be the second meteor found by the rovers.. if confirmed.

There are several factors to consider Sili… Yes the atmosphere on Mars is much thinner but the meteor’s approach angle and speed would also play a role in shaping the meteorite. It is also possible that there was more then one encounter with Mars atmosphere.

@Sili

Unless of coarse when the metorites struck Mars had a thicker atmosphere. It depends maybe when it struck but it poses some interesting questions.

Cool, but what is the scientific interest of going out of their way to study meteors on mars? Can’t we study the same sorts of meteors in much more detail here on earth?

Um, if this does turn out to be a meteorite, one feels compelled to ask, where is the “impact crater”?…

@Aqua:

I’m interested to know, where was the first one, and are there images of same?

@davesmith_au: Check out the ‘Heat Shield Rock’ wiki page here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heat_Shield_Rock for pics & links. This new object sure looks like the 2005 meteorite.

Wowt hat is truly amazing dude!

RT

http://www.anon-web-tools.us.tc

Of course, the link in the article to Stu Atkinson’s blog has many great images ( some in 3-D to boot!) and a good commentary on these unusual martian meteorites. Both the wiki page and Stu note that more have been found since the 2005 discovery( some of which are shown on Stu’s blog). Per wiki: “Following the identification of Heat Shield rock as a meteorite, two additional nickel-iron meteorites were identified by the Spirit rover (unofficially named “Allan Hills” and “Zhong Shan”), and several candidate stony meteorites have been identified on Mars.”

That’s so cool!

And thanks Joe Hanford for the link, seems Meridiani Planum is an “erosion conveyor belt” for meteorites analogous to the Antarctic ones. (Though only concentrating vertically.) I still hold out hopes for seeing early Earth samples, before 3.5 Ga.

[For observing early life and its conditions. I dunno how large impacts would be required to launch samples though. Perhaps it’s a pipe dream or at least very unlikely.]

Hell, any independent samples would probably be terrific, I’m not a geologist. But perhaps geologically active Mars is the easier meteorite find location than the dead Moon.

At a guess meteorites are sufficiently rare to be worthy of study all by themselves. But I guess you would also get some idea of how these materials sort out through the solar system, their frequency, and how different environments affect them.

Quoting Hanford’s link on Heat Shield rock:

Hmm. On second thought, if Theia succeeded in launching the Moon material… The Heavy Late Bombardment ought to have packed some punches, and chances is that life existed throughout it. There’s various results hinting at that this can’t be excluded.

And at that, perhaps life even existed already during the tail of the earlier heavy one at the end of planet formation. Depending on crust formation times, obviously. That abiogenesis was sufficiently fast, on the order of ~ 10 ky, can’t be excluded either.

With one “sure” opportunity (perhaps two) for launching Earth material, it must have happened, no? I should probably dig for impact models and simulations to see what amount of ejecta I can hope for.

Steve Squyres said at the Mars Society convention that this was the fourth meteorite found by the rovers. I think the other two were found by Spirit:

http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/press/spirit/20060710a.html

@Sili: I believe that braking happens for the most part in the less dense, highest parts of the atmosphere (70-50km on Earth?), and a meteorite of that size should be sufficiently slowed down before reaching the denser, Earth-only layers, that it would not be affected anymore.

The only difference on Mars would be the altitude at which this happens.

I remember reading something about this, maybe on UT about the difficulties of slowing spacecraft for a Mars landing.

THis rock definately looks out of place. The rocks underneath to sand dune appearing waves of dust or sand appear more sedimentary.

The lower parts of Earth’s atmosphere plays a roll in braking rather massive meteoroids I don’t know the numbers, but this rock might have essentially dropped a part of the way down. It also could be a fragment of a piece of a larger meteoroid which impacted further away.

LC

It’s nice to see Opportunity continue to live up to its name!

At first glance I thought this might be a Where In The Universe challenge. A distinctive rock on a serene shoreline with little ocean wavelets cresting in the distance… and footprints… oh wait those aren’t footprints… where is this again? 🙂