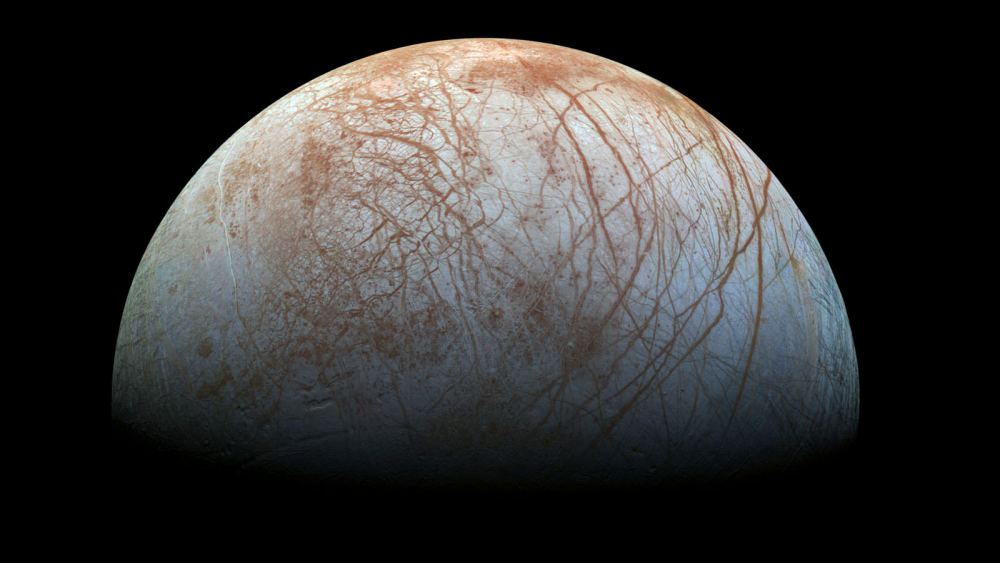

Earlier this week, we shared some stunning, newly reprocessed images of Europa from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which visited Jupiter and its moons from December 1995 to September 2003. Now, as scientists continue to revisit Galileo’s data, even more details are coming into focus about Jupiter’s enticing moon. Not only is there evidence within the past few years of geysers shooting from Europa’s surface, twenty years ago, Galileo may have also witnessed a cryovolcanic eruptions — or plumes of water — spewing from the icy moon.

Even though Galileo’s mission ended when the probe crashed into Jupiter’s atmosphere, scientists continue to revisit the treasure trove of the mission’s data. Jupiter itself is such an integral part of our Solar System, but Europa is believed to be one of the most habitable worlds in our nearby neighborhood.

Europa is covered in a thick layer of ice, which scientists strongly suspect is hiding a subsurface ocean. Steady gravitational tugs from Jupiter keep this water warm enough to be liquid, but there is plenty of evidence some of this water escapes by bursting through cracks on Europa’s icy surface. Evidence of this was first detected by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2013 and again in 2014 and 2016.

In a look back at old data, researchers have found that twenty years ago, during one of Galileo’s flybys of Europa, there was evidence – or actually a lack of evidence – of super-fast charged particles around the moon. In computer simulations that reproduced data gathered by Galileo’s onboard Energetic Particle Detector — which was specifically designed to detect such super-fast charged particles and study them — the normally abundant fast protons were disappearing during one of Europa’s flybys, flyby E26.

“What is new here is that part of the decrease can be explained by charge exchange, a process whereby the protons are removed after they lose their electrical charge in Europa’s thin atmosphere,” the team wrote in their paper. They explained that a depletion feature occurring shortly after closest approach would be associated with plume-associated field perturbations, and “we therefore conclude, with a new method and independent data set, that Galileo could have encountered a plume during E26.”

Hans Huybrighs, a research fellow at the European Space Agency and the lead author of the new study said that protons should have been recorded in abundance. But Galileo, while zipping over the moon’s northern polar regions, barely detected any. Scientists initially attributed the lack of protons to Europa itself, figuring that the moon blocked Galileo’s proton detector.

However, the new look at the old data found that some of this proton depletion was due to a plume of water vapor shooting out into space. This plume disrupted Europa’s thin, tenuous atmosphere and perturbed the magnetic fields in the region, altering the behavior and prevalence of nearby energetic protons.

Scientists have long suspected the existence of plumes at Europa and in 2018, a look at old data from Galileo’s Magnetometer (MAG) sensor showed a brief, localized bend in Jupiter’s magnetic field, which showed the cause as an interaction between the magnetic field and one of the Europa’s plumes. Then there was data from Hubble and other observatories.

Excitingly, if such plumes are indeed present and breaking through the moon’s icy shell, they would offer a possible way to access and characterize the contents of its subsurface ocean, which would otherwise be incredibly challenging to explore.

And now, there are a couple of new missions to Europa planned. ESA’s Juice mission, set for for launch in 2022, will investigate Jupiter and its icy moons. Juice will carry the equipment needed to directly sample particles within the moon’s water vapor plumes and also to detect them remotely, aiming to reveal the secrets of its vast, mysterious ocean. It is scheduled to arrive in the Jupiter system in 2029, to study the potential habitability and the underground oceans of three of the giant planet’s moons – Ganymede, Callisto and Europa.

Then, in 2023, NASA plans to launch the Europa Clipper mission, a robotic explorer dedicated to the study of Europa. It will explore Europa’s ice shell and interior to learn more about the moon’s composition, geology, and interactions between the surface and subsurface, as well as to shed light on whether or not life could exist within Europa’s interior ocean.

As this new study demonstrates, the research team said, tracing the energetic charged and neutral particles in Europa’s vicinity offers huge promise in efforts to probe the moon’s atmosphere and wider cosmic environment, which is what these upcoming missions hope to do.

Sources: ESA, Max Planck Institute