[/caption]

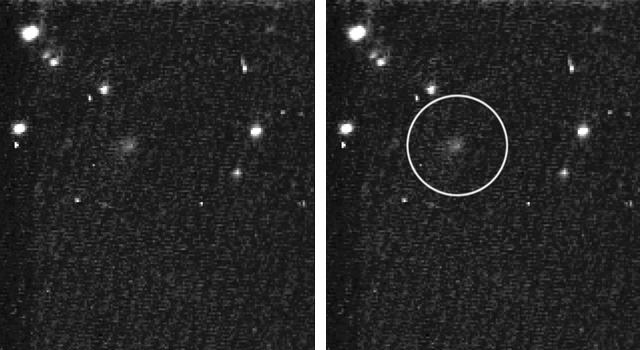

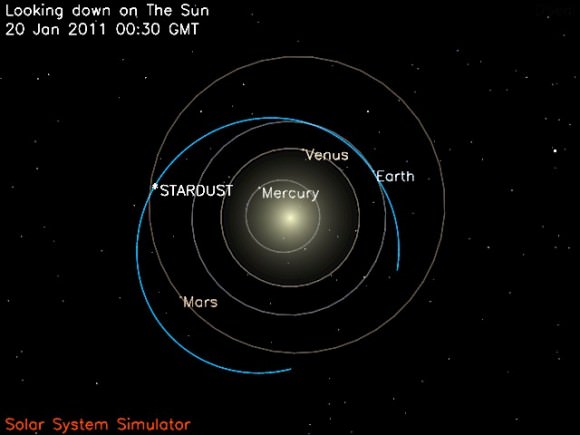

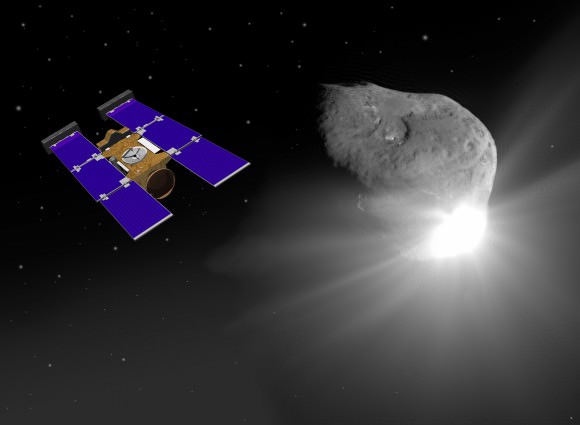

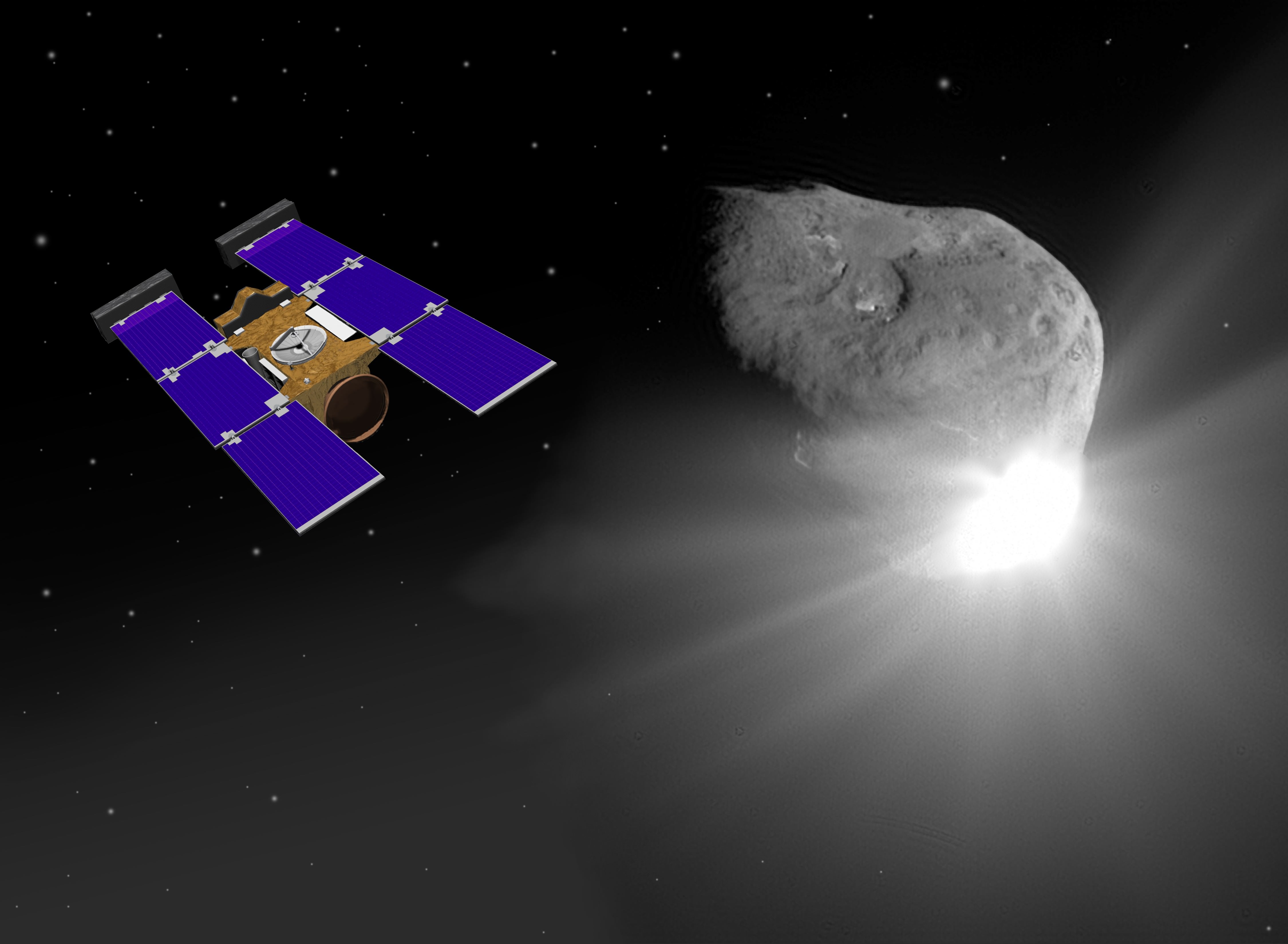

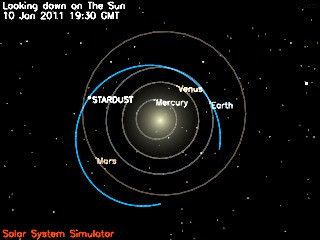

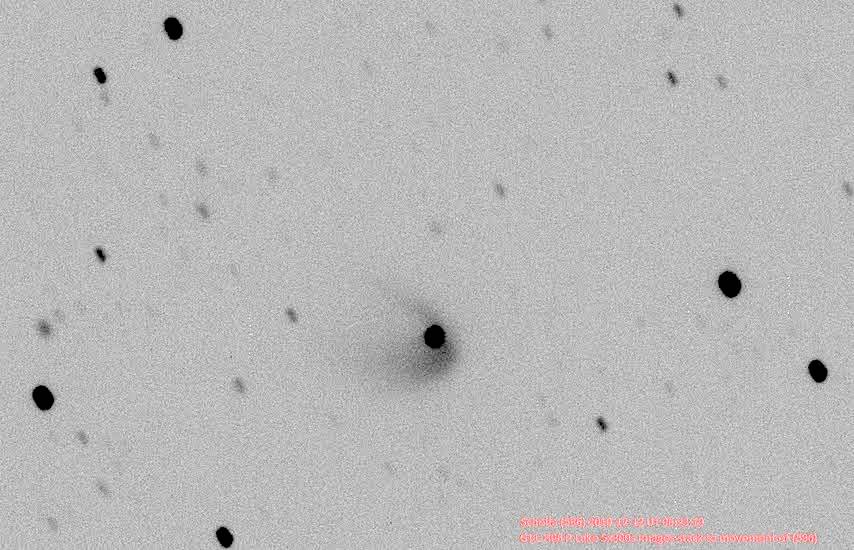

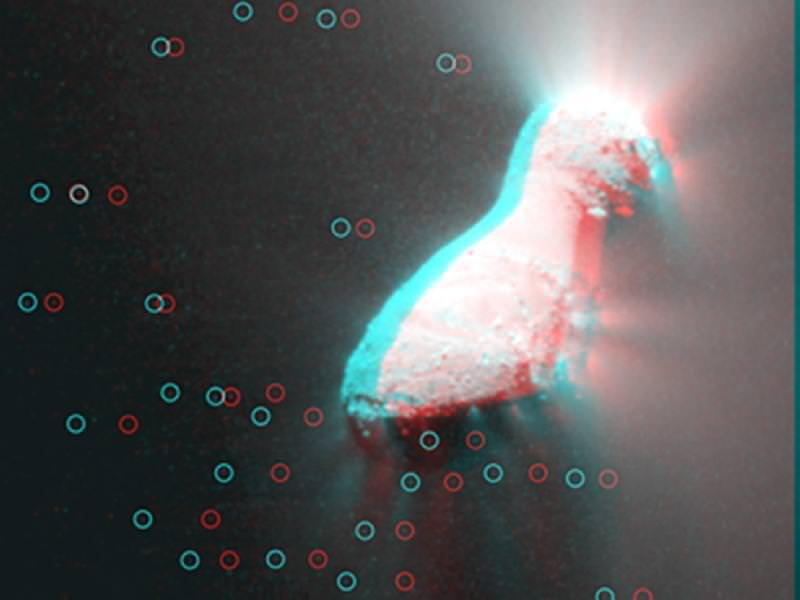

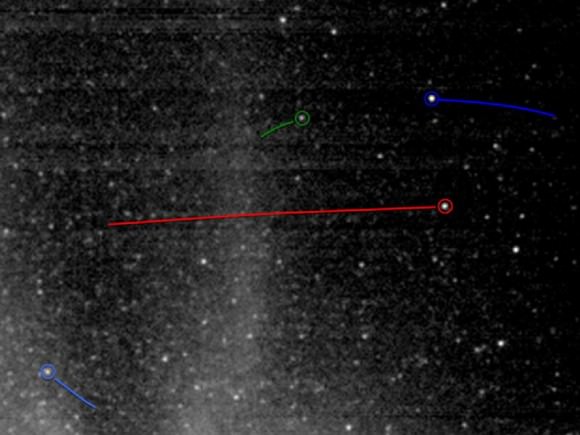

