In the 1960s, astronomers began to notice that the Universe appeared to be missing some mass. Between ongoing observations of the cosmos and the the Theory of General Relativity, they determined that a great deal of the mass in the Universe had to be invisible. But even after the inclusion of this “dark matter”, astronomers could still only account for about two-thirds of all the visible (aka. baryonic) matter.

This gave rise to what astrophysicists dubbed the “missing baryon problem”. But at long last, scientists have found what may very well be the last missing normal matter in the Universe. According to a recent study by a team of international scientists, this missing matter consists of filaments of highly-ionized oxygen gas that lies in the space between galaxies.

The study, titled “Observations of the missing baryons in the warm–hot intergalactic medium“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature. The study was led by Fabrizio Nicastro, a researcher from the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF) in Rome, and included members from the SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), the Instituto de Astronomia Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, the Instituto Nacional de Astrofísica, Óptica y Electrónica, the Instituto de Astrofísica de La Plata (IALP-UNLP) and multiple universities.

For the sake of their study, the team consulted data from a series of instruments to examine the space near a quasar called 1ES 1553. Quasars are extremely massive galaxies with Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) that emit tremendous amounts of energy. This energy is the result of gas and dust being accreted onto supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the center of their galaxies, which results in the black holes emitting radiation and jets of superheated particles.

In the past, researchers believed that of the normal matter in the Universe, roughly 10% was bound up in galaxies while 60% existed in diffuse clouds of gas that fill the vast spaces between galaxies. However, this still left 30% of normal matter unaccounted for. This study, which was the culmination of a 20-year search, sought to determine if the last baryons could also be found in intergalactic space.

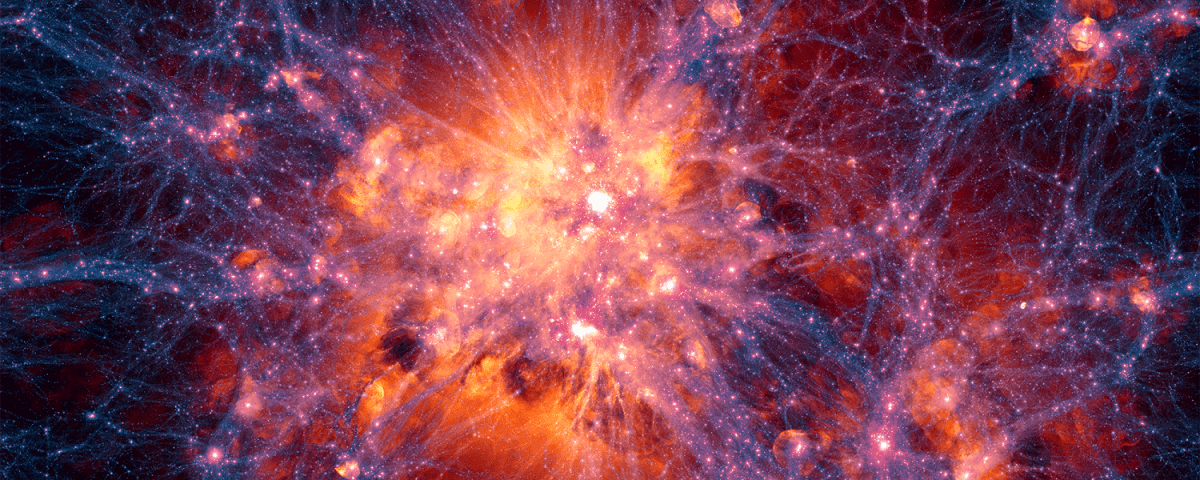

This theory was suggested by Charles Danforth, a research associate at CU Boulder and a co-author on this study, in a 2012 paper that appeared in The Astrophysical Journal – titled “The Baryon Census in a Multiphase Intergalactic Medium: 30% of the Baryons May Still be Missing“. In it, Danforth suggested that the missing baryons were likely to be found in the warm-hot intergalactic medium (WHIM), a web-like pattern in space that exists between galaxies.

As Michael Shull – a professor of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder and one of the co-authors on the study – indicated, this wild terrain seemed like the perfect place to look.“This is where nature has become very perverse,” he said. “This intergalactic medium contains filaments of gas at temperatures from a few thousand degrees to a few million degrees.”

To test this theory, the team used data from the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) on the Hubble Space Telescope to examine the WHIM near the quasar 1ES 1553. They then used the European Space Agency’s (ESA) X-ray Multi-Mirror Mission (XMM-Newton) to look closer for signs of the baryons, which appeared in the form of highly-ionized jets of oxygen gas heated to temperatures of about 1 million °C (1.8 million °F).

First, the researchers used the COS on the Hubble Space Telescope to get an idea of where they might find the missing baryons in the WHIM. Next, they homed in on those baryons using the XMM-Newton satellite. At the densities they recorded, the team concluded that when extrapolated to the entire Universe, this super-ionized oxygen gas could account for the last 30% of ordinary matter.

As Prof. Shull indicated, these results not only solve the mystery of the missing baryons but could also shed light on how the Universe began. “This is one of the key pillars of testing the Big Bang theory: figuring out the baryon census of hydrogen and helium and everything else in the periodic table,” he said.

Looking ahead, Shull indicated that the researchers hope to confirm their findings by studying more bright quasars. Shull and Danforth will also explore how the oxygen gas got to these regions of intergalactic space, though they suspect that it was blown there over the course of billions of years from galaxies and quasars. In the meantime, however, how the “missing matter” became part of the WHIM remains an open question. As Danforth asked:

“How does it get from the stars and the galaxies all the way out here into intergalactic space?. There’s some sort of ecology going on between the two regions, and the details of that are poorly understood.”

Assuming these results are correct, scientists can now move forward with models of cosmology where all the necessary “normal matter” is accounted for, which will put us a step closer to understanding how the Universe formed and evolved. Now if we could just find that elusive dark matter and dark energy, we’d have a complete picture of the Universe! Ah well, one mystery at a time…

I have been partial to the theory that these filaments pre-existed galaxy formation and served as seeds from which they formed around. Perhaps they have a dark matter core. The filaments oddly connect galaxy to galaxy which seems quite an odd coincidence if they are only a super-heated residual of quasar outbursts. These filaments also serve as attractors of intergalactic gas and serve to funnel it towards galaxies moving along them fueling their growth perhaps more then even via galactic mergers. Also galaxies moving along said filaments would seem to encourage galactic mergers which seem far more common than one would expect from random motion.

Many of us non-academic punters have not been comfortable with dark matter theories. Maybe saying “we don’t know but we need to keep looking” attracts less funding than, “here’s an explanation based on non-existions”. Bye bye WIMPs, let’s hope dark energy goes the same way soon.

I can’t calculate any physics that explains the “last atom’ theory (the last atom attracted to the gigantic/humongous/unimaginable black hole that triggered the Big Bang). Wouldn’t surprise me to find (eventually) that there are matter/energy residues more than 27/50,100,500 (who knows?) Billion years old, maybe on the other side of the universe, or right around the corner. Maybe some such residues were absorbed, and continue to absorbed by elements in our expanding universe.

I don’t think the tendrils theory works either. The density required to generate such temperatures would make them highly visible in the spectrum.