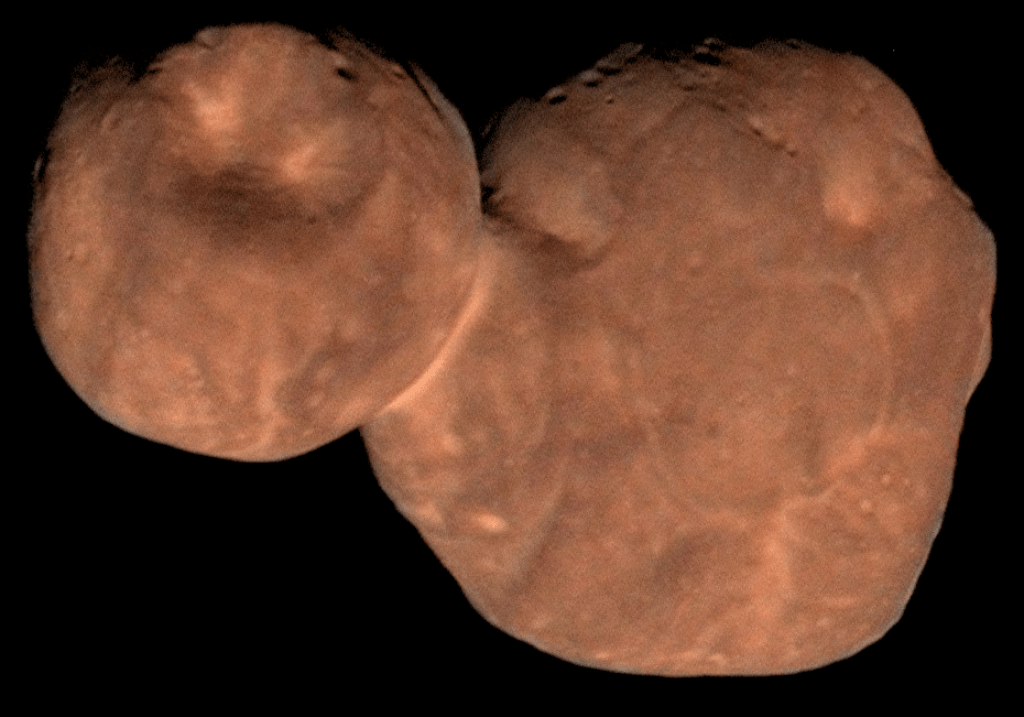

When New Horizons flew past Arrokoth in 2019, it revealed close-up images of this enigmatic Kuiper Belt Object for the first time. Astronomers are still studying all the data sent home by the spacecraft, trying to understand this two-lobed object, which looks like a red, flattened snowman.