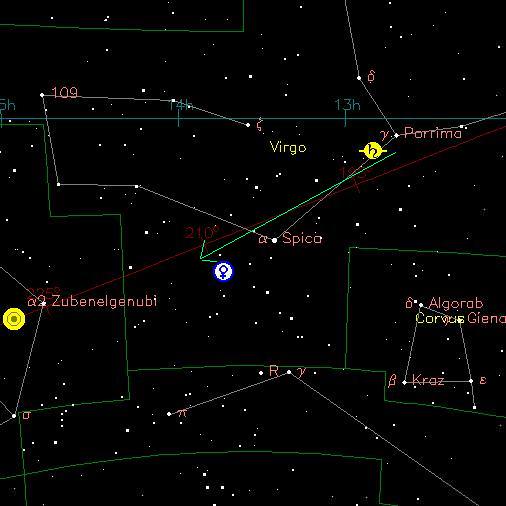

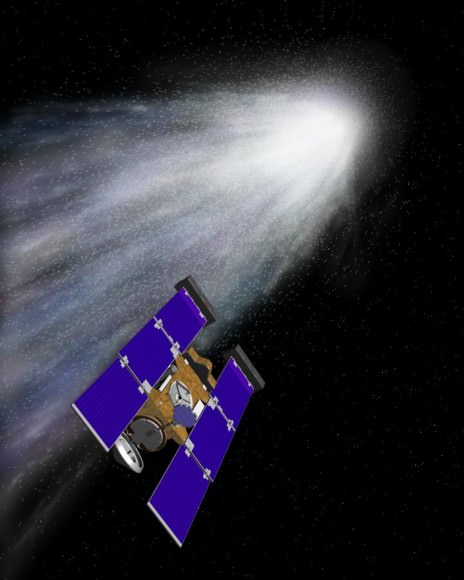

It’s comet ahoy! for the Stardust spacecraft, which is on its way to a Valentine’s Day meetup with comet Tempel 1. The images above were taken on Jan. 18 and 19 from a distance of 26.3 million kilometers (16.3 million miles), and 25.4 million kilometers (15.8 million miles). On Feb. 14, Stardust will fly