[/caption]

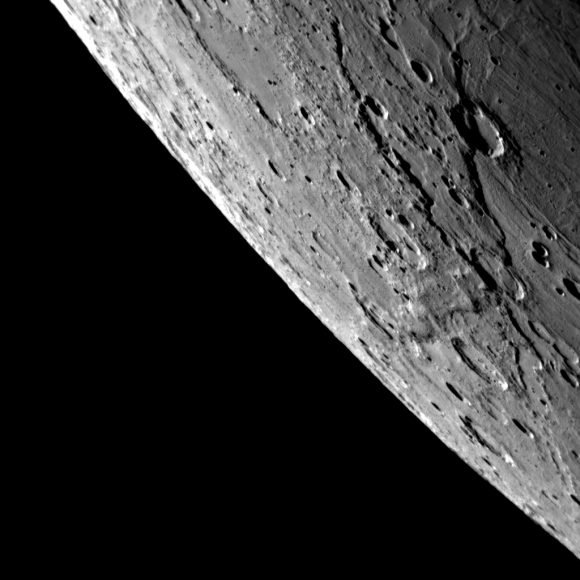

Here’s the first image from MESSENGER’s flyby of Mercury on Monday. The bright crater just south of the center of the image is Kuiper, which has been seen before on images from the Mariner 10 mission in the 1970s. But most of this image, to the east, or right of Kuiper, toward the limb of Mercury is new territory for human eyes – at least in optical views. The image was taken by the Wide Angle Camera as MESSENGER was departing from the planet, and are among the first spacecraft views of that portion of Mercury’s surface. Most striking are the large pattern of rays that extend from north to south, almost along the entire face of Mercury. Amazing! This extensive ray system appears to emanate from a relatively young crater newly imaged by MESSENGER, providing a view of the planet distinctly unique from that obtained during MESSENGER’s first flyby.

2nd Update: (9:40 am CDT) More images!

Update: (8:50 am CDT) See 2nd image released below:

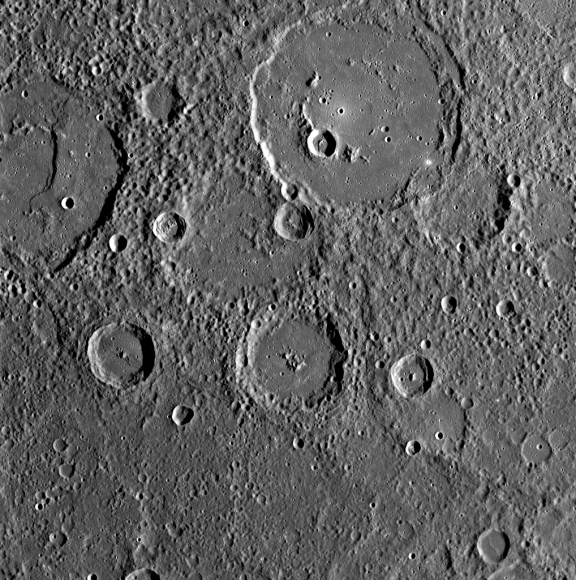

Above is the 3rd image released from the second flyby, a spectacular close-up of Mercury, as seen by the MESSENGER as it approached the planet, at about 17,100 kilometers (10,600 miles) altitude. The features in the foreground, near the right side of the image, are close to the terminator, the line between the sunlit dayside and dark night side of the planet, so shadows are long and prominent. The MESSENGER team has only had a few hours to examine these intriguing features, and, currently, more images from the flyby are still streaming back to Earth.

Here’s the second image released from the flyby. This is a close-up image taken 9 minutes and 14 seconds after MESSENGER’s closest approach to Mercury, when the spacecraft was moving at 6.1 kilometers/second (3.8 miles/second). The largest impact feature at the top of the image is about 133 kilometers (83 miles) in diameter and is named Polygnotus. This area was imaged previously by Mariner 10.

More on the first image: Data from the flyby started coming back to Earth early this morning, at about 1:50 am EDT. This spectacular image is one of the first to be returned and was taken about 90 minutes after the spacecraft’s closest approach to Mercury. This young, extensively rayed crater, along with the prominent rayed crater to the southeast of Kuiper, near the limb of the planet, were both seen in Earth-based radar images of Mercury but not previously imaged by spacecraft. As the MESSENGER team is busy examining this newly obtained view that is only a few hours old, data from the flyby continue to stream down to Earth, including higher resolution close-up images of this previously unseen terrain.

MESSENGER completed the flyby on Oct. 6 at 4:40 am EDT.

We’ll add more images as they become available.

Source: MESSENGER Gallery

I though that by being closest to the sun Mercury would be different I don’t know how different but it looks just like the moon.

That would have made a tricky “Where in the Universe”. Incredible images to be sure

Why isn’t Mercury volcanic? Venus, earth, mars are.

So Mercury has its own Tycho now.

Now people will say even more that the planet is just like the Moon.

I kinda miss the old Mariner 10 images, not entirely sure why. Maybe having only them to look at for 35 years is part of the reason.

Before Mariner 10 arrived in 1974, there were people who speculated that Mercury would be a totally flat and dull surface, having been completely melted from being so close to the Sun. Guess not.

Does it bother anyone that the “ejecta” rays are not usually straight, are not always associated with craters and do not in many cases lead to a crater, and display a fractal pattern close to craters? Impact ejecta would have to follow a ballistic trajectory emanating from the point of impact, and could only leave a straight (as projected onto a sphere, thus a geodesic) ground track. The odd morphologies I mention are highly evident in the photo, and can be seen on the moon too. For instance, between the two prominent ray craters is at least one ray that appears to be disassociated from any origin.

cool images. although the first one reminds me of a watermelon :p

“# joe Says:

October 7th, 2008 at 8:09 am

“Why isn’t Mercury volcanic? Venus, earth, mars are.”

Mercury has had extensive volcanism acting in the distant past, particularly around the Caloris Basin. The planet has cooled far too much for there to be any significant volcanism these days.

Wicked images ..

@Bill, I’m hearing you, but, being as close to the sun, and having a very thin atmosphere, maybe the ejecta gets buffeted about as it settles back down. Just throwing it out there with no basis other than guesswork, I can only imagine that solar winds would do quite a good job of moving something bright and reflective .. ?

Once the ejecta is blown out in a straight radial pattern the ballistic return imprint on the surface must account for the spin of the planet during the time of travel of this debris. I suspect a slightly spiral pattern along the north south meridian and a linear compression effect along the east west orientation. As to the lack of apparent crater for a ray maybe it belongs to a feature behind the visible limb.