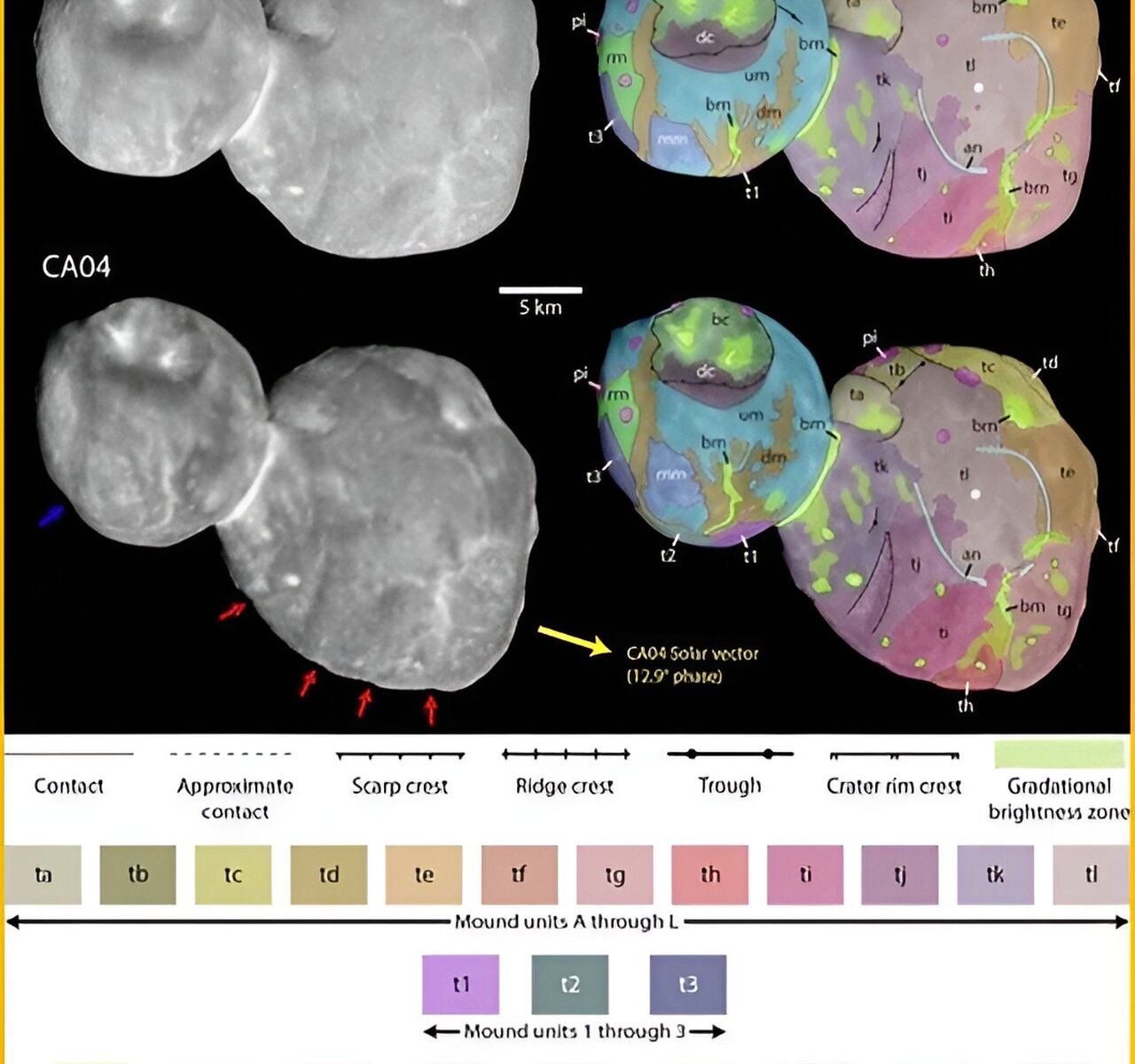

Scientists have now identified 12 mounds on Arrokoth’s larger lobe, which are roughly the same size – about 5-kilometers long – as well as the same shape, color, and reflectivity. The scientists think their similar look is because they all formed the same way, where icy material slowly accumulated on the surface of Arrokoth.

A new study published in the Planetary Science Journal suggests that these mound-shaped “building blocks” could help researchers better understand how planetesimals form. These insights will be beneficial when the Lucy spacecraft arrives in Jupiter’s Trojan Belt.

“Similarities including in sizes and other properties of Arrokoth’s mound structures suggest new insights into its formation,” said Alan Stern, the Principal Investigator of the New Horizons mission, presenting the findings this week at the American Astronomical Society’s 55th Annual Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) meeting in San Antonio. “If the mounds are indeed representative of the building blocks of ancient planetesimals like Arrokoth, then planetesimal formation models will need to explain the preferred size for these building blocks.”

Arrokoth is one of the thousands of small icy bodies in the Kuiper Belt, a massive population of objects that are essentially leftover material from the formation of the Solar System. Much like the Main Asteroid Belt, the Kuiper Belt is also home to several larger bodies, such as Pluto and Charon. Since the turn of the millennium, many more have been discovered, like Eris, Haumea, Makemake, 2007 OR10, Quaoar, and others.

Arrokoth — which had an original designation of (486958) 2014 MU69 — is the most distant and most primitive object ever explored by a spacecraft. It was discovered in 2014 by NASA’s New Horizons science team, using the Hubble Space Telescope.

New Horizons flew by Arrokoth on Jan. 1, 2019, snapping pictures showing the strangely shaped object. It wasn’t until well after the flyby that scientists realized the two lobes on Arrokoth were not round, but flattened like a pancake.

“It’s amazing to see this object so well preserved that its shape directly reveals these details of its assembly from a set of building blocks all very similar to one another,” said Lowell Observatory’s Dr. Will Grundy, co-investigator of the New Horizons mission, in a Southwest Research Institute press release. “Arrokoth almost looks like a raspberry, made of little sub-units.”

Arrokoth measures about 22 miles (35 kilometers) long. It is about 12 miles (20 kilometers) wide, by 6 miles (10 kilometers) thick. Most of the mounds were identified on Arrokoth’s larger lobe, Wenu, but three more mounds were tentatively identified on the object’s smaller lobe, Weeyo.

A three-dimensional model created from images taken by the New Horizons spacecraft shows that the larger lobe is flatter and has dimensions of approximately 14 × 12 × 4 miles (22 × 20 × 7 kilometers). The smaller lobe is more rounded and is approximately 9 × 9 × 6 miles (14 × 14 × 10 kilometers) in its dimensions.

You can see an interactive 3D version of Arrokoth here.

Credit: Courtesy of New Horizons/NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/James Tuttle Keane

Scientists say the shape of Arrokoth indicates that its two lobes most likely formed separately and gently merged within a cloud of particles early in the history of our solar system. It is thought that Arrokoth is primordial — existing since the beginning of the solar system. The two lobes are similar in color, adding evidence to this interpretation.

Arrokoth means means ““sky” in the Powhatan/Algonquian language.

Scientists think there is a good chance that some of the flyby targets for NASA’s Lucy mission to Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids and ESA’s comet interceptor will be other pristine planetesimals, which could contribute to the understanding of accretion of planetesimals elsewhere in the ancient solar system, and whether they differ from processes New Horizons found in the Kuiper Belt.

“It will be important to search for mound-like structures on the planetesimals these missions observe to see how common this phenomenon is, as a further guide to planetesimal formation theories,” Stern said.

Lucy launched on Oct 16, 2021 and will make its first encounter with the trojan asteroid (152830) Dinkinesh on November 1, 2023.