within about 200 kilometers (124 miles) of the comet’s nucleus and for the first time we’ll get a second closeup look at Tempel 1.

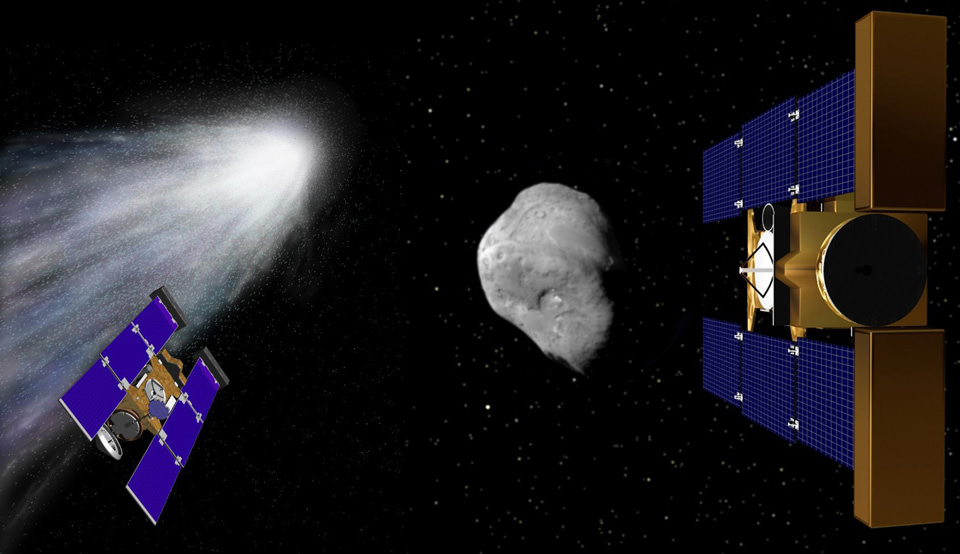

“We were there in 2005 with the Deep Impact spacecraft, said Stardust-NExT Project Manager Tim Larson, speaking on today’s 365 Days of Astronomy podcast, “and this is a golden opportunity. It’s the first time we’ve ever been able to revisit a comet on a second pass near the sun.”

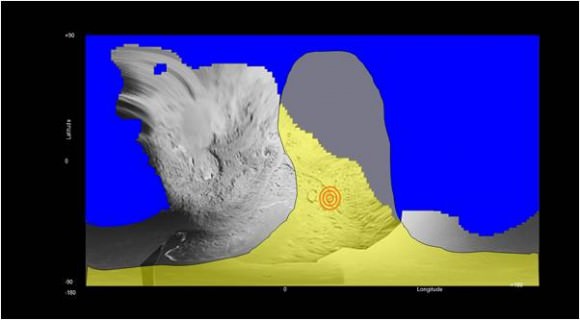

Larson said this encounter will give provide important information about how the surface of the comets change with each passage near the sun and whether the changes in the comet are global or just specific to certain areas on the surface.

