[/caption]

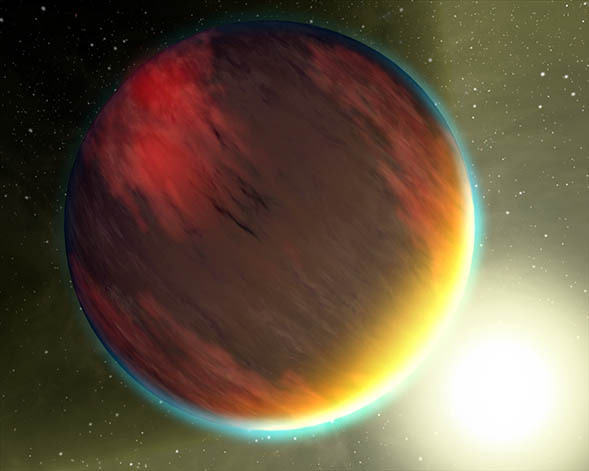

The basic chemistry for life has been detected the atmosphere of a second hot gas planet, HD 209458b. Data from the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes provided spectral observations that revealed molecules of carbon dioxide, methane and water vapor in the planet’s atmosphere. The Jupiter-sized planet – which occupies a tight, 3.5-day orbit around a sun-like star — is not habitable but it has the same chemistry that, if found around a rocky planet in the future, could indicate the presence of life. Astronomers are excited about the detection, as it shows the potential of being able to characterize planets where life could exist.

HD 209458b is in the constellation Pegasus.

“It’s the second planet outside our solar system in which water, methane and carbon dioxide have been found, which are potentially important for biological processes in habitable planets,” said researcher Mark Swain of JPL. “Detecting organic compounds in two exoplanets now raises the possibility that it will become commonplace to find planets with molecules that may be tied to life.”

Over a year ago, astronomers detected these same organic molecules in the atmosphere of another hot, giant planet, called HD 189733b, using the same two space telescopes. Astronomers can now begin comparing the chemistry and dynamics of these two planets, and search for similar measurements of other candidate exoplanets.

The detections were made through spectroscopy, which splits light into its components to reveal the distinctive spectral signatures of different chemicals. Data from Hubble’s near-infrared camera and multi-object spectrometer revealed the presence of the molecules, and data from Spitzer’s photometer and infrared spectrometer measured their amounts.

“This demonstrates that we can detect the molecules that matter for life processes,” said Swain. Astronomers can now begin comparing the two planetary atmospheres for differences and similarities. For example, the relative amounts of water and carbon dioxide in the two planets is similar, but HD 209458b shows a greater abundance of methane than HD 189733b. “The high methane abundance is telling us something,” said Swain. “It could mean there was something special about the formation of this planet.”

Rocky worlds are expected to be found by NASA’s Kepler mission, which launched earlier this year, but astronomers believe we are a decade or so away from being able to detect any chemical signs of life on such a body.

If and when such Earth-like planets are found in the future, “the detection of organic compounds will not necessarily mean there’s life on a planet, because there are other ways to generate such molecules,” Swain said. “If we detect organic chemicals on a rocky, Earth-like planet, we will want to understand enough about the planet to rule out non-life processes that could have led to those chemicals being there.”

“These objects are too far away to send probes to, so the only way we’re ever going to learn anything about them is to point telescopes at them. Spectroscopy provides a powerful tool to determine their chemistry and dynamics.”

For more information about exoplanets and NASA’s planet-finding program, check out PlanetQuest.

Source: Spitzer

CO2 and H2O are not organic molecules and CH4 is not usually considered such.

Over a hundred years ago chemists believed that organic molecules could only be formed by living things and considered NH3 to be the simplest molecule. Now we know that much more complex molecules are formed by non-living processes and exist throughout space.

Hate to be another Captain Obvious, but both CO2 and CH4 are considered organic. You could further classify CH4 as a hydro-carbon. It tends to always come down to that good ole ‘carbon’ atom. We’ll leave it just that simple.

I’d rather agree with Dale on this one. Methane is certainly the simplest alcane, and as such has one foot in organics, CO2 can’t boast that.

You can make actual organic molecules (lets say, C2 upwards) from methane rather easily, but it takes a highly complex path (photosynthesis) to do that from CO2.

However, the actual issue is not where to draw a frontier which will always be arbitrary. It’s rather that (once again) someone felt compelled to embellish their scientific work with some hype.

They might have very good (bad) reasons to do so, but we don’t really have to foster that trend here, do we?

All these planets are getting confusing. Where are the latest 32 located? Anyone know or haven’t they put this out yet?

Hi uncledan.

The original Press release (19th Oct) can be found by searching HARPS – ESO. Then look under “for the Public”.

The whole HARPS web site is very informatative however if you find the answer to your very practical question could you please add the answer to these posts!

Thanks for the response Brian, I checked all the press releases I could find, no mention of where the planets are. I even had tried JPL Planetquest and the ‘Public’ part of the ESO Harps site. I am figuring they haven’t released them yet and will have them out soon. There’s word that there are more planets to come in the next few months from this same survey.

Basically, I’m just interested to see where the planets are.

@uncledan:

I’m also interested to find out where this latest group are located. If you discover an article or link, please post it here. This is my favorite aspect of astronomy(other than Titan)

Thanks.

If we do find a “habitable” planet, we should send them EM Transmissions.

After the requisite prime numbers… Bach… and whatever, I suggest we start an insterstellar IM conversation:

“hihi, 400k/human being/earth). a/s/l?” (age, species, location)

The four-year delay or whatever shouldn’t be too annoying. ^^