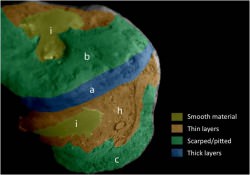

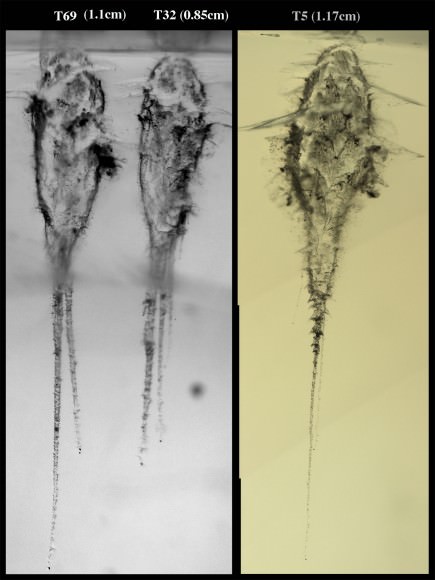

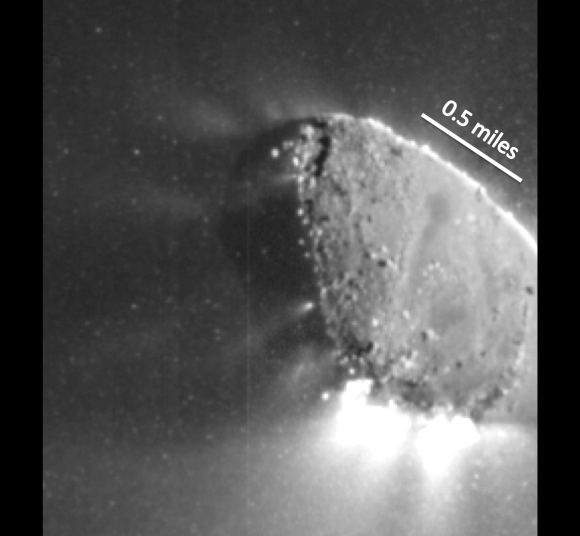

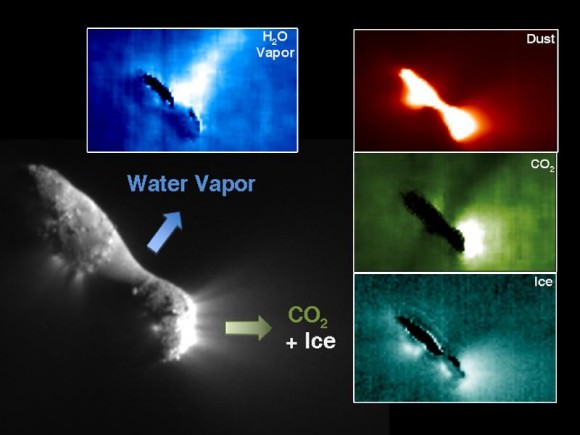

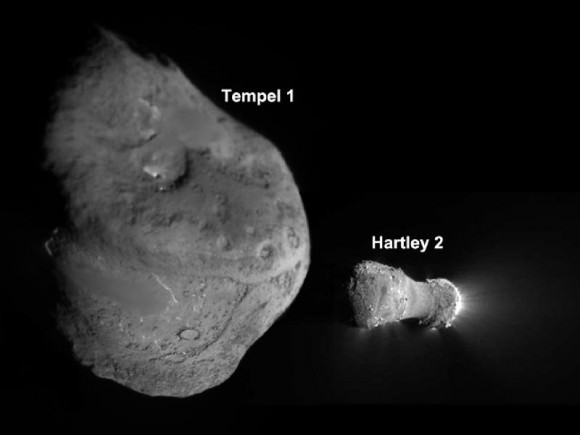

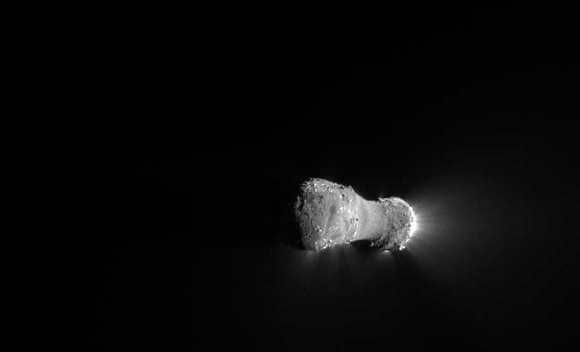

From the Deep Impact mission, we already know that comet Tempel 1 has a wide variety of features on its surface.

“We have found smooth areas that look like material flows,” Larson said,” there are rough, pitted areas, there are craters on the surface, which we don’t know if they’re impact craters or if they’re caused by material coming out from the inside of the comet. So this is a very interesting comet in terms of variety of terrain.”

The exciting part will be comparing ‘before and after’ images of Tempel 1.

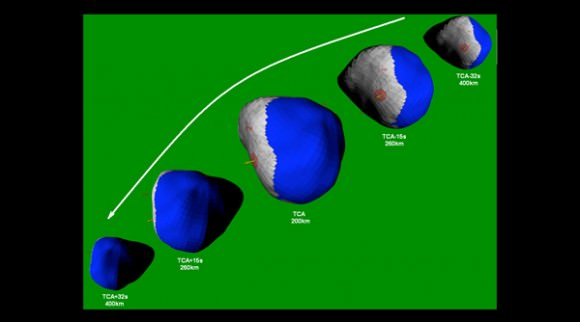

The spacecraft will be able to take up to 72 images and store them on board. Larson said the images will be carefully timed to center them around the closest approach to the comet, providing the best possible resolution.

“We should be able to get around three dozen images that are at better than 80 meters per pixel resolution and our closest approach images should be down below 20 meters per pixel resolution,” he said. “That will be good enough to resolve a lot of the key features on the surface of the comet and start that process of comparison.”

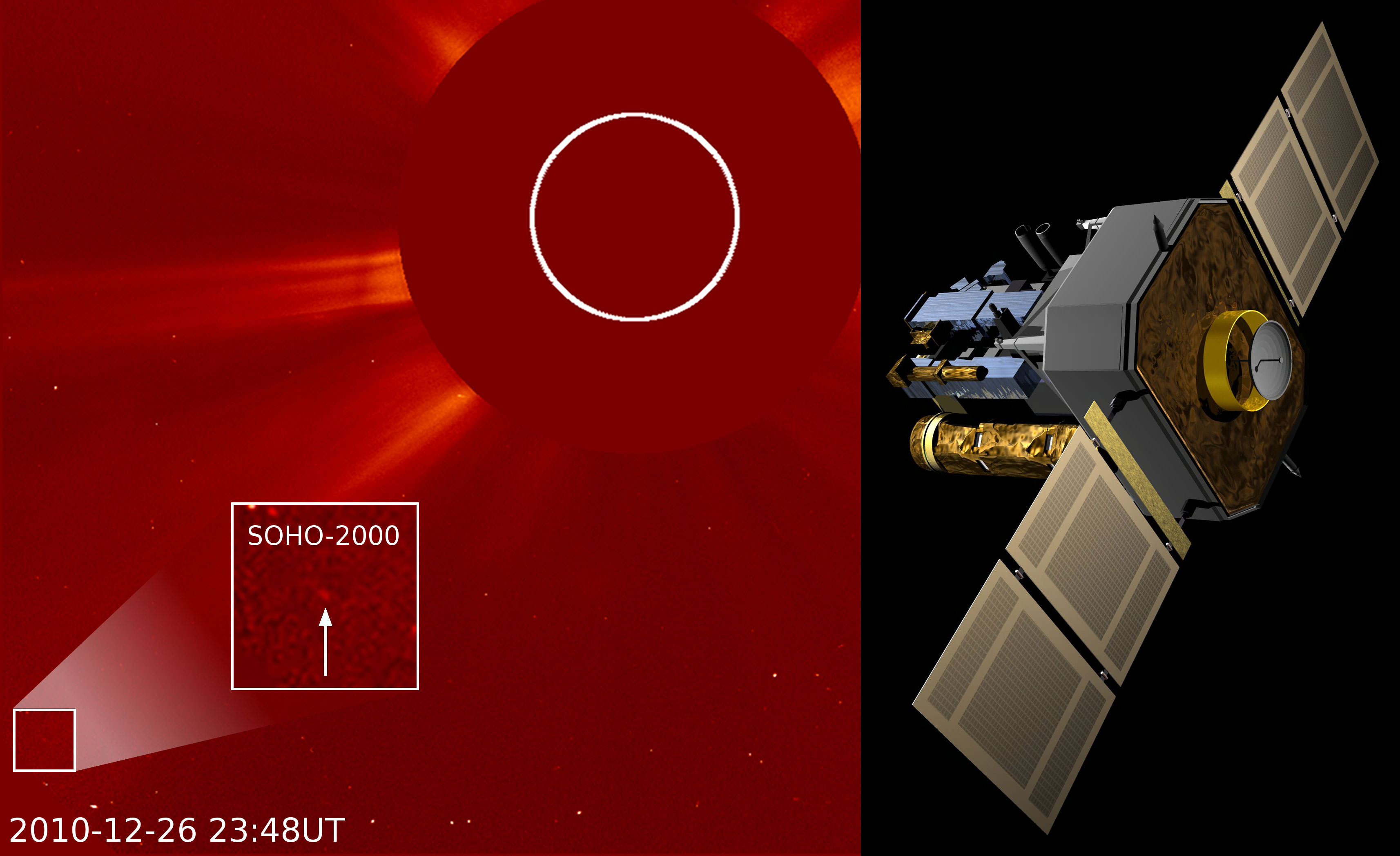

The repurposed Stardust spacecraft that flew past comet Wild 2 and brought back samples has just enough fuel to carry out maneuvers for the upcoming Tempel 1 flyby.

Larson said the preparations in designing the flyby sequences and software are almost complete and are being tested, and now the team is eagerly looking at the daily optical navigation images.

“We’re tracking where the comet is relative to the spacecraft,” he said, “and that will feed into our trajectory correction maneuvers. We have three more of those left before we arrive at the comet, and those will be used to target the spacecraft to the desired flyby point.”

The TCMs will occur on January 31, February 7, and then the last fully designed TCM will occur on February 12, two days before arrival.

There are challenges to using a recycled spacecraft.

“The primary challenge is, first of all, designing a new mission that it can accomplish with the fuel that it has left,” Larson said. “And through some clever mission design using some carefully timed trajectory correction maneuvers and taking advantage of some Earth gravity assists, we were able to modify the trajectory of the spacecraft to get it close to Tempel 1. So that’s been the primary challenge, and along with that is conserving the fuel that we have on board and making sure that we have enough fuel left to finish off this mission. Beyond that, there have been a few challenges in terms of aging equipment on board the spacecraft, — the spacecraft will be 12 years old in early February, and it’s well beyond its design life. And although everything is generally healthy on board, we have had a couple of pieces of equipment that were starting to age, and starting to degrade slightly. So we switched over to backup equipment so we were on fresh, healthy equipment, and we still have functioning equipment as backups.”

The closest approach will occur at 8:30 pm Pacific Time on February 14, 2011, where the spacecraft will be about 200 kilometers (125 miles) away from the surface of the comet, which is the closest any spacecraft has been to the surface of a